Corporal (pronounced kawr-per-uhl or kaw-pruhl)

(1) Of the human body; bodily; physical

(2) In zoology, of the body proper, as distinguished from the head and limbs.

(3) As corporeal, belonging to the material world (mostly obsolete except for historic references although still used as a technical term in philosophy).

(4) In ecclesiastical accoutrements, a fine cloth, usually of linen, on which the consecrated elements are placed or with which they are covered during the Eucharist (also called the communion cloth).

(5) In Christian theology, as the seven Corporal Works of Mercy, the practical acts of compassion, as distinct from the seven Spiritual Works (the contemplative acts).

(6) In military use, a non-commissioned officer ranking above lance corporal (private first class (PFC) in US Army) and below a sergeant; in the Royal Navy, a petty officer who assists the master-at-arms; similar use in the armed services of many countries.

1350–1400: From the Middle English corporall, from the Anglo-French corporall, from the Latin corporālis (bodily, of the body) from corpus (body), the construct being corpor- (stem of corpuscorpus) + -ālis (the third-declension two-termination suffix (neuter -āle), used to form adjectives of relationship from nouns or numerals, from the primitive Indo-European -li-, which later dissimilated into an early version of -aris). The use describing alter cloths was derived from the Medieval Latin corporāle pallium eucharistic (altar cloth) and replaced corporas, itself inherited from Classical Latin under the influence of Old French. The pronunciation is kaw-pruhl in military use and kawr-per-uhl for all other purposes. The adoption by the military dates from 1570–1580 but the origin is uncertain. It may have come from the Old French (via Italian) into Middle French as a variant of caporal, from the Italian caporale, apparently a contraction of phrase capo corporale (corporal head) in the sense of the head of a body (of soldiers). Source was the Latin caput (head), perhaps influenced also by the Old French corps (body (of men)). Corporal is a noun & adjective, corporality, corporalcy & corporalship are nouns and corporally is an adverb; the noun plural is corporals.

The strategic corporal

The

idea of the “strategic corporal” was first explained in a paper published in

1999 by USMC (US Marine Corps) General Charles Krulak (b 1942). Based on both practical experience and his

analysis of the likely evolution of conflicts into localized, small-scale but

intense theatres of operation, he described what he called the “three block war”

in which the Marines could be involved in conventional fire-fights, peacekeeping

operations and humanitarian aid, all conduced in a geographical area no bigger

than three city blocks and undertaken either sequentially or, more

challengingly, simultaneously and in an environment in which hostile, friendly

& neutral forces are intermeshed. The

reference to the “three city blocks” was included for didactic purposes to

illustrate his point that the training of military personnel needed to be refined

better to encompass those required to make independent decisions, including the

non-commissioned officers (NCOs) & junior officers actually commanding small

numbers of troops on the ground. Just as

the term “three blocks” wasn’t a literal limitation but a way of illustrating a

change of mindset from the traditional focus on divisional & brigade level

deployment, the phrase “strategic corporal” was chosen because in the military

that is the lowest rank at which a soldier is in command of others and thus in

a position to make decisions which could have some strategic significance. Typically, a “strategic corporal” might be a lieutenant

who in modern warfare, must be trained to make major decisions without the

benefit of direction from the chain of command.

The

concept has been influential in many militaries and has been compared with the

idea of the “man on the ground” doctrine which emerged in the nineteenth

century when the early technologies of long-distance communication meant that

for the first time it was practical for military commanders in remote locations

to seek and receive instructions from perhaps thousands of miles away. It would however be decades before those

interactions habitually became real-time so the idea of the “strategic corporal”

would not then have been unfamiliar and there was an at least tacit

acknowledgement that the man on the ground would often be the one making critical

decisions rather than anyone in the high command or even the headquarters staff

in theatre. This could of course mean a

bad decision could theoretically trigger a war but as "the Fashoda Incident" (1898 and the retrospective re-naming of what was at the time in Paris and

London thought of as “the Fashoda Crisis”) illustrated, the man on the ground having

the necessary background and training to make a decision based on factors

beyond what was militarily possible could have far-reaching consequences.

So

the idea of the strategic corporal is that training in such matters needs to

extend to the layers of command where such decisions need to be made, not to

the point at which formerly they’re delegated or devolved. In a sense that of course is a mere

recognition of reality but the elevation of the concept into a doctrine has

been criticized as becoming “mythologized within the military culture [and] forever

associated with negative consequences”, the result of the ultimate responsibility

for decisions being seen through legal filters, leaders now too “…concerned

with the perceived risk..” and as a means to manage that “…senior leaders have

elevated decision authorities far away from anyone but themselves”.

Military

analysts have noted that military operations conducted in the Gaza Strip

provide the perfect example of a “three block war”, one that has the potential

to unfold as a series of “three block” theatres. In these urban environments in which a

civilian population co-exists still in high-density with paramilitary forces

and irregular combatants, decisions taken by a soldier in direct command of

fewer than a dozen troops in the invading army can have a strategic

significance well beyond the particular three blocks in which they’re operating.

Complicating this is the suspicion

expressed by some that a high civilian death-toll is actually an outcome desired

by the Hamas (Hamas the acronym of the Arabic

حركة المقاومة

الإسلامية (Ḥarakah

al-Muqāwamah al-ʾIslāmiyyah) (Islamic Resistance Movement); HMS glossed in

the Hamas Covenant (1998) by the Arabic word ḥamās

(حماس) (which translates variously as “strength”,

“zeal” or “bravery”)). The evidence to

support this is strong in that the nature of the attack staged by the Hamas on

Israeli civilians on 7 October 2023 was of such a nature that retaliation by

the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) would be bound to result in civilian causalities in

Gaza; there are not effective alternative military tactics available, the

choices being only to retaliate or not.

The

idea used by Hamas is not new. In 1942,

the Czechoslovak government-in-exile (which in 1940 had shifted from Paris to

London), had become especially disturbed by the success SS-Obergruppenführer (general)

Reinhard Heydrich (1904–1942; head of the Reich Security Main Office 1939-1942)

was enjoying as Deputy Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, a role in which he was

effectively the Nazi’s “governor of Czechoslovak”. Using the Nazi’s tradition method of governing

conquered territories by “carrot & stick” Heydrich had not spared the stick

early in his administration (1941-1942) but been remarkably successful with the

inducements he offered and had achieved an unexpectedly high degree of

cooperation with the local population.

With little signs of an effective resistance movement operating, the government

in exile took the decision, in cooperation with the British Special Operations

Executive (SOE), to send an assassination squad to Prague, knowing full well

the retribution against the population would be severe but the object was to

use that to stimulate local resistance.

More than a thousand Czechs were killed in revenge for Heydrich’s death.

So

in the awful business of war, civilian deaths can be thought of as useful

political devices, something which in Islamic theology is regarded as the noble

sacrifice of martyrdom. The Hamas,

having concluded (not unreasonably) that 75 years on, the leaders of many Arab

states had tired of the Palestinian “problem” and were moving on, regarding the

Jewish state as a permanent part of the region’s political geography with the

advantages of détente greater than those of conflict, needed to be back on the

agenda. The Hamas understand a resort to

diplomacy is unlikely much to influence the Arab rulers but the spilling of

Muslim blood at the hands of the IDF will bring protest to the streets in the

region and beyond. This

of course makes inevitable that when the strategic corporals proceed, however

cautiously, through the rubble of Gaza’s blocks, they’ll be encouraged by their

opponents to make decisions and these decisions can have consequences which ripple

far and perhaps for a generation. What one

strategic corporal decides to do really does matter. By comparison, most of the statements and resolutions, issued or passed by politicians, ex-politicians and other

worthies around the planet will be noted with equal interest by those in Tel Aviv, the Hamas to the south, the

Hezbollah to the north, the Ayatollahs to the east and the fish to the west.

Corporal and Spiritual Works of Mercy

The Bible reduces the New Testament’s conception of mercy to seven practical (corporal) and seven spiritual (contemplative) acts, each said to be a virtue influencing one's will to have compassion for, and, if possible, ameliorate another's misfortune. Italian Dominican friar & philosopher Saint Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) thought that although mercy is, as it were, the spontaneous product of charity, it must be thought a special virtue adequately distinguishable from its effects. Later theologians noted its motive is the misery which one discerns in another, particularly in so far as this condition is deemed to be, in some sense at least, involuntary but even if not, the necessity is to offer succor of either body or soul.

Corporal works of mercy

To feed the hungry

To give drink to the thirsty

To clothe the naked

To harbor the harborless

To visit the sick

To ransom the captive

To bury the dead

Spiritual works of mercy

To instruct the ignorant

To admonish sinners

To bear wrongs patiently

To forgive offences willingly

To comfort the afflicted

To pray for the living and the dead

To counsel the doubtful

The Gospel of Matthew (Matthew 25:34-41) makes clear those who offer mercy “…are righteous and their souls will be granted eternal life…” whereas those who do not “…shall be cursed, cast into everlasting fire and given over to the devil.”

34 Then shall the King say unto them on his right hand, Come, ye blessed of my Father, inherit the kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world:

35 For I was an hungred, and ye gave me meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me drink: I was a stranger, and ye took me in:

36 Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.

***

41 Then shall he say also unto them on the left hand, Depart from me, ye cursed, into everlasting fire, prepared for the devil and his angels:

42 For I was an hungred, and ye gave me no meat: I was thirsty, and ye gave me no drink:

43 I was a stranger, and ye took me not in: naked, and ye clothed me not: sick, and in prison, and ye visited me not.

46 And these shall go away into everlasting punishment: but the righteous into life eternal.

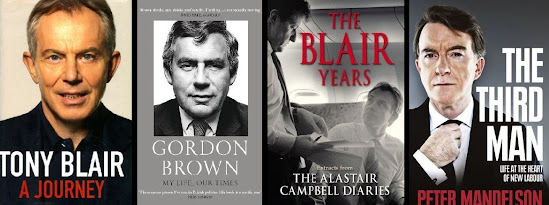

Tony Abbott (b 1957; Australian prime-minister 2013-2015) visited Cardinal George Pell (1941-2023) in prison (a corporal work of mercy). In this act, come Judgement Day, he will be found to have acted righteously.

Pope Francis (b 1936; pope since 2013) didn't visit Cardinal Pell in prison but did remember him in his prayers (a spiritual work of mercy). In this act, come Judgement Day, he will be found to have acted righteously. Within the Roman Curia (a place of Masonic-like plotting & intrigue and much low skulduggery), Cardinal Pell's nickname was “Pell Pot”, an allusion to Pol Pot (1925–1998, dictator of communist Cambodia 1976-1979) who announced the start of his regime was “Year Zero” and all existing culture and tradition must completely be destroyed and replaced.

Lindsay Lohan 6126 wool blend military coat in black.

Military uniforms have long influenced fashion and in the 1960s, the counter culture adopted them with some sense of irony. Camouflage patterns have always been popular but the dress uniforms are also used as a model, the insignia, sometimes in elaborated form added as embellishments. The insignia of a corporal is a two-bar chevron, depicted variously upwards or downwards, depending on the service.