Mini (pronounce min-ee)

(1) A skirt or dress with a hemline well above

the knee, popular since the 1960s.

(2) A small car, build by Austin, Morris,

associated companies and successor corporations between 1959-2000. Later reprised by BMW in a retro-interpretation.

(3) As minicomputer, a generalized (historic) descriptor

for a multi-node computer system smaller than a mainframe; the colloquial term mini

was rendered meaningless by technological change (Briefly, personal computers (PC) were known as

micros).

(4) A term for anything of a small, reduced, or

miniature size.

Early 1900s: A shorted form of miniature, ultimately from the Latin minium (red lead; vermilion), a development influenced by the similarity to minimum and minus. In English, miniature was borrowed from the late sixteenth century Italian miniatura (manuscript illumination), from miniare (rubricate; to illuminate), from the Latin miniō (to color red), from minium (red lead). Although uncertain, the source of minium is thought to be Iberian; the vivid shade of vermilion was used to mark particular words in manuscripts. Despite the almost universal consensus mini is a creation of twentieth-century, there is a suggested link in the 1890s connected with Yiddish and Hebrew.

As a prefix, mini- is a word-forming element meaning "miniature, minor", again abstracted from miniature, with the sense presumed to have been influenced by minimum. The vogue for mini- as a prefix in English word creation dates from the early 1960s, the prime influences thought to be (1) the small British car, (2) the dresses & skirts with high-hemlines and (3) developments in the hardware of electronic components which permitted smaller versions of products to be created as low-cost consumer products although there had been earlier use, a minicam (a miniature camera) advertised as early as 1937. The mini-skirt (skirt with a hem-line well above the knee) dates from 1965 and the first use of mini-series (television series of short duration and on a single theme) was labelled such in 1971 and since then, mini- has been prefixed to just about everything possible. To Bridget Jones (from Bridget Jones's Diary (1996) a novel by Helen Fielding (b 1958)), a mini-break was a very short holiday; in previous use in lawn tennis it referred to a tiebreak, a point won against the server when ahead.

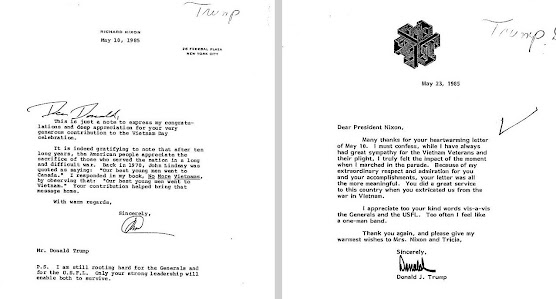

Jean Shrimpton and the mini-skirt

Jean Shrimpton, Flemington Racecourse, Melbourne, 1965.

The Victorian Racing Club (VRC) had in 1962 added Fashions on the Field to the Melbourne’s Spring Racing Carnival at Flemington and for three years, women showed up with the usual hats and accessories, including gloves and stockings, then de rigueur for ladies of the Melbourne establishment. Then on the VRC’s Derby Day in 1965, English model Jean Shrimpton (b 1942) wore a white mini, its hem a daring four inches (100 mm) above the knee. It caused stir.

The moment has since been described as the pivotal moment for the introduction of the mini to an international audience which is probably overstating things but for Melbourne it was certainly quite a moment. Anthropologists have documented evidence of the mini in a variety of cultures over the last 4000 odd years so, except perhaps in Melbourne, circa 1965, it was nothing new but that didn’t stop the fashion industry having a squabble about who “invented” the mini. French designer André Courrèges (1923-2016) explicitly claimed the honor, accusing his London rival to the claim, Mary Quant (b 1930) of merely “commercializing it”. Courrèges had shown minis at shows in both 1964 and 1965 and his sketches date from 1961. Quant’s designs are even earlier but given the anthropologists’ findings, it seems a sterile argument.

Minimalism: Lindsay Lohan and the possibilities of the mini.

The Mini

1962 Riley Elf.

The British Motor Corporation (BMC) first released their Mini in 1959, the Morris version called the Mini Minor (a link to the larger Minor, a model then in production) while the companion Austin was the Seven, a re-use of the name of a tiny car of the inter-war years. The Mini name however caught on and the Seven was re-named Mini early in 1962 although the up-market (and, with modifications to the body, slightly more than merely badge-engineered) versions by Riley and Wolseley were never called Mini, instead adopting names either from or hinting at their more independent past: the Elf and Hornet respectively. The Mini name was in 1969 separated from Austin and Morris, marketed as stand-alone marque until 1980 when the Austin name was again appended, an arrangement which lasted until 1988 when finally it reverted to Mini although some were badged as Rovers for export markets. The Mini remained in production until 2000, long before then antiquated but still out-lasting the Metro, its intended successor.

1969 Austin Maxi 1500.

The allure of the Mini name obviously impressed BMC. By 1969, BMC had, along with a few others, been absorbed into the Leyland conglomerate and the first release of the merged entity was in the same linguistic tradition: The Maxi. A harbinger of what was to come, the Maxi encapsulated all that would go wrong within Leyland during the 1970s; a good idea, full of advanced features, poorly developed, badly built, unattractive and with an inadequate service network. The design was so clever that to this day the space utilization has rarely been matched and had it been a Renault or a Citroën, the ungainly appearance and underpowered engine might have been forgiven because of the functionality but the poor quality control, lack of refinement and clunky aspects of some of the drivetrain meant success was only ever modest. Like much of what Leyland did, the Maxi should have been a great success but even car thieves avoided the thing; for much of its life it was reported as the UK's least stolen vehicle.

Curiously, given the fondness of BMC (and subsequently Leyland) for badge-engineering, there was never an MG version of the Mini (although a couple of interpretations were privately built), the competition potential explored by a joint-venture with the Formula One constructors, Cooper, the name still used for some versions of the current BMW Mini. Nor was there a luxury version finished by coachbuilders Vanden Plas which, with the addition of much timber veneer and leather to vehicles mundane, provided the parent corporations with highly profitable status-symbols with which to delight the middle-class. There was however a separate development by Leyland's South African operation (Leykor), their Vanden Plas Mini sold briefly between 1978-1979 although the photographic evidence suggests it didn’t match the finish or appointment level of the English-built cars which may account for the short life-span and it's unclear whether the head office approved or even knew of this South African novelty prior to its few months of life. In the home market, third-party suppliers of veneer and leather such as Radford found a market among those who appreciated the Mini's compact practicality but found its stark functionalism just too austere.

The Twini

Although it seemed improbable when the Mini was released in 1959 as a small, utilitarian economy car, the performance potential proved extraordinary; in rallies and on race tracks it was a first-rate competitor for over a decade, remaining popular in many forms of competition to this day. The joint venture with the Formula One constructor Cooper provided the basis for most of the success but by far the most intriguing possibility for more speed was the model which was never developed beyond the prototype stage: the twin-engined Twini.

It wasn’t actually a novel approach. BMC, inspired apparently by English racing driver Paul Emery (1916–1993) who in 1961 had built a twin-engined Mini, used the Mini’s underpinnings to create an all-purpose cross-country vehicle, the Moke, equipped with a second engine and coupled controls which, officially, was an “an engineering exercise” but had actually been built to interest the Ministry of Defence in the idea of a cheap, all-wheel drive utility vehicle, so light and compact it could be carried by small transport aircraft and serviced anywhere in the world. The army did test the Moke and were impressed by its capabilities and the flexibility the design offered but ultimately rejected the concept because the lack of ground-clearance limited the terrain to which it could be deployed. Based on the low-slung Mini, that was one thing which couldn’t easily be rectified. Instead, using just a single engine in a front-wheel-drive (FWD) configuration, the Moke was re-purposed as a civilian model, staying in production between 1964-1989 and offered in various markets. Such is the interest in the design that several companies have resumed production, including in electric form and it remains available today.

Cutaway drawing of Cooper’s Twini.

John Cooper (1923-2000), aware of previous twin-engined racing cars, had tested the prototype military Moke and immediately understood the potential the layout offered for the Mini (ground clearance not a matter of concern on race tracks) and within six weeks the Cooper factory had constructed a prototype. To provide the desired characteristics, the rear engine was larger and more powerful, the combination, in a car weighing less than 1600 lb (725 kg), delivering a power-to-weight ratio similar to a contemporary Ferrari Berlinetta and to complete the drive-train, two separate gearboxes with matched ratios were fitted. Typically Cooper, it was a well thought-out design. The lines for the brake and clutch hydraulics and those of the main electrical feed to the battery were run along the right-hand reinforcing member below the right-hand door while on the left side were the oil and water leads, the fuel supply line to both engines fed from a central tank. The electrical harness was ducted through the roof section and there was a central throttle link, control of the rear carburetors being taken from the accelerator, via the front engine linkage, back through the centre of the car. It sounded intricate but the distances were short and everything worked.

Twini replica.

John Cooper immediately began testing the Twini, evaluating its potential for competition and as was done with race cars in those happy days, that testing was on public roads where it proved to be fast, surprisingly easy to handle and well-balanced. Unfortunately, de-bugging wasn't complete and during one night session, the rear engine seized which resulting in a rollover, Cooper seriously injured and the car destroyed. Both BMC and Cooper abandoned the project because the standard Mini-Coopers were proving highly successful and to qualify for any sanctioned competition, at least one hundred Twinis would have to have been built and neither organization could devote the necessary resources for development or production, especially because no research had been done to work out whether a market existed for such a thing, were it sold at a price which guaranteed at least it would break even.

The concept however did intrigue others interested in entering events which accepted one-offs with no homologation rules stipulating minimum production volumes. Downton Engineering built one and contested the 1963 Targa Florio where it proved fast but fragile, plagued by an overheating rear-engine and the bugbear of previous twin-engined racing cars: excessive tire wear. It finished 27th (and last) but it did finish, unlike some of the more illustrious thoroughbreds which fell by the wayside. Interestingly, the Downton engineers choose to use a pair of the 998 cm3 (61 cubic inch) versions of the BMC A-Series engine which was a regular production iteration and thus in the under-square (long stroke) configuration typical of almost all the A-Series. The long stroke tradition in British engines was a hangover from the time when the road-taxation system was based on the cylinder bore, a method which had simplicity and ease of administration to commend it but little else, generations of British engines distinguished by their dreary, slow-revving characteristics. The long stroke design did however provide good torque over a wide engine-speed range and on road-course like the Targa Florio, run over a mountainous Sicilian circuit, the ample torque spread would have appealed more to drivers than ultimate top-end power. For that reason, although examples of the oversquare 1071 cm3 (65 cubic inch) versions were available, it was newly developed and a still uncertain quantity and never considered for installation. The 1071 was used in the Mini Cooper S only during 1963-1964 (with a companion 970 cm3 (61 cubic inch) version created for use in events with a 1000 cm3 capacity limit) and the pair are a footnote in A-Series history as the only over-square versions released for sale

Twin-engined BMW Mini (Binni?).

In the era, it’s thought around six Twinis were built (and there have been a few since) but the concept proved irresistible and twin-engined versions of the "new" Mini (built since 2000 by BMW) have been made. It was fitting that idea was replicated because what was striking in 2000 when BMW first displayed their Mini was that its lines were actually closer to some of the original conceptual sketches from the 1950s than was the BMC Mini on its debut. BMW, like others, of course now routinely add electric motors to fossil-fuel powered cars so in that sense twin (indeed, sometimes multi-) engined cars are now common but to use more than one piston engine remains rare. Except for the very specialized place which is the drag-strip, the only successful examples have been off-road or commercial vehicles and as John Cooper and a host of others came to understand, while the advantages were there to be had, there were easier, more practical ways in which they could be gained. Unfortunately, so inherent were the drawbacks that the problems proved insoluble.