Burger (pronounced bur-ger or bur-gha)

(1) A clipping of hamburger.

(2) A disc-shaped food patty (or patty on a bun), sometimes

containing ingredients other than beef including vegetarian concoctions.

(3) In Pakistani slang (usually derogatory), as burger or

hamburger, a stereotypically well-off Pakistani aspiring to a westernized

lifestyle.

(4) In Internet slang (apparently beginning on 4chan), an

American (as in a white, US citizen); of or relating to Americans.

(5) In computer graphical user interfaces (GUIs), as hamburger

button, an icon with three horizontal lines (the resemblance being to the

stacked ingredients of a burger). The

hamburger label was applied retrospectively, the original idea being to

represent a list, the icon’s purpose being to open up a list of options; it’s

thus also known as the “collapsed menu icon”.

1939: An invention of US English, extracted from hamburger

by misunderstanding (ham + burger). Use

of the noun hamburger is not exclusive to fast food. As early as 1616 it was noted as being the

standard description both of someone “a native of the city of Hamburg" and

also of ships “registered with Hamburg as their home port"). From 1838 it was the name of a black grape

indigenous to Tyrolia and after 1857, a variety of hen. Technically the meat product is a specific

variation of shaped, ground beef (minced meat); as a meatball is a sphere and

meatloaf is a rectangular cuboid, hamburgers (and burgers) are discs. Burger, burgeria & burgery are nouns; the noun plural is burgers.

Not that the burger is even exclusively fast food. Some very expensive burgers have been created

although, compared to their availability, there’s considerably less publicity about

their sales. As pieces of conspicuous

consumption they must have a niche but Netherlands diner De Daltons‘ (Hoofdstraat

151, 3781AD, Voorthuizen) opted to couple indulgence with a good cause, the

proceeds of their Golden Boy burger donated

to the local food bank. Emphasizing

quality rather than sheer bulk, the Golden

Boy was actually a good deal less hefty than some of the huge constructions

burger chains in the US have offered to satisfy the gulosity of some (burgers

with names like Heart Attack, XXXL, 55 oz

Challenge, One Pound of Elk, Sky-high Scrum, Monster Thickburger & Killer hardly subtle hints at the target

market).

By comparison, the price tag of €5,000 (US$5,100)

aside, the Golden Boy seems almost

restrained, though hardly modest, presented on a platter of whiskey-infused

smoke, its ingredients including Wagyu beef, king crab, beluga caviar, vintage

Iberico Jamon, smoked duck egg mayo, white truffle, Kopi Luwak coffee BBQ

sauce, pickled tiger tomato in Japanese matcha tea, all assembled on two Dom

Perignon infused gold-coated buns. The

chef insists it still just a burger and should be eaten using the hands, a nice

touch being that because the buns are covered in gold leaf, fingers will be

golden-tinted when the meal is finished.

A Golden Boy must be ordered two weeks in advance and a deposit of €750 (US$765)

is required.

People around the world had no doubt for centuries been

creating meatloaves, meatballs and meat patties before they gained the names

associated with them in Western cuisine.

The idea is simply to grind-up leftover or otherwise unusable cuts, add diced

vegetables & spices to taste and then blend with a thickening agent (flour,

breadcrumbs, eggs etc) to permit the mix to be rendered into whatever shape

is desired. The hamburger is no more an

invention of American commerce that the sandwich was of the English aristocracy.

The words however certainly

belong to late-stage capitalism. Hamburger

is noted in the US as describing meat patties in the late nineteenth century

(initially as hamburg steak), the connection apparently associative with German

immigrants for whom the port of embarkation was often Hamburg although there is

also a documented reference from 1809 in Iceland which referred to “meat smoked

in the chimney” as Hamburg beef. There are a dozen or more stories which

speculate on the origin of the modern hamburger but, in the nature of such an

ephemeral craft, there is little extant evidence of the early product and there’s

no reason not to assume something so obvious wasn’t “invented” in many places

at much the same time. The earliest

known references which track the progression seem to be hamburger sandwich

(1902), hamburger (1909) & burger (1939) although burger was by then an element

in its own right, acting as a suffix for the cheeseburger (1938). The culinary variations are legion: baconburger;

cheeseburger; fishburger; beefburger; bacon & egg burger; whale burger, dog

burger & dolphin burger (those three still a thing in parts of the Far East

although not now widely publicized); vege burger; vegan burger; kangaroo

burger, camel burger & crocodile burger (the Australians have a surplus of

all these fine forms of animal protein), lamb burger, steakburger, soyburger,

porkburger etc. Opportunistic constructions like burgerlicious are created as required. The homophones are Berger

& burgher (in English use a middle-class or bourgeois person). The noun plural is burgers.

Blogger Dario D had noticed that visually, the Big Macs he bought from random McDonalds outlets didn’t quite live up to the advertising. That’s probably true of much industrially produced food but what was intriguing was what was revealed when he applied a tape measure to his research. It seems Big Macs can’t be made exactly like they look in the advertising because then they would be too big to fit in the packaging.

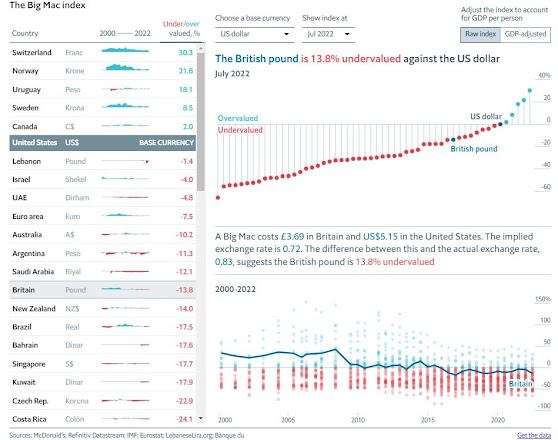

The Big Mac Index (BMI) was created by The Economist newspaper in 1986 and that the abbreviation is the same as for "body mass index" is presumed coincidental although the publication's caption writers often display some linguistic flair so who knows? The currency-related BMI is a price index which provides an indicative measure of purchasing power parity (PPP) between currencies and uses movements in the burger's price to suggest whether an official exchange rate is over or under-valued. The newspaper has never claimed the BMI is an authoritative economic tool and has always documented its limitations but many economists have found it interesting, not so much the result on any given day but as a trend which can be charted against other metrics. It was an imaginative approach, taking a single, almost standardized commodity available in dozens of countries and indexing the price, something which should in each place be most influenced by local factors including input costs (ingredients & labour), regulatory compliance, corruption and marketing. Even those who don’t agree it has much utility as an economic tool agree it’s fun and other have published variations on the theme, using either a product made in one place and shipped afar or one made with locally assembled, imported components.

The BMI also brought to wider attention the odd quirk. Although its place in the lineup has been replaced by a chicken-based dish, the Big Mac used to be on the McDonald's menu in India although, in deference to Hindu sensitivities (and in some states actual proscription), it was made not with beef but with lamb; it's said to taste exactly the same which seems a reasonable achievement. Burgers can be thematic and these are based on the seven wonders of the ancient world:

The Colossus of Rhodes (that’s a big burger with Greek

lamb)

The Great Pyramid of Giza (has an Egyptian sauce)

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon (vegetarian (lettuce

hanging out of it))

The Lighthouse of Alexandria (a lighter (low calorie) burger)

The Mausoleum at Halicarnassus (a traditional, very high calorie

burger)

The Statue of Zeus at Olympia (has a very hot

sauce)

The Temple of Artemis (Diana) at Ephesus (made with square or

rectangular bun and finished with burnt edges)

Lindsay Lohan with burger.