Zephyr (pronounced zef-uhr (U) or zef-er (non-U))

(1) A

gentle, mild breeze, considered the most pleasant of winds.

(2) By extension, any of various things of fine, light quality (fabric, yarn etc), most often applied to wool.

(3) In the mythology of Antiquity, the usual (Westernised) spelling of Ζεφυρος (Zéphuros or Zéphyros), the Greek and Roman god of the west wind, son of Eos & Astraeus and brother of Boreas; the Roman name was Zephyrus, Favonius.

(4) As a literary device, the west wind personified which should be used with an initial capital letter.

(5) In the mythology of Antiquity, as Zephyrette, a daughter of Aeolus; a tiny female spirit of the wind.

(6) A model name used on cars of variable distinction produced by the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo) and sold under the Ford, Mercury & Lincoln brands.

(7) A type of soft confectionery made by whipping fruit and berry purée (mostly apple purée) with sugar and egg whites, to which is added a gelling agent such as pectin, carrageenan, agar, or gelatine. Often called zefir, the use was a semantic loan from the Russian зефи́р (zefír).

Circa

1350: From the Middle English zeferus

& zephirus, from the Old English zefferus, from the Latin zephyrus, from the

Ancient Greek Ζέφυρος (Zéphuros or Zéphyros) (the west wind), probably from

the Greek root zophos (the west, the

dark region, darkness, gloom). The Latin

Zephyrus was the source also of zéphire

(French), zefiro (Spanish) and zeffiro (Italian). The feminine form zephyrette (capitalised and not) is rare and the

alternative spellings were zephir

& zefir, the latter (in the context of food) still current. The casual use in meteorology dates from

circa 1600 and the meaning has shifted from the classical (something warm, mild and occidental) to now be any gentle breeze or waft where the wish is to suggest a wind not strong and certainly not a gust, gale, cyclone, blast, typhoon or tempest. Zephyr is a noun & verb, zephyred is a verb & adjective, zephyring is a verb and zephyrous, zephyrlike & zephyrean are adjectives; the noun plural is zephyrs. The adverb zephyrously is non-standard.

In Greek mythology, Ζεφυρος (transliterated as Zéphuros

or Zéphyros) was the god of the west wind, one of the four seasonal Anemoi (wind-gods),

the others being his brothers Notus (god of the south wind), Eurus (god of the

east wind) and Boreas (god of the east wind). The Greek myths offer many variations of the life

of Zephyrus, the offspring of Astraeus & Eos in some versions and of Gaia

in other stories while there were many wives, depending on the story in which

he was featured. Despite that, he’s also

sometimes referred to as the “god of the gay”, based on the famous tale of Zephyrus

& Hyakinthos (Hyacinthus or Hyacinth).

Hyacinth was a Spartan youth, an alluring prince renowned for his beauty

and athleticism and he caught the eye of both of both Zephyrus and Apollo (the god

of sun and light) and the two competed fiercely for the boy’s affections. It was Apollo whose charms proved more

attractive which left Zephyrus devastated and in despair. One day, Zephyrus chanced upon the sight of Apollo

and Hyacinth in a meadow, throwing a discus and, blind with anger, sent a great

gust of wind at the happy couple, causing the discus to strike Hyacinth

forcefully in the head, inflicting a mortal injury. Stricken with grief, as Hyacinth lay dying in

his arms, Apollo transformed the blood trickling to the soil into the hyacinth

(larkspur), flower which would forever bloom in memory of his lost, beautiful

boy. Enraged, Apollo sought vengeance but Zephyrus was protected by Eros, the god

of love, on what seems the rather technical legal point of the intervention of

Zephyrus being an act of love. There was

however a price to be paid for this protection, Zephyrus now pledged to serve

Eros for eternity and the indebted god of the west wind soon received his first

task. There are other tales of how Cupid and Psyche came to marry but in this one, with uncharacteristic clumsiness, Cupid

accidently shot himself with one of his own arrows of love while gazing upon

the nymph Psyche and it was Zephyrus who kidnapped her, delivering his abducted

prize to Cupid to be his bride.

Zephyros was in classical art most often depicted as a handsome, winged youth and a large number of surviving Greek vases are painted with unlabeled figures of a winged god embracing a youth and these are usually identified as Zephyros and Hyakinthos although, some historians detecting detail differences list a number of them as being of Eros (the god of Love) with a symbolic youth. Although sometimes rendered as a winged god clothed in a green robe and crowned with a wreath of flowers, in Greco-Roman mosaics, Zephyros appears usually in the guise of spring personified, carrying a basket of unripened fruit. In some stories, he is reported to be the husband of Iris, the goddess of the rainbow and Hera’s messenger and in others, Podarge the harpy (also known as Celano) is mentioned as the wife of Zephyrus but in most of the myths he was married to Chloris. Chloris by most accounts was an Oceanid nymph and in the tradition of Boreas & Orithyia and Cupid and Psyche, Zephyrus made Chloris his wife by abduction, making her the goddess of flowers, for she was the Greek equivalent of Flora and, living with her husband, enjoyed a life of perpetual spring.

Standardized wind: The Beaufort wind force scale

With strategically placed palms, Lindsay Lohan resists a zephyr's efforts to induce a wardrobe malfunction, MTV Movie Awards, Los Angeles, 2008 (left) which may be C&Ced (compared & contrasted) with the stronger breeze (probably 3-4 on the Beaufort Scale) disrupting the modern art installation that is Donald Trump's (b 1946; US president 2017-2021 and since 2025) hair (right).

The Beaufort wind force scale was devised because the British Admiralty was accumulating much data about prevailing weather conditions at spots around the planet where the Royal Navy sailed and it was noticed there was some variation in way different observers would describe the wind conditions. In the age of sail, wind strength frequency and direction was critical to commerce and warfare and indeed survival so the navy needed to information to be as accurate an consistent as possible but in the pre-electronic age the data came from human observation, even mechanical devices not usually in use. What Royal Navy Captain (later Rear Admiral) Sir Francis Beaufort 1774–1857) early in nineteenth century noticed was that a sailor brought up in a blustery place like the Scottish highlands was apt to understate the strength of winds while those from calmer places were more impressed by even a moderate breeze, little more than what a hardy Scots sold salt would call a zephyr. Accordingly, he developed a scale which was refined until formally adopted by the Admiralty during the 1930s after he’d been appointed Hydrographer of the Navy. The initial draft reflected the functional purpose, the lowest rating describing the sort of gentle zephyr which was just enough to enable a ship's captain slowly to manoeuvre while the highest was of the gale-force winds which would shred the sails. As sails gave way to steam, the scale was further refined by referencing the effect of wind upon the sea rather than sails and it was adopted also by those working in shore-based meteorological stations. In recent years, categories up to 17 have been added to describe the phenomena described variously as hurricanes, typhoons & cyclones.

In the mythology of Antiquity, Zephyrette was a daughter of Aeolus and a tiny female spirit of the wind. That the nymph's name was early in the twentieth century appropriated by the National Biscuit Company (1898–1971, Nabisco (1971–1985) & RJR Nabisco (1985–1999) and now a subsidiary of Mondelēz International) to describe a light, crisp cracker, recommended to be used for hors d'oeuvres might outrage feminists studying denotation and connotation in structural linguistics and the more they delve, the greater will be the outrage. Mostly, the word "zephyr" now is used by novelists and poets because while indicative of the force of a wind, it's not defined and is thus not a formal measure so what's a zephyr in one poem might be something more or less in another. In other texts, such inconsistencies might be a problem but for the few thousand souls on the planet who still read poetry, it's all part of the charm.

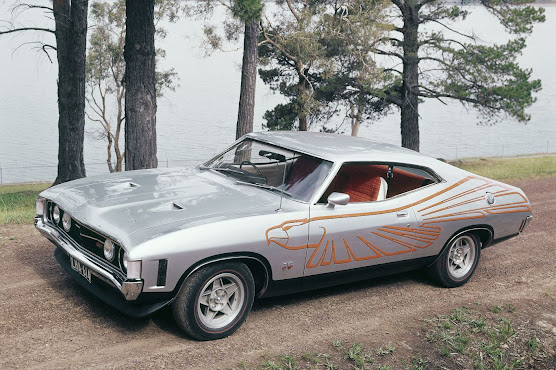

For good & bad: FoMoCo's Zephyrs

In the inter-war era, the finest of

the big American cars, the Cadillacs, Lincolns, Packards and Duesenbergs, offered

craftsmanship the equal of anything made in Europe and engineering which was

often more innovative. The 1930s however

were difficult times and by mid-decade, sales of the big K-Series Lincolns, the

KA (385 cubic inch (6.3 litre) V8) and KB (448 cubic inch (6.3 litre) V12) were

falling. Ford responded by designing a smaller,

lighter Lincoln range to bridge the gap between the most expensive Ford and the

lower-priced K-Series Lincolns, the intention originally to power it with an

enlarged version of the familiar Ford V8 but family scion Edsel Ford

(1893–1943; president of the Ford Motor Company (FoMoCo), 1919-1943), decided instead to

develop a V12, wanting both a point of differentiation and a link to K-Series

which had gained for Lincoln a formidable reputation for power and durability. Develop may however be the wrong word, the

new engine really a reconfiguration of the familiar Ford V8, the advantage in that

approach being it was cheaper than an entirely new engine, the drawback the

compromises and flaws of the existing unit were carries over and in some aspects,

due to the larger size and greater internal friction, exaggerated.

The V12 however was not just V8 with four additional pistons, the block cast with a vee-angle of 75o rather than the eight’s 90o, a compromise between compactness and the space required for a central intake manifold and the unusual porting arrangement for the exhaust gases. The ideal configuration for a V12 is 60o and without staggered throws on the crankshaft, the 75o angle yielded uneven firing impulses, although, being a relatively slow and low-revving unit, the engine was felt acceptably smooth. The cylinder banks used the traditional staggered arrangement, permitting the con-rods to ride side-by-side on the crank and retained the Ford V-8’s 3.75 inch (90.7 mm) stroke but used a small bore of just 2.75 inches (69.75 mm), then the smallest of any American car then in production, yielding a displacement of 267 cubic inches (4.4 litres), a lower capacity than many of the straight-eights and V8s then on the market.

Because the exhaust system was routed through the block to four ports on each side of the engine, cooling was from the beginning the problem it had been on the Ford V8 but on a larger scale. Although the cooling system had an apparently impressive six (US) gallon (22.7 litre) capacity, it quickly became clear this could, under certain conditions, be marginal and the radiator grill was soon extended to increase airflow. Nor was lubrication initially satisfactory, the original oil pump found to be unable to maintain pressure when wear developed on the curfaces of the many bearings; it was replaced with one that could move an additional gallon (3.79 litre) a minute. Most problems were resolved during the first year of production and the market responded to the cylinder count, competitive price and styling; after struggling to sell not even 4000 of the big KAs in 1935, Lincoln produced nearly 18,000 Zephyrs in 1936, sales growing to over 25,000 the following year. Production between 1942-1946 would be interrupted by the war but by the time the last was built in 1948, by which time it had been enlarged to 292 cubic inches (4.8 litre (there was in 1946, briefly, a 306 cubic inch (5.0 litre) version) over 200,000 had been made, making it the most successful of the American V12s. It was an impressive number, more than matching the 161,583 Jaguar built over a quarter of a century (1971-1997) and only Daimler-Benz has made more, their count including both those used in Mercedes-Benz cars and the the DB-60x inverted V12 aero-engines famous for their wartime service with the Luftwaffe and the Mercedes-Benz T80, built for an assault in 1940 on the LSR (Land Speed Record). Unfortunately, other assaults staged by the Third Reich (1939-1945) meant the run never happened but the T80 is on permanent exhibition in the factory's museum in Stuttgart so viewers can ponder Herr Professor Ferdinand Porsche's (1875–1951) pre-war slide-rule calculations of a speed of 650 km/h (404 mph) (not the 750 km/h (466 mph) sometimes cited).

1939 Lincoln-Zephyr Three Window Coupe (Model Code H-72, 2500 of which were made out of the Zephyr’s 1939 production count of 21,000). It was listed as a six-seater but the configuration was untypical of the era, the front seat a bench with split backrests, allowing access to the rear where, unusually, there were two sideways-facing stools. In conjunction with the sloping roofline, it was less than ideal for adults and although the term “3+2” was never used, that’s probably the best description. The H-72 Three Window Coupe listed at US$1,320, the cheapest of the six variants in the 1939 Zephyr range.

It may sound strange that in a country still recovering from the Great Depression Ford would introduce a V12 but the famous “Flathead” Ford V8 was released in 1932 when economic conditions were at their worst; people still bought cars. The V12 was also different in that although a configuration today thought of as exotic or restricted to “top of the line” models, for Lincoln the Zephyr was a lower-priced, mid-size luxury car to bridge a gap in the corporate line-up. Nor was the V12 a “cost no object” project, the design using the Flathead’s principle elements and while inaccurate at the engineering level to suggest it was the “Ford V8 with four cylinders added” the concept was exactly that and if the schematics are placed side-by-side, the familial relationship is obvious. Introduced in November 1935 (as a 1936 model), the styling of the Lincoln Zephyr attracted more favourable comment than Chrysler’s Airflows (1934-1937), an earlier venture into advanced aerodynamics (then known as “streamlining”) and the name had been chosen to emphasize the wind-cheating qualities of the modernist look. With a raked windscreen and integrated fenders, it certainly looked slippery and tests in modern wind tunnels have confirmed it indeed had a lower CD (drag coefficient) than the Airflows which looked something like unfinished prototypes; the public never warmed to the Airflows, however accomplished the engineering was acknowledged to be. By contrast, the Zephyrs managed to cloak the functional efficiency in sleek lines with pleasing art deco touches; subsequently, New York’s MOMA (Museum of Modern Art) acknowledged it as “the first successfully streamlined car in America”. So much did the style and small V12 capture the headlines it was hardly remarked upon that with a unitary body, the Zephyr was the first Ford-made passenger vehicle with an all-steel roof, the method of construction delivering the required strength at a lighter weight, something which enabled the use of an engine of relatively modest displacement.

In 1942, just after the US had entered the war (thereby legitimizing the term “World War II” (1939-1945)) the expatriate (the apocope “expat” not in general use until the 1950s when Graham Greene's (1904-1991) novel The Quiet American (1955) appears to have given it a boost) UK-born US journalist Alistair Cooke began a trip taking from Washington DC and back, via Virginia, Florida, Texas, California, Washington state and 26 other states, purchasing for the project a 1936 Lincoln Zephyr V12, his other vital accessories five re-tread tyres (with the Japanese occupation of Malaya, rubber was in short supply and tyres hard to find), a gas (petrol) ration coupon book and credentials from his employer, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation). It was a journalist’s project to “discover” how the onset of war had changed the lives of non-combatant Americans “on the home front” and his observations would provide him a resource for reporting for years to come. Taking photographs on his travels, he’d always planned to use the material for a book but, as a working journalist during the biggest event in history, it was always something done “on the side” and by the time he’d completed a final draft it was 1945 and with the war nearly over, he abandoned the project, assuming the moment for publication had passed. It wasn’t until two years after his death that The American Home Front 1941-1942 (2006) was released, the boxed manuscript having been unearthed in the back of a closet, under a pile of his old papers.

Cooke had a journalist’s eye and the text was interesting as a collection of unedited observations of the nation’s culture, written in the language of the time. In the introduction Cooke stated: “I wanted to see what the war had done to the people, to the towns I might go through, to some jobs and crops, to stretches of landscape I loved and had seen at peace; and to let the significance fall where it might.” During his journey, he interviewed many of the “ordinary Americans” then traditionally neglected by history (except when dealt with en masse), not avoiding contentious issues such as anti-Semitism and racism but also painted word-pictures of the country through which he was passing, never neglecting to describe the natural environment, most of it unfamiliar to an Englishman who’d spent most of his time in the US in cities on the east and west coasts. As a footnote, although the Zephyr’s V12 engine has always been notorious for the deficiencies in its cooling system, at no time during the journey did Cooke note the car overheating so either the radiator and plumbing did the job or he thought the occasional boil-over so unremarkable he made no remark.

%201967%20Ad.jpg)