Tantrum (pronounced tan-truhm)

(1) A violent demonstration of rage or frustration; a

sudden burst of ill temper, most associated with children but widely applied to

the childish outbursts of adults.

(2) To have a tantrum.

1714: One of English’s etymological mysteries, other than

being derived from the earlier tanterum,

the origin is so obscure there’s no evidence on which to base speculation and

while the first known reference in writing is from 1714, it’s likely it had

been in (presumably colloquial) oral use for some time. There are conventions of use such as “temper

tantrum” & the common intransitive “throw a tantrum”; synonymous words and

phrases include angry outburst, flare-up, fit of rage, conniptions, dander, huff,

hysterics, storm, wax, hissy fit & dummy spit. The noun plural is tantrums and the rarely

used present participle is tantruming (or tantrumming), the past participle

tantrumed (or tantrummed).

Social media, SMS or email posts in ALL CAPS or with an extravagant

use of question marks (?????) or exclamation marks (!!!!!) convey shouting and

are the textual version of a tantrum although this understanding was learned behaviour;

many early systems (Telix etc) available only with upper case characters so there

was a greater dependency on (?????) & (!!!!!) to denote anger, the asterisk

(*****) & hash (#####) symbols inserted to permit vulgarities (f**k, sh##

et al) to be understood without being spelled out. That was a work-around of some significance

because the telecommunication legislation in many nations actually prohibited swearing

(even on telephone voice calls) over what was then called a “carriage service”,

typical wording in the acts being something like:

It shall be unlawful for any

person in the operation of any telephone installed within the city, to make use

of any vulgar vituperation or profane language into and over such telephone. (Profanity over

telephone: (Code of ordinances, Colombus Georgia, USA, (§ 663 (1914)), Section 14-49)

Such laws probably still exist in many places but

instances of enforcement are doubtless rare.

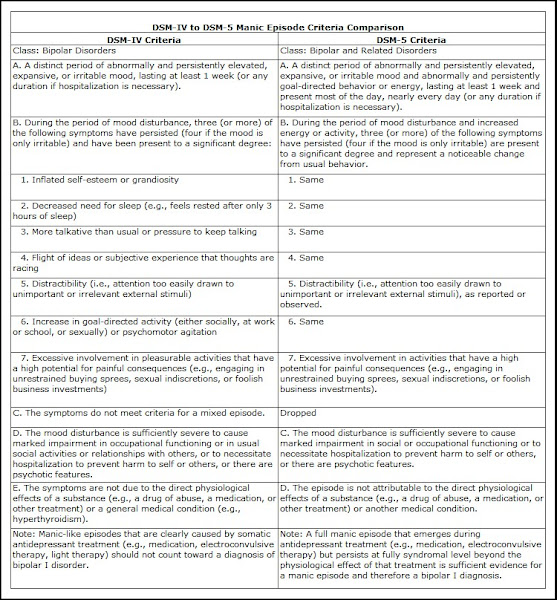

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD)

Remarkably, as a definable condition, the temper tantrum

wasn’t medicalized (as a distinct diagnosis) until 2013 when the fifth edition

of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) was published. Named Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder

(DMDD), it was classified as a mood disorder noted as affecting children aged 6-18,

an unusual concession by the industry that tantrums in very young children are

a normal and healthy (if annoying) aspect of human development.

DMDD was thus a new diagnosis but it really was a shift

in classification, reflecting the early twenty-first century view that both the

autism spectrum and bipolar disorder (BD, the old manic-depression) were being

over-diagnosed. Also a condition that

can cause extreme changes in mood, it was noted that misdiagnosing BD can

result in unnecessary medications being prescribed, the long-term use of which were

associated with side effects including weight gain, lipid & glucose

abnormalities and reduced brain volume (and

a diminished number of neurons in the brain).

Thus it being undesirable that BD be over-diagnosed in the young, DMDD

exists as an alternative and, although many of the mood-related symptoms overlap

with BD, there are as yet no FDA (the US Food and Drug Administration) approved

medications for children or adolescents with DMDD and in the recent history of

the DSM, that’s unusual. There have been

instances of updates to the DSM removing diagnoses while the specified drug

remains on the FDA schedule but it’s rare for one to appear without an approved

medication, the symbiosis between the industries usually well-synchronized. Advice to clinicians continue to include the

note that stimulants, antidepressants, and atypical antipsychotics can be used to

help relieve a child’s DMDD symptoms but that side effects would need to be monitored,

individual and family therapy to address emotion-regulation skills a desirable

alternative to be pursued where possible.

The behavioral distinction between DMDD and BD is that subjects don’t

experience the episodic mania of a child with BD and they’re at no greater risk

of later developing BD although there is a higher anxiety as an adult. Because of the potentially stigmatizing

effects (possibly for life) of a diagnosis of BD, that’s something which should

be applied only with a strict application of the criteria.

It’s further noted that DMDD is a diagnosis that should

apply to a specific type of mood (the tantrum) distinguished by being extreme

and/or frequent; it should thus (as parents have doubtless always regarded tantrums)

be thought a spectrum condition. The

markers include (1) severe, chronic irritability, (2) severe verbal or

behavioral tantrums, several times weekly for at least a year, (3) reactions

out of proportion to the situation, (4) difficulty functioning because of

outbursts and tantrums, (5) aggressive behavior & (6) a frequent

transgression of rules. Observationally,

DMDD may be indicated by (7) trouble in socializing and forming friendships,

(8) physically aggression towards peers and family and even (9) difficulties in

the cooperative aspects of playing team sports (although not merely a

preference for individual disciplines).

The diagnostic criteria for DMDD require a child to have experienced

tantrums (which are severe and/or of long duration) at least three times weekly

for at least a year’ especially if between episodes they’re also chronically

irritable. However, if the tantrums are

geographically or situationally specific (ie happen only at school or only at

church etc) then DMDD may not be the appropriate diagnosis and other disorders

(childhood bipolar disorder (CBD), autism, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD)

or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)) may need to be considered. A particular difficulty in the diagnostic

process is that not only is there a significant overlap of symptoms in these

disorders but instances of conditions themselves can co-exist. With children, it’s recommended that when

possible, DMDD treatment begins with therapy (psychotherapy and parent

training), medications prescribed only later in treatment or at least starting in

conjunction with therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) thought helpful.

Noted temper tantrums

3 Ketchup Bottles (2021) by Kristin Kossi (b 1984), Acrylic on Canvas, US$8000 at Singulart.

Details of President Trump’s (Donald Trump, b 1946, US

president 2017-2021) tantrum which included his ketchup laden lunch ending up oozing

down an Oval Office wall were recounted during the congressional hearings into

matters relating to the attempted insurrection on 6 January 2021. Although apparently not the first time plates

were smashed in the Trump White House during episodic presidential petulance,

such outbursts by heads of government are not rare. Indeed, given the stress and public scrutiny

to which such folk are subject, it’s surprising there aren’t more although it’s

usually only years later, as memoirs emerge, that the tales are told.

Warren Harding (1865–1923; US president 1921-1923) was once

observed strangling a government official with his bare hands although that

might have been understandable, his administration notoriously riddled with

corruption. When Harding dropped dead

during his term, it was probably a good career move.

Adolf Hitler’s (1889-1945; head of state (1934-1945) and

government (1933-1945) in Nazi Germany) ranting meltdown in the Führerbunker on

21 April 1945 as the Red Army closed on Berlin became a tantrum of legend and

was the great set piece of the film Downfall (2004) about the last days of the

Third Reich, a scene which has since generated hundreds of memes.

Even before the Watergate scandal began to consume his

presidency, Richard Nixon (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974) was known for his

temper tantrums, often under the influence of alcohol. His aides would later recount his

expletive-laden tirades during which, apparently seriously, he would order

bombings, missile launches and assassinations (all of which were ignored). His predecessor’s, (Lyndon Baines Johnson

(LBJ), 1908-1973, US president 1963-1969) moods were said to be just as volatile

and during episodes he would sometimes wish for whole countries to be destroyed

although he stopped short actually of ordering it.

Admiring glance: George Stephanopoulos looking at crooked Hillary Clinton.

Reports of Bill Clinton’s (b 1946; US president 1993-2001) tantrums

tend to emphasize their frequency and intensity but note also how quickly they

subsided. In the memoir of George

Stephanopoulos ((b 1961; White House Communications Director 1993 &

presidential advisor 1993-1996)) focusing on his time as communications

director, it’s recounted that Clinton regularly lost his temper and would yell

at the staff, the in-house code for the outbursts being “purple fits”, so named

because of how red Clinton’s face became during the SMOs “Standard Morning

Outbursts”. Secret Service staff later interviewed

were kinder in their recollections of the president but seemed still traumatized

when describing his wife’s volcanic temper and Bill Clinton’s outbursts do need

to be viewed in the context of him being married to crooked Hillary Clinton (b

1947).

Anthony Eden (1897–1977; UK prime-minister 1955-1957) was

elegant, stylish and highly strung; one of his colleagues, in a reference to

his parentage, described Eden as “half

mad baronet, half beautiful woman” and his great misfortune was to become prime-minister,

the role for which he’d so long been groomed. Ill-suited to the role and in some ways unlucky, his tantrums became the stuff of Westminster

and Whitehall folklore, reflected in the diary entry of Winston Churchill’s

(1875-1965; UK prime-minister 1940-1965 & 1951-1955) physician (Lord Moran, 1885-1975) on 21 July 1956: “The

political world is full of Eden's moods at No 10 (Downing Street, the PM’s

London residence)”. The tales of his

ranting and raging appeared in much that was published after his fall from office

but in the years since, research suggests there was both exaggeration and some outright

invention, one contemporary acknowledging that while Eden certainly was highly

strung, “…he seldom became angry when

really important matters were involved, but instead did so over irritating

trivialities, usually in his own home, and very seldom did he lose his temper

in public”. Unfortunately, the best-known "tantrum" story of the 1956 Suez Crisis in which Eden is alleged to have thrown an full inkwell

at someone with whom he disagreed (a rubbish bin said to have been jammed on his head in

response), is almost certainly apocryphal.