Decapitate (pronounced dih-kap-i-teyt)

(1) To cut off the head; to behead.

(2) Figuratively, to oust or destroy the leadership or

ruling body of a government, military formation, criminal organization etc.

1605–1615: From the fourteenth century French décapiter,

from the Late Latin dēcapitātus, past

participle of dēcapitāre, the

construct being dē- + capit- (stem of caput (head), genitive capitis), from the Proto-Italic kaput, from the

Proto-Indo-European káput- (head) + -ātus.

The Latin prefix

dē- (off) was from the preposition dē (of, from); the Old English æf- was a similar prefix. The Latin suffix -ātus was from the Proto-Italic -ātos,

from the primitive Indo-European -ehtos. It’s regarded as a

"pseudo-participle" and perhaps related to –tus although though similar formations in other Indo-European

languages indicate it was distinct from it already in early Indo-European

times. It was cognate with the

Proto-Slavic –atъ and the

Proto-Germanic -ōdaz (the English

form being -ed (having). The feminine

form was –āta, the neuter –ātum and it was used to form adjectives

from nouns indicating the possession of a thing or a quality. The English suffix -ate was a word-forming

element used in forming nouns from Latin words ending in -ātus, -āta, & -ātum

(such as estate, primate & senate).

Those that came to English via French often began with -at, but an -e

was added in the fifteenth century or later to indicate the long vowel. It can also mark adjectives formed from Latin

perfect passive participle suffixes of first conjugation verbs -ātus, -āta, & -ātum (such as desolate, moderate & separate). Again, often they were adopted in Middle

English with an –at suffix, the -e appended after circa 1400; a doublet of –ee. Decapitate, decapitated

& decapitating are verbs, decapitation & decapitator are nouns; the common noun plural is decapitations.

As a military strategy, the idea of decapitation is as old as warfare and based on the effective “cut the head off the snake”. The technique of decapitation is to identify the leadership (command and control) of whatever structure or formation is hostile and focus available resources on that target. Once the leadership has been eliminated, the effectiveness of the rest of the structure should be reduced and the idea is applied also in cyber warfare although in that field, target identification can be more difficult. The military’s decapitation strategy is used by many included law enforcement bodies and can to some extent be applied in just about any form of interaction which involves conflicting interests. The common English synonym is behead and that word may seem strange because it means “to take off the head” where the English word bejewel means “to put on the jewels”. It’s because of the strange and shifting prefix "be-". Behead was from the Middle English beheden, bihefden & biheveden, from the Old English behēafdian (to behead). The prefix be- however evolved from its use in Old English. In modern use it’s from the Middle English be- & bi-, from the Old English be- (off, away), from the Proto-Germanic bi- (be-), from the Proto-Germanic bi (near, by), the ultimate root the primitive Indo-European hepi (at, near) and cognate be- in the Saterland Frisian, the West Frisian, the Dutch, the German & Low German and the Swedish. When the ancestors of behead were formed, the prefix be- was appended to create the sense of “off; away” but over the centuries it’s also invested the meanings “around; about” (eg bestir), “about, regarding, concerning” (eg bemoan), “on, upon, at, to, in contact with something” (eg behold), “as an intensifier” (eg besotted), “forming verbs derived from nouns or adjectives, usually with the sense of "to make, become, or cause to be" (eg befriend) & "adorned with something" (eg bejewel)).

A less common synonym is decollate, from the Latin decollare (to behead) and there’s also

the curious adjective decapitable which (literally “able or fit to be

decapitated”) presumably is entirely synonymous with “someone whose head has

not been cut off” though not actually with someone alive, some corpses during

the French Revolution being carted off to be guillotined, the symbolism of the seemingly

superfluous apparently said to have been greeted by the mob "with a cheer".

1971 Citroën DS21 Décapotable Usine with non-standard interior including bespoke headrests in the style used on some Jensen Interceptors.

Produced between 1955-1975, the sleek Citroën DS must have seemed something from science fiction to those accustomed to what was plying the roads outside but although it soon came to be regarded as something quintessentially French, the DS was actually designed by an Italian. In this it was similar to French fries (invented in Belgium) and Nicolas Sarközy (b 1955; President of France 2007-2012), who first appeared on the planet the same year as the shapely DS and he was actually from here and there. It was offered as the DS and the lower priced ID, the names a play on words, DS in French pronounced déesse (goddess) and ID idée (idea). The goddess nickname caught on though idea never did, presumably because visually the two were so similar with differences limited mostly to the ID's simplified mechanical specification.

Henri Chapron had attended the Paris Auto

Salon when the DS made its debut and while Citroën had planned to offer a

cabriolet, little had been done beyond some conceptual drawings and development

resources were instead devoted to higher-volume variants, the ID (a less

powerful DS with simplified mechanicals and less elaborate interior

appointments) which would be released in 1957 and the Break (a station wagon

marketed variously the Safari, Break, Familiale or Wagon), announced the next

year. Chapron claims it took him only a

glance at the DS in display for him instantly to visualise the form his

cabriolet would take but creating one proved difficult because such was the

demand Citroën declined to supply a partially complete platform, compelling the

coach-builder to secure a complete car from a dealer willing (on an undisclosed

basis) to “bump” his name up the waiting list while he worked on the blueprints.

The DS and ID are well documented in the model's history but there was also the more obscure DW, built at Citroën's UK manufacturing plant in the Berkshire town Slough which sits in the Thames Valley, some 20 miles west of London. The facility was opened in February 1926 as part of the Slough Trading Estate (created just after World War I (1914-1918)) which was an early example of an industrial park, the place having the advantage of having the required infrastructure because it had been constructed by the government for wartime production and maintenance activities. Citroën was one of the first companies to establish an operation on the site, overseas assembly prompted by the UK government's imposition of tariffs (33.3% on imported vehicles, excluding commercial vehicles) and the move had the added advantage of the right-hand-drive (RHD) cars being able to be exported throughout the British Empire under the “Commonwealth Preference”, arrangements (a low-tariff scheme), elements of which would endure as a final relic of the chimera of imperial free trade until 1973 when the UK joined the EEC (the multi-national European Economic Community, a "common market" which would expand (in numbers and scope) to become the modern EU (European Union) which continues to exist in a twilight zone between a Zollverein and a confederation). Despite the end of Commonwealth preferences however, the Australian outposts of Chrysler (until 1976) and Ford (until 1984) continued to supply a trickle of what were by UK standards large sedans and station wagons. Then standard-size family cars in Australia (and compacts in the US), offering much space and usually fitted with torquey V8 engines, they found a some popularity among those towing things like horse floats.

Slough's contribution to footnotes in Citroën's history: The Bijou (1959-1964, left) and the 2CV (1948-1990, right) on which it was based. The 2CV designation meant deux chevaux (literally "two horses"), a reference to "two taxable horsepower (HP)") although the output of most varied between 12-28 (net) HP which was modest but the 2CV proved a remarkably capable machine and between 1958-1971 the factory built 694 4WD (four-wheel-drive) "Sahara" variants, the configuration achieved with two engines and gearboxes, the rear-mounted unit driving the rear wheels. It remains one of the most commercially successful twin-engined cars.

Beginning with the Type A in 1926 and ending with a final DS in 1965, some 57,000 Citroëns were assembled at Slough including the Type C, ‘6’, ‘10’, and ‘Big Twelve’ (all, like the Type A, being RWD (rear-wheel-drive) and four & six cylinder versions of the FWD (front-wheel-drive) Traction Avant. On a smaller scale, there were runs also of the 2CV, a 2CV pick-up truck the Admiralty ordered for use in ports and, most bizarrely, the fiberglass bodied, 2CV-based Bijou which was unique to the UK. The Bijou was an attempt to make the 2CV more acceptable to British tastes by replacing the distinctive, utilitarian coachwork of the original with something more contemporary. It was essentially the same approach Volkswagen would take with its Type 3 & Type 4 (the 411/412) which used the familiar Type 1 (Beetle) underpinnings beneath what was then closer to mainstream styling. While the Type 3 was a success, the Type 4 floundered and British consumers never much took to the little Bijou, barely 200 sold in half a decade of production. The Slough ID, DW & DS variants differed in detail from the French-built cars, featuring 12-volt Lucas electrics, smaller diameter headlights, ribbed metal flashings for the B & C pillars, a black-painted front apron, chromed brass cornets with protruding Lucas indicators and a different front bumper bar, necessitated by local laws specifying how licence plates were to be mounted. Being England in the 1960s, there were also more chrome-plated fittings with slightly different lights used at the rear. Interestingly, given the class-consciousness of the era, externally, a DW was indistinguishable from the more expensive DS and both differed from the French versions in that all three ashtrays (one in the front and two in the front seat-backs) were large enough to accommodate a pipe (the engineers reputedly testing the devices with their own Stanwells and Dunhills).

Unlike similar operations, which in decades to come would appear world-wide, the Slough Citroëns were not assembled from CKD (completely knocked down) kits which needed only local labor to bolt them together but used a mix of imported parts and locally produced components. The import tariff was avoided if the “local content” (labor and domestically produced (although those sourced from elsewhere in the Commonwealth could qualify) parts) reached a certain threshold (measured by the total P&L (parts & labor) value in local currency); it was an approach many governments would follow and it remains popular today as a means of encouraging (and protecting) local industries and creating employment. People able to find jobs in places like Slough would have been pleased but for those whose background meant they were less concerned with something as tiresome as paid-employment, the noise and dirt of factories seemed just a scar upon the “green and pleasant land” of William Blake (1757–1827). In his poem Slough (1937), Sir John Betjeman (1906–1984; Poet Laureate 1972-1984), perhaps recalling Stanley Baldwin's (1867–1947; UK prime-minister 1923-1924, 1924-1929 & 1935-1937) “The bomber will always get through” speech (1932) welcomed the thought, writing: “Come friendly bombs and fall on Slough! It isn’t fit for humans now” Within half a decade, the Luftwaffe would grant his wish. Poets should be careful what they wish for although these days most seem to wish for little more than state subsidies and grants from literature boards, institutions anxious to ensure a slither of tax revenue is devoted to creating an over-supply where there's little demand.

During World War II (1939-1945), the Slough plant was requisitioned for military use and some 23,000 CMP (Canadian Military Pattern) trucks were built, civilian production resuming in 1946. After 1955, Slough built both the ID and DS, both with the traditional English leather trim and a wooden veneer dashboard appeared on the ID, a touch which some critics claimed was jarring among the otherwise modernist ambiance but the appeal was real because some French distributors imported and fitted the Slough dashboard parts for owners who liked the look. In 1964, a unique Slough-built DW was created fill the gap between the ID & DS, the DW using the DS's more powerful engine, power steering and braking system but fitted with a conventional manual clutch and gearbox. The timber veneers were not fitted as standard to the DWs but many survivors do feature them so either dealers at the time offered the option or the slabs have been retro-fitted and although the DW’s configuration may seem a curiosity, it must have been a “sweet spot” for the UK market because over the period its sales exceeded those of the ID & DS combined (DW19: 365, ID19: 135. DS19: 109). A niche within a niche, the DW remained in production only until September 1964 when the range gained the new 1,985 cm3 engine, marked by the designation changing to DS19 DL, only 22 of which left the line before the 2,175 cm3 DS21 was introduced and made available with both a manual gearbox and the hydraulic automatic. Outside of the UK, the DW was named DS19M, a moniker that rationally made more sense because the only notable difference between the DW and the DS was the fitment of a manual gearbox and foot-operated clutch. Citroën assembly in Slough ended in February 1965 and although the factory initially retained the plant as a marketing, service & distribution centre, in 1974 these operations were moved to other premises and the buildings were taken over by Mars Confectionery. Today, no trace remains of Citroën's presence in Slough.

1963 Citroën Le Dandy & 1964 Citroën Palm Beach by Carrosserie Chapron.

Citroën DS by Carrosserie Chapron production count 1958-1974.

Demand was higher at a lower price-point, as Citroën's 1325 cabriolets indicate but Carrosserie Chapron until 1974 maintained output of his more exclusive and expensive lines although by the late 1960s, output, never high, had slowed to a trickle. Chapron’s originals varied in detail and the most distinguishing difference between the flavors was in the rear coachwork, the more intricate being those with the "squared-off" (sometimes called "finned" or "fin-tailed") look, a trick Mercedes-Benz had in 1957 adopted to modernize the 300d (W189, 1957-1963, the so called "Adenauer Mercedes", named after Konrad Adenauer (1876–1967; chancellor of the FRG (Federal Republic of Germany (the old West Germany) 1949-1963) who used several of the W186 (300, 300b, 300c, 1951-1957) & 300s models as his official state cars). Almost all Chapron's customized DS models were built to special order between under the model names La Croisette, Le Paris, Le Caddy, Le Dandy, Concorde, Palm Beach, Le Léman, Majesty, & Lorraine; all together, 287 of these were delivered and reputedly, no two were exactly alike.

Citroën Concorde coupés by Chapron: 1962 DS 19 (left) and 1965 DS 21 (right). The DS 21 is one of six second series cars, distinguished by their “squared-off” rear wing treatment and includes almost all the luxury options Chapron had on their list including electric windows, leather trim, the Jaeger instrument cluster, a Radiomatic FM radio with automatic Hirschmann antenna, the Robergel wire wheel covers and the Marchal auxiliary headlights.

Alongside the higher-volume Cabriolets d'Usine, Carrosserie Chapron continued to produce much more expensive décapotables (the Le Caddy and Palm Beach cabriolets) as well as limousines (the Majesty) and coupés, the most numerous of the latter being Le Dandy, some 50 of which were completed between 1960-1968. More exclusive still was another variation of the coupé coachwork, the Concorde with a more spacious cabin notably for the greater headroom it afforded the rear passengers. Only 38 were built over five years and at the time they cost as much as the most expensive Cadillac 75 Limousine.

Bossaert's Citroën DS19-based GT 19 (1959-1964); the Marchal auxiliary headlights a later addition (top).

Others also built DS coupés & convertibles. Between 1959-1964 Belgium-born Hector Bossaert produced more than a dozen DS coupés and what distinguished his was a platform shortened by 470 mm (18½ inches) and the use of a notchback roof-line. Dubbed the Bossaert GT 19, the frontal styling was unchanged although curiously, the Citroën chevrons on the rear pillars were rotated by 90° (ie becoming directional arrows); apart from the GT 19 Bossaert script on the boot lid (trunk lid), they are the vehicle’s only external identification. Opinion remains divided about the aesthetes of the short wheelbase (SWB) DSs. While it’s conceded the Chapron coupés & cabriolets do, in terms of design theory, look “unnaturally” elongated, the lines somehow suit the machines and the word most often used is “elegant” whereas the SWB cars do seem stubby and obviously truncated although, had the originals never existed, perhaps the SWB would look more "natural". The consensus seems to be the GT 19 was the best implementation of the SWB idea, helped also by it being 70 mm (2¾ inches) lower than the donor DS and perhaps that would be expected given the design was by the Italian Pietro Frua (1913-1983). Bossaert also increased the power. Although the hydro-pneumatic suspension and slippery aerodynamics made the DS a fine high-speed cruiser, the 1.9 litre (117 cubic inch) four cylinder engine was ancient and inclined to be agricultural if pushed; acceleration was not sparking. Bossaert thus offered “tuning packages” which included the usual methods: bigger carburetors & valves, and more aggressive camshaft profile and a higher compression ratio, all of which transformed the performance from “mediocre” to “about average”.

The one-off Bossaert GT 19 convertible (left) and the one off 1966 Citroën DS21-based Bossaert cabriolet (right).

Demand was limited by the price; a GT 19 cost more than double that of a DS and the conversion was more than a Jaguar so one really had to be prepared to pay for the exclusivity. It was a common tale in the post-war years as coach-builders struggled to convince buyers to pay for their four-cylinder "specials" when larger, faster and more refined six or even eight cylinder vehicles were available from established manufacturers for so much less. Additionally, when the Citroën management discovered someone in a garage was “hotting-up” their engines, it was made clear that would invalidate any warranty. Most sources say only 13 were built but there were also two convertibles, one based on the GT 19 (though fitted with fared in headlights) and the other quite different, owing more to the Chapron Caddy; both remained one-offs. Two of the GT 19 coupés and the later convertible survive.

Right-side clignotant (left) on 1974 Citroën DS23 Pallas (right).

Retaining the roof did offer designers possibilities denied after decapitation. On the DS & ID saloons, the clignotants (turn indicators; flashers) were mounted in a housing which was styled to appear as a continuation of the roof-gutter; it was touches like that which were a hint the lines of the DS were from the drawing board of an Italian, Flaminio Bertoni (1903–1964) who, before working in industrial design in pre-war Italy, had trained as a sculptor. Citroën seems never to have claimed the placement was a safety feature and critics of automotive styling have concluded the flourish was added as part of the avant-garde vibe. However, the way the location enhanced their visibility attracted the interest of those advocating things needed to be done to make automobiles safer and while there were innovations in “active safety” (seat-belts, crumple zones etc), there was also the field of “passive safety” and that included visibility; at speed, reducing a driver’s reaction time by a fraction of a second can be the difference between life and death and researchers concluded having a “third brake light” at eye level did exactly that. So compelling was the case it was under the administration of Ronald Reagan (1911-2004; US president 1981-1989 and hardly friendly to new regulations) that in 1986 the US mandated the CHMSL (centre high mount stop lamp) but because the acronym lacked a effortless pronunciation the legislated term never caught on and the devices are known variously as “centre brake light”, “eye level brake light”, “third brake light”, “high-level brake light” & “safety brake light”. Unintentionally, Citroën may have started something though it took thirty years to realize the implications.

Coincidently, in the same year the DS debuted, Rudimentary seat-belts first appeared in production cars during the 1950s but the manufacturers must have thought the public indifferent because their few gestures were tentative such as in 1956 when Ford had offered (as an extra-cost option) a bundle of safety features called the “Lifeguard Design” package which included:

(1) Padded dashboards (to reduce head injuries).

(2) Recessed steering wheel hub (to minimize chest injuries).

(3) Seat belts (front lap belts only).

(4) Stronger door latches (preventing doors flying open in a crash).

(5) Shatter-resistant rear-view mirror (reducing injuries caused by shards of broken glass).

The standard features included (1) the Safety-Swivel Rear View Mirror, (2) the Deep-Center Steering Wheel with recessed post and bend-away spokes and (3) Double-Grip Door Latches with interlocking striker plate overlaps; Optional at additional cost were (4) Seat Belts (single kit, front or rear, color-keyed, nylon-rayon with quick one-handed adjust/release aluminium buckle) (US$5). There were also "bundles", always popular in Detroit. Safety Package A consisted of a Padded Instrument Panel & Padded Sun Visors (US$18) while Safety Package B added to that Front-Seat Lap Seat Belts (US$27). On the 1956 Thunderbird which used a significantly different interior design, the options were (1) the Lifeguard Padded Instrument Panel (US$22.65), (2) Lifeguard Padded Sun Visors (US$9) and (3) Lifeguard Seat Belts (US$14). Years later, internal documents would be discovered which revealed conflict within the corporation, the marketing department opposed to any mention of "safety features" because that reminded potential customers of car crashes; they would prefer they be reminded of new colors, higher power, sleek new lines and such. So, little was done to promote the “Lifeguard Design”, public demand was subdued and the soon the option quietly was deleted from the list.

The rising death-toll and complaints from the insurance industry however meant the issue of automotive safety re-surfaced in the 1960s and the publication by lawyer Ralph Nadar (b 1934) of the book Unsafe at Any Speed (1965) which explored the issue played a part in triggering what proved to be decades of legislation which not even the efforts and money of Detroit's lobbyists could stop although some delays in implementation were achieved and there was the odd victory (such as the survival of the convertible and ironically, that was a matter about which Detroit was at the time mostly indifferent). Among the delays achieved (albeit a minor and temporary victory), the matter of the CHMSL can was kicked down the road until 1986. The executives in Detroit were (and remain) "slippery slide' or "thin end of the wedge" theorists in that they thought if they agreed to some innocuous suggestion from government then that would encourage edicts both more onerous and expensive to implement. History proved them in that correct but the intriguing thing was that more than a decade earlier, the industry had gone beyond the the CHMSL and of its own volition offered DHMSLs (dual high mount stop lamps), one division of General Motors (GM) even on one model making the fittings standard equipment.

1970 Ford Thunderbird brochure (left) and 1972 Oldsmobile Toronado (right).

In 1969 Ford added “High-Level Taillamps, eye level warning to following drivers” to the option list for the 1970 Thunderbird. What that described was two brake lights fitted on either side of the rear-window and being a update of a model introduced for 1967, the devices were “bolt-ons” rather than being integrated into the structure. Because the Thunderbird was no longer available as a convertible, the option was available across the range which, uniquely in the fifth generation (1967-1971), included a four-door sedan. As with the “Lifeguard Design” of 1956, demand was low, customers more prepared to pay for bigger engines and “dress up” options than safety features. GM’s Oldsmobile Division solved the problem of low demand by making the DHMSLs standard equipment on the second generation Toronado (1971-1978), a big PLC (personal luxury coupe). Being a new body, the opportunity was taken to integrate the pair into the structure and neatly they sat below the rear window.

1987 Mercedes-Benz 560 SL (left), 1989 Mercedes-Benz 560 SL (centre) and 2001 Mercedes-Benz SL 600 (right).

When in 1971 the Mercedes-Benz 350 SL (R107, 1971-1989) was introduced, it occurred to no one it would still be in production in 1989, the unplanned longevity the product of (1) an uncertainty about whether the US government would outlaw convertibles and (2) the state of Western economies being often "difficult". The by then 15 year old roadster thus had to have a CHMSL added when the legislation came into effect and it’s tempting to suspect the project was handed to the same team responsible for making the company’s headlights and bumper bars comply with US law, both ventures usually with ghastly results. What they did was “bolt on” to the trunk (boot) lid a lamp which seemed to suggest the design brief had been: “make it stick out like a sore thumb”. If so, they succeeded and while the revised model (1988-1989) used a smaller unit, it was little more than a slightly less large digit; frankly, Ford did a better job with the 1970 T-bird although, in fairness, the Germans didn’t have a fixed rear window with which to work. When the R129 roadster (1989-2001) was developed, the opportunity was taken (al la the 1971 Oldsmobile Toronado) to integrate a CHMSL into the metal.

1989 Porsche 911 (930) Turbo Cabriolet (left) and 2004 Porsche 911 (996) Turbo Cabriolet.

In 1986, the Porsche 911 had been around longer even than the Mercedes-Benz R107. First sold in 1964 and updated for 1974 with (US mandated) big bumpers (which the factory handled with more aplomb than their Stuttgart neighbors), in 1986 it became another example of a “bolt on” solution for the CHMSL rule but unlike the one used on the R107, on the 911 there’s a charm to the lamp sitting atop a stalk, like that of some crustaceans, molluscs, insects and stalk-eyed imaginings from SF (science fiction). All the “bolt-ons” existed because while there is nothing difficult about the engineering of a CHMSL, many would be surprised to learn just how expensive it would have been for a manufacturer to integrate such a thing into an existing structure; a prototype or mock-up would be quick and cheap but translating that into series production would have involved a number of steps and the costs would have been considerable. That’s why there were so many “bolt-on” CHMSLs in the late 1980s. Interestingly, when the next 911 (964 1989-1994) was released, on the coupe’s the CHMSL was re-positioned at the top of the rear window while the cabriolets retained the stalk. The factory persevered with this approach for a while and it was only later the unit became integrated into the rear bodywork (with many variations). Some still prefer the look of the stalk because it's fine for something to "stick out like a sore thumb" if it's a good-looking digit.

For manufacturers and drivers alike, from the mid-1980s onward, CHMSLs became omnipresent yet despite their conspicuous visibility, were soon so unexceptional as to be in a sense unnoticed; they became just part of the orthodoxy of design language. Researchers however remained interested in the brake light and as early as the 1970s some were advocating the introduction of front brake lights (FBL), obviously a concept difficult to test in the wild because such things were almost universally unlawful. In test labs though their potential effectiveness could be studied by using simulators which compared a driver’s reaction time to the sight of a braking vehicle with and without FBLs and, unsurprisingly, where a warning light was present, reactions were faster and that can be of consequence in situations of potential impact at speed, a vehicle in a second travelling a considerable distance. The sort of statistical modelling applied to try to quantify the potential benefits FBLs might deliver can be criticized but there has been more than one research project and while the details have differed, all suggested there would be a reduction in vehicle crashes and logically, that should translate into less damage and fewer deaths & injuries. Paradoxically, were that to be realized, one direct effect would be a reduction in GDP (gross domestic product) because the economic activity generated (in industries such as medicine, car repair, funeral homes etc) wouldn’t happen although some of that would be off-set by the ongoing workforce participation by those not killed or hospitalized.

What FBLs would do is made it easier for drivers to detect another vehicle’s braking from front and side angles, making them more likely to react if a potential situation drama is thus anticipated. Obviously red lights at the front would be a bad idea (although some service vehicles are so equipped) and clear or amber lens could be ambiguous so the usual suggestion is green, previously used only by a small number of medical personnel. There were concerns about the use of green because it was speculated there might (especially in conditions of low visibility) be potential for them to be confused with the green (Go) of traffic signals used at intersections but to assess the veracity of that may require testing in real-world conditions.

1968 Citroën DS20 Break (left) and 1958 DeSoto Firesweep Explorer Station Wagon (right).

In 1958, a station wagon version of the DS & ID was released; because of historic regional variations in terminology, in different places it was marketed as the Break (France), Safari or Estate (UK), Station Wagon (North America) and Safari or Station Wagon (Australia) but between markets there were only detail differences. Because of the top-hinged tailgate, to mount the clignotants in the high positions used on the saloons would have been difficult so they were integrated into a vertical stack of three in a conventional location. In style the lens and the modest “fins” in which they sat recalled the arrangement DeSoto in the US had made their signature since late 1955 although it’s unlikely the US design had much influence on what was for Citroën a pragmatic solution for a vehicle then regarded as having most appeal as a Commerciale. The French certainly weren’t drawn to fins as macropterous as some Detroit had encouraged theirs to grow to by 1958.

Finettes: Bossaert's tail lights from the parts bin of Fiat (left) and BMC (right).

Convertibles of course lack a roof so the clignotants couldn’t continue in their eye-catching place with topless coachwork and their placement on the DS & ID varied in accordance with how the rear coachwork was handled. Bossaert took a conventional approach and emulated a look familiar on many European roadsters & cabriolets. For the GT 19 the taillights (known as carrellos) came from the Fiat Pininfarina Coupé & Cabriolet (1959-1966), a vertical style which in the era appeared on a number of cars including Ferraris, Peugeots and Rovers. For his other take on a convertible DS, Bossaert reached over the English Channel and from the BMC (British Motor Corporation) parts bin selected the units used by the Wolseley Hornet & Riley Elf (luxury versions of the Mini (1959-2000), built between 1969-1969 which, as well as the expected leather & burl walnut veneer trim, had an extended tail with distinctly brachypterous “finettes” (only Chevrolet seems to have used "finlets", applied to the foursome on the earliest (1953-1955) of the first generation (C1 1953-1962) Corvettes. The success of the Hornet & Elf in class-conscious England encouraged BMC in 1964 to go even more up-market and have their in-house coach-builder Vanden Plas produce a version of the Austin 1100 (ADO16, 1963-1974) and all the ADO16s until 1967 shared their taillights with the Hornet and Elf. Although visually similar to those used between 1962-1970 on MG’s MGB (1962-1980) & MGC (1967-1969); they are different, the Hornet/Elf/ADO16 units being the Lucas L549 while the MGs used the L550. Between 1961-1966, the MG Midget (1961-1980) used the L549 and between 1966-1970 the L550.

1970 Chapron Citroën DS20 Décapotable Usine (left), 1962 Chapron Citroën DS19 Concorde (with clignotants rouge, right) and 1965 Chapron Citroën DS21 Le Caddy (with clignotants ambre, right).

Chapron’s approach to clignotant placement varied with rear coachwork. On the volume models officially supported by the factory, two small lens were fitted within chrome housings, mounted on opposite sides at the base of the soft-top. For his more exclusive Le Caddy & Concorde with squared-off rear quarters (al la the “modernizing” look Mercedes-Benz applied to the 300 Adenauer W186, 1951-1957) to create the 300d (1957-1962)) Chapron re-purposed one of the existing taillights, using a still-lawful red lens on many although later models switched to amber.

1973 Citroën DS23 Pallas "landaulet" (in the style of that once used by the French president, left), 2010 Maybach 62 S Landaulet (to right), John Paul II (1920–2005; pope 1978-2005) in Papal 1965 Mercedes-Benz 300 SEL Landaulet (bottom left) and Paul VI (1897-1978; pope 1963-1978) with his 1966 Mercedes-Benz 600 Landaulet (bottom right).

From the moment it first was shown in 1955 the DS has intrigued and it’s the various convertibles which attract most attention. To this day, the things remain a symbol which quintessentially is French and at least two have been converted into “full-roof” landaulets for tourists to be escorted around Paris. The landaulet (a car with a removable roof which retains the side window frames) was a fixture on coach-building lists during the 1920s & 1930s but became rare in the post-war years; of late the only ones produced in any volume were the 59 Mercedes-Benz 600s (1963-1981) which came in “short” and “long” (though not full) roof versions although there was a revival, 22 Maybach 62 S Landaulets built between 2011-2022, one of which was even RHD. Considering the price and specialized nature of the variant, that there were 22 made makes the Landaulet more a success than the unfortunate "standard" Maybachs which managed only some 3300 between 2002-2013. The Papal Mercedes-Benz 300 SEL (W109) Landaulet was a gift from the factory but it was for years little used because the next year a very special 600 (W100) Pullman Landaulet was provided and this much more spacious limousine was preferred. The papal 600 was unique in that it was one of the “high roof” state versions and fitted with longer rear doors, a “throne” in the rear compartment which, mounted on an elevated floor, could be raised or lowered as Hid Holiness percolated through crowed streets. It was the latest in a long line of limousines and landaulets the factory provided for the Holy See and remains one of the best known; returned to the factory in 1985, it’s now on permanent display at the Mercedes-Benz museum in Stuttgart. Use of the 600 became infrequent after the attempted assassination of John Paul II (1981). As a stopgap, the 300 SEL quickly was armor-plated and used occasionally until the arrival of “Popemobiles” in which the pontiff sat in an elevated compartment with bullet-proof glass sides. Despite that, Mercedes-Benz have since delivered two S-Class (a V126 & V140) landaulets to the Vatican. Francis (b 1936; pope since 2013) has no taste for limousines or much else which is extravagant and prefers small, basic cars although to ensure security the bullet-proof Popemobiles remain essential and in 2024 Mercedes-Benz presented the Holy See with a fully-electric model, based on the new W465 G-Class. The Vatican is planning to have transitioned to a zero-emission vehicle fleet by 2030.

1974 Citroën DS23 Pallas: the one-off Australian “semi-phaeton”.

In Australia, someone created something really unique: a DS “semi-phaeton”. While the definition became looser until eventually it became merely a model name which meant nothing beyond some implication of exclusivity & high price, the term “phaeton” (borrowed from the age of the horse-drawn buggy) referred to a vehicle with no top or side windows. By the late 1930s, when last they were on the books as regular production models, the “phaetons” had gained folding tops and often removable side windows but they’d also lost market appeal and except for the odd few built for ceremonial purposes (the most memorable the three Chrysler Imperial Parade Phaetons built in 1952 and still occasionally used), there was no post-war revival. The Australian creation was based on a 1974 DS23 Pallas and had no soft-top or rear-side windows but the front-side units remained operative. The rear doors were changed to hinge from the rear (the so-called “suicide doors”; the external handles removed from all four), an indication the engineering was more intricate than many of the “four-door convertibles” made over the years by decapitating a sedan; the sales blurb did note the platform was “strengthened”, something essential when a structural component like a roof is removed.

The Citroën SM, a few of which were decapitated

1972 Citroën SM (left) & 1971 Citroën SM Mylord by Carrosserie Chapron (right). The wheels are the Michelin RR (roues en résine or résine renforcée (reinforced resin)) composites, cast using a patented technology invented by NASA for the original moon buggy. The Michelin wheel was one-piece and barely a third the weight of the equivalent steel wheel but the idea never caught on, doubts existing about their long-term durability and susceptibility to extreme heat (the SM had inboard brakes).

Upon release in 1971, immediately the Citroën SM was recognized as among the planet's most intricate and intriguing cars. A descendant of the DS which in 1955 had been even more of a sensation, it took Citroën not only up-market but into a niche the SM had created, nothing quite like it previously existing, the combination of a large (in European terms), front-wheel-drive (FWD) luxury coupé with hydro-pneumatic suspension, self-centreing (Vari-Power) steering, high-pressure braking and a four-cam V6 engine, a mix unique in the world. The engine had been developed by Maserati, one of Citroën’s recent acquisitions and the name acknowledged the Italian debt, SM standing for Systemé Maserati. Although, given the size and weight of the SM, the V6 was of modest displacement to attract lower taxes (initially 2.7 litres (163 cubic inch)) and power was limited (181 HP (133 kW)) compared to the competition, such was the slipperiness of the body's aerodynamics that in terms of top speed, it was at least a match for most.

However, lacking the high-performance pedigree enjoy by some of that competition, a rallying campaign had been planned as a promotional tool. Although obviously unsuited to circuit racing, the big, heavy SM didn’t immediately commend itself as a rally car; early tests indicated some potential but there was a need radically to reduce weight. One obvious candidate was the steel wheels but attempts to use lightweight aluminum units proved abortive, cracking encountered when tested under rally conditions. Michelin immediately offered to develop glass-fibre reinforced resin wheels, the company familiar with the material which had proved durable when tested under extreme loads. Called the Michelin RR (roues resin (resin wheel)), the new wheels were created as a one-piece mold, made entirely of resin except for some embedded steel reinforcements at the stud holes to distribute the stresses. At around 9.4 lb (4¼ kg) apiece, they were less than half the weight of a steel wheel and in testing proved as strong and reliable as Michelin had promised. Thus satisfied, Citroën went rallying.

The improbable rally car proved a success, winning first time out in the 1971 Morocco Rally and further success followed. Strangely, the 1970s proved an era of heavy cruisers doing well in the sport, Mercedes-Benz winning long-distance events with their 450 SLC 5.0 which was both the first V8 and the first car with an automatic transmission to win a European rally. Stranger still, Ford in Australia re-purposed one of the Falcon GTHO Phase IV race cars which had become redundant when the programme was cancelled in 1972 and the thing proved surprisingly competitive during the brief periods it was mobile although the lack of suitable tyres meant repeatedly the sidewalls would fail; the car was written off after a serious crash. The SM, GTHO & SLC proved a quixotic tilt and the sport went a different direction. On the SM however, the resin wheels had proved their durability, not one failing during the whole campaign and encouraged by customer requests, Citroën in 1972 offered the wheels as a factory option although only in Europe; apparently the thought of asking the US federal safety regulators to approve plastic wheels (as they’d already been dubbed by the motoring press) seemed to the French so absurd they never bothered to submit an application.

Ambitious as it was, circumstances combined in a curious way that might have made the SM more remarkable still. By 1973, sales of the SM, after an encouraging start had for two years been in decline, a reputation for unreliability already tarnishing its reputation but the first oil shock dealt what appeared to be a fatal blow; from selling almost 5000 in 1971, by 1974 production numbered not even 300. The market for fast, thirsty cars had shrunk and most of the trans-Atlantic hybrids (combining elegant European coachwork with large, powerful and cheap US V8s), which had for more than a decade done good business as alternative to the highly strung British and Italian thoroughbreds, had been driven extinct. Counter-intuitively, Citroën’s solution was to develop an even thirstier V8 SM and that actually made sense because, in an attempt to amortize costs, the SM’s platform had been used as the basis for the new Maserati Quattroporte but, bigger and heavier still, performance was sub-standard and the theory was a V8 version would transform both and appeal to the US market, then the hope of many struggling European manufacturers.

Citroën didn’t have a V8; Maserati did but it was big and heavy, a relic with origins in racing and while its (never wholly tamed) raucous qualities suited the character of the sports cars and saloons Maserati offered in the 1960s, it couldn’t be used in something like the SM. However, the SM’s V6 was a 90o unit and thus inherently better suited to an eight-cylinder configuration. In 1974 therefore, a four litre (244 cubic inch) V8 based on the V6 (by then 3.0 litres (181 cubic inch)) was quickly built and installed in an SM which was subjected to the usual battery of tests over a reported 20,000 km (12,000 miles) during which it was said to have performed faultlessly. Bankruptcy (to which the SM, along with some of the company's other ventures, notably the GZ Wankel programme, contributed) however was the death knell for both the SM and the V8, the prototype car scrapped while the unique engine was removed and stored, later used to create a replica of the 1974 test mule.

Evidence does however suggest a V8 SM would likely have been a failure, just compounding the existing error on an even grander scale. It’s true that Oldsmobile and Cadillac had offered big FWD coupés with great success since the mid 1960s (the Cadillac at one point fitted with a 500 cubic inch (8.2 litre) V8 rated at what sounds an alarming 400 HP (300 kW)) but they were very different machines to the SM and appealed to a different market. Probably the first car to explore what demand might have existed for a V8 SM was the hardly successful 1986 Lancia Thema 8·32 which used the Ferrari 308's 2.9 litre (179 cubic inch) V8 in a FWD platform. Although well-executed within the limitations the configuration imposed, it was about a daft an idea as it sounds although it did hint at what a success a V8 Fiat 130 saloon (1969-1976) & coupé (1971-1977) might have been if sold with a Lancia badge. Even had the V8 SM been all-wheel-drive (AWD) it would probably still have been a failure but it would now be remembered as a revolution ahead of its time. As it is, the whole SM story is just another cul-de-sac, albeit one which has become a (mostly) fondly-regarded cult.

State Citroëns by Carrosserie Chapron: 1968 Citroën DS state limousine (left) and 1972 Citroën SM Présidentielle (right).

In the summer of 1971, after years of slowing sales, Citroën announced the end of the décapotable usine and Chapron’s business model suffered, the market for specialized coach-building, in decline since the 1940s, now all but evaporated. Chapron developed a convertible version of Citroën’s new SM called the Mylord but, very expensive, it was little more successful than the car on which it was based; although engineered to Chapron’s high standard, fewer than ten were built. Government contracts did for a while seem to offer hope. Charles De Gaulle (1890–1970; President of France 1958-1969) had been aghast at the notion the state car of France might be bought from Germany or the US (it’s not known which idea he thought most appalling and apparently nobody bothered to suggest buying British) so, at his instigation, Chapron (apparently without great enthusiasm) built a long wheelbase DS Presidential model.

Size matters: Citroën DS Le Presidentielle (left) and LBJ era stretched Lincoln Continental by Lehmann-Peterson of Chicago (right).

Begun in 1965, the project took three years, legend having it that de Gaulle himself stipulated little more than it be longer than the stretched Lincoln Continentals then used by the White House (John Kennedy (JFK, 1917–1963; US president 1961-1963) was assassinated in Lincoln Continental X-100 modified by Hess and Eisenhardt) and this was achieved, despite the requirement the turning circle had to be tight enough to enter the Elysée Palace’s courtyard from the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré and then pull up at the steps in a single maneuver. Although size mattered on the outside, De Gaulle’s sense of “grandeur de la France” didn’t extend to what lay under the hood, Le Presidentielle DS retaining the 2.1 litre (133 cubic inch) 4 cylinder engine but he’d probably have scorned the 7.5 litre (462 cubic inch) V8 by then in Lincolns as typical American vulgarity. As it was, although delivered to the Élysée in time for the troubles of 1968, Chapron’s DS was barely used by De Gaulle because he disliked the partition separating him from the chauffeur and he preferred either the earlier limousines built in the 1950s by Franay and Chapron (both based on the earlier Citroën Traction Avant 15/6) or a DS landaulet (with full-length folding roof) in which he could stand up and look down on the (hopefully) cheering crowds lining the road.

However, the slinky lines must have been admired because in 1972 Chapron was commissioned to supply two really big four-door convertible Le Presidentielle SMs as the state limousines for Le Général’s successor, Georges Pompidou (1911–1974; President of France 1969-1974). First used for 1972 state visit of Elizabeth II (1926-2022; Queen of the UK and other places, 1952-2022), they remained in regular service until the inauguration of Jacques Chirac (1932–2019; President of France 1995-2007) in 1995, seen again on the Champs Elysees in 2004 during Her Majesty’s three-day state visit marking the centenary of the Entente Cordiale.

1972 Citroën SM Opera by Carrosserie Chapron (left) & 1973 Maserati Quattroporte II (right). This is the Quattroporte which was slated to receive the V8 tested in the SM.

Despite that, state contracts for the odd limousine, while individually lucrative, were not a model to sustain a coach building business and a year after the Mylord was first displayed, Chapron inverted his traditional practice and developed from a coupé, a four-door SM called the Opera. On a longer wheelbase, stylistically it was well executed but was heavy and both performance and fuel consumption suffered, the additional bulk also meaning some agility was lost. Citroën was never much devoted to the project because they had in the works what was essentially their own take on a four-door SM, sold as the Maserati Quattroporte II (the Italian house having earlier been absorbed) but as things transpired in those difficult years, neither proved a success, only eight Operas and a scarcely more impressive thirteen Quattroporte IIs ever built. The French machine deserved more, the Italian knock-off, probably not. In 1974, Citroën entered bankruptcy, dragged down in part by the debacle which the ambitious SM had proved to be although there had been other debacles worse still.

That other quintessential symbol of France, Brigitte Bardot (1934-2025) in La Déesse with a lit Gitanes.

The combination of a car, a woman with JBF and a cigarette continued to draw photographers even after smoking ceased to be glamorous and became a social crime. First sold in 1910, Gitanes production in France survived two world wars, the Great Depression, Nazi occupation but the regime of Jacques Chirac (1932–2019; President of France 1995-2007) proved too much and, following the assault on tobacco by Brussels and Paris, in 2005 the factory in Lille was shuttered. Although Gitanes (and the sister cigarette Gauloise) remain available in France, they are now shipped from Spain and while in most of the Western world fewer now smoke, Gitanes Blondes retain a cult following. Three years after the last SM left the factory, Henri Chapron died in Paris, his much down-sized company lingering on for some years under the direction of his industrious widow, the bulk of its work now customizing Citroën CXs. Operations ceased in 1985 but the legacy is much admired and the décapotables remain a favorite of collectors and film-makers searching for something with which to evoke the verisimilitude of 1960s France.

Grave of Monsieur et Madame Arbelot, Cimetière du Père Lachaise, Paris.

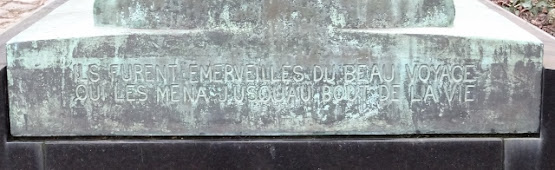

In most circumstances, the sight of a husband staring at the decapitated head of his wife which he’s holding aloft before his eyes would be at least confronting and usually an indication he may have committed at least one offence but there is, carved in stone in a Parisian cemetery, one such decapitation which is romantic. In the Cimetière du Père Lachaise (Rueil-Malmaison, Departement des Hauts-de-Seine) lie the graves of Fernand (Louis) Arbelot (1880-1942) and his wife Henriette Marie Louise Gicquel (1885-1967), the couple married in the city in August 1919. It was during her funeral in 1967 they finally were reunited and the bronze statue of a recumbent Monsieur Arbelot holding in his hands the face of his beloved is a monument to his one wish when dying: to forever gaze upon the face of his wife. The epitaph on the grave reads: Ils furent émerveillés du beau voyage qui les mena jusqu’au bout de la vie (They were amazed by the beautiful journey that led them to the end of life).

Epitaph on grave of Monsieur et Madame Arbelot, Cimetière du Père Lachaise, Paris.

Established in 1803 by Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821; leader of the French Republic 1799-1804 & Emperor of the French from 1804-1814 & 1815) and named after the Jesuit priest, Père François de la Chaise (1624–1709) who was confessor to Louis XIV (1638–1715; le Roi Soleil (the Sun King), King of France 1643-1715), at 40 hectares (100 acres), Père Lachaise remains Paris's largest cemetery and contains over a million internments. Apart from the obvious matter of the many dead, it’s of interest to historians of town planning because as a piece of landscape architecture, it represented an change of approach from the old, over-crowded medieval churchyards in which corpses had for centuries be piled one atop the other. Although not strictly true, the place has come to be regarded as the first “garden” or “landscape” cemetery and even the French admit there was influence from the eighteenth century country houses of the English aristocracy & landed gentry, the grounds of which were characterized by irregular, winding paths and picturesque gardens with a seemingly (and sometime literally) random, naturalistic approach to plantings. It was also one of Napoleon’s more far-sighted decisions because although initially unpopular because of its distance from the city, Paris quickly expanded to “meet” it and the vast space made possible to purchase of individual plots, once a privilege available only to the rich.

Attracting each year more than four million tourists, Cimetière du Père Lachaise is one of the world’s more-visited graveyards and it features frequently on Instagram & TikTok, the favoured dead celebrities including the Irish author Oscar Wilde (1854-1900) although his memorial is now less photogenic because the carving of a sleeping winged sphinx had to be placed behind plexiglass to prevent the “theft of certain private parts” and protect it from the lipstick-covered kisses of devotees (left by women as well as men it’s said). Other popular fan-graves include those of Polish composer Frédéric Chopin (1810–1849), US singer Jim Morrison (1943-1971), Italian artist of the Paris School Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920), French singer Édith Piaf (1915–1963), French novelist Marcel Proust (1871–1922), US writer Gertrude Stein (1874–1946) and the French pioneer of sociology Auguste Comte (1798–1857).

Judith and the decapitation of Holofernes

In the Bible, the deuterocanonical books (literally “belonging

to the second canon”) are those books and passages traditionally

regarded as the canonical texts of the Old Testament, some of which long

pre-date Christianity, some composed during the “century of overlap” before

the separation between the Christian church and Judaism became institutionalized. As the Hebrew canon evolved, the seven

deuterocanonical books were excluded and on this basis were not included

in the Protestant Old Testament, those denominations regarding them as apocrypha

and they’re been characterized as such since.

Canonical or not, the relationship of the texts to the New Testament has

long interested biblical scholars, none denying that links exist but there’s

wide difference in interpretation, some finding (admittedly while giving

the definition of "allusion" wide latitude) a continuity of thread, others only

fragmentary references and even then, some paraphrasing is dismissed as having

merely a literary rather than historical or theological purpose.

The Book of Judith exists

thus in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Old Testaments but is assigned

(relegated some of the hard-liners might say) by Protestants to the apocrypha. It is the tale of Judith (יְהוּדִית

in the Hebrew and the feminine of Judah), a legendarily beautiful Jewish widow who uses her charms to

lure the Assyrian General Holofernes to his gruesome death (decapitated by her

own hand) so her people may be saved. As

a text, the Book of Judith is interesting in that it’s a genuine literary

innovation, a lengthy and structured thematic narrative evolving from the one

idea, something different from the old episodic tradition of loosely linked

stories. That certainly reflects the

influence of Hellenistic literary techniques and the Book of Judith may be

thought a precursor of the historical novel: A framework of certain agreed

facts upon a known geography on which an emblematic protagonist (Judith the feminine

form of the national hero Judah) performs.

The atmosphere of crisis and undercurrent of belligerence lends the work

a modern feel while theologically, it’s used to teach the importance of

fidelity to the Lord and His commandments, a trust in God and how one must

always be combative in defending His word.

It’s not a work of history, something made clear in the first paragraph;

this is a parable.

Judit decapitando a Holofernes (Judith Beheading Holofernes) (circa 1600) by Caravaggio (Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1571–1610).

The facts of the climactic moment in the decapitation of General

Holofernes are not in dispute, Judith at the appropriate moment drawing the

general’s own sword, beheading him as he lay recumbent, passed out from too

much drink. Deed done, the assassin dropped the separated head in a leather basket and stole away. The dramatic tale for centuries has attracted

painters and sculptors, the most famous works created during the high Renaissance

and Baroque periods and artists have tended to depict either Judith acting

alone or in the company of her aged maid, a difference incidental to the murder

but of some significance in the interpretation of preceding events.

All agree the picturesque widow was able to gain access to the tent of Holofernes because of the

general’s carnal desires but in the early centuries of Christianity, there’s

little hint that Judith resorted to the role of seductress, only that she lured

him to temptation, plied him with drink and struck. The sexualization of the moment came later

and little less controversial was the unavoidable juxtaposition of the masculine

aggression of the blade-wielding killer with her feminine charms. Given the premise of the tale and its moral

imperative, the combination can hardly be avoided but it was for centuries

disturbing to (male) theologians and priests, rarely at ease with bolshie women. It was during the high Renaissance that

artists began to vest Judith with an assertive sexuality (“from Mary to Eve” in

the words of one critic), her features becoming blatantly beautiful, the

clothing more revealing. The Judith of the Renaissance and the Baroque appears one

more likely to surrender her chastity to the cause where once she would have

relied on guile and wine.

It was in the Baroque period that the representations more explicitly made possible the mixing of sex and violence in the minds of viewers, a combination that across media platforms remains today as popular as ever. For centuries “Judith beheading Holofernes” was one of the set pieces of Western Art and there were those who explored the idea with references to David & Goliath (another example of the apparently weak decapitating the strong) or alluding to Salome, showing Judith or her maid carrying off the head in a basket. The inventiveness proved not merely artistic because, in the wake of the ruptures caused by the emergent Protestant heresies, in the counter-attack by the Counter-Reformation, the parable was re-imagined in commissions issued by the Holy See, Judith’s blade defeating not only Assyrian oppression but all unbelievers, heretical Protestants just the most recently vanquished. Twentieth century artists too have used Judith as a platform, predictably perhaps sometimes to show her as the nemesis of toxic masculinity and some have obviously enjoyed the idea of an almost depraved sexuality but there have been some quite accomplished versions.