Reinsure (pronounced ree-in-shoor

or ree-in-shur)

(1) In insurance, to again insure.

(2) In insurance, to insure under a contract by which a

first insurer is relieved of part or all of the risk (on which a policy has

already been issued), which devolves upon another insurer. It’s preferable in this context to use the hyphenated

re-insure to distinguish from reinsure (the again of again insuring something.

1745–55: The construct was re- + insure. The

re- prefix was from the Middle English re-, from the circa 1200 Old French re-,

from the Latin re- & red- (back; anew; again; against), from the primitive

Indo-European wre & wret- (again), a metathetic alteration

of wert- (to turn). It displaced the native English ed- & eft-. A hyphen is not

normally included in words formed using this prefix, except when the absence of

a hyphen would (1) make the meaning unclear, (2) when the word with which the

prefix is combined begins with a capital letter, (3) when the word with which

the is combined with begins with another “re”, (4) when the word with which the

prefix is combined with begins with “e”, (5) when the word formed is identical

in form to another word in which re- does not have any of the senses listed

above. As late as the early twentieth

century, the dieresis was sometimes used instead of a hyphen (eg reemerge) but

this is now rare except when demanded for historic authenticity or if there’s

an attempt deliberately to affect the archaic.

Re- may (and has) been applied to almost any verb and previously

irregular constructions appear regularly in informal use; the exceptions are all

forms of be and the modal verbs (can, should etc). Although it seems certain the origin of the

Latin re- is the primitive Indo-European wre

& wret- (which has a parallel in

Umbrian re-), beyond that it’s uncertain and while it seems always to have

conveyed the general sense of "back" or "backwards", there

were instances where the precise was unclear and the prolific productivity in Classical

Latin tended make things obscure. Insure was from the mid-fifteenth century insuren, a variant spelling of the late

fourteenth century ensuren (to

assure, give formal assurance (also the earlier (circa 1400) sense of "make

secure, make safe")) from the Anglo-French enseurer & Old French ensurer,

probably influenced by Old French asseurer

(assure), the construct being en- (make) + seur

or sur (safe, secure, undoubted). The technical meaning in commerce (make safe

against loss by payment of premiums; undertake to ensure against loss etc)

dates from 1635 and replaced assure in that sense. Reinsure, reinsured & reinsuring are verbs and reinsurer

& reinsurance are nouns; the common noun plural is reinsurances.

Reinsurance

In commerce, reinsurance is a contract of insurance an insurance

company buys from a third-party insurance company to (in whole or in part) limit

its liability in the event of against the original policy. In the industry jargon, the company purchasing

the reinsurance is called the "ceding company" (or "cedent"

or "cedant") while the issuer of the reinsurance policy is the

"reinsurer". Reinsurance can

be used for collateral purposes such as a device to conform to regulatory

capital requirements or as a form of transfer payment to maximize the

possibilities offered by international taxation arrangements purposes but the

primary purpose is as risk-management, a form of hedging in what is essentially

a high-stakes gambling market. There are

specialised reinsurance companies which, in their insurance operations, do

little but reinsurance but many general insurers also operate in the market,

their contracts sometimes layered as they reinsure risk they’re previously

assumed as reinsurance.

In the industry, there are seven basic flavors of reinsurance:

(1) Facultative coverage: This protects an insurance

provider only for an individual, or a specified risk, or contract. If there are several risks or contracts that

needed to be reinsured, each one must be negotiated separately and the reinsurer

has all the right to accept or deny a facultative reinsurance proposal. Facultative reinsurance comprises a significant

percentage of reinsurance business and must, by definition, be negotiated individually

for each policy reinsured. Facultative

reinsurance is normally purchased by a cedent for risks either not or

insufficiently covered by reinsurance treaties, for amounts above contractual

thresholds or for unusual risks.

(2) Reinsurance treaty: A treaty contract is one in

effect for a specified period of time, rather than on a per risk, or contract

basis. For the term of the contract, the

reinsurer agrees to cover all or a portion of the risks that may be have been incurred

by the cedent. Treaty reinsurance is

however just another contract and there’s no defined template; the agreement may

obligate the reinsurer to accept reinsurance of all contracts within the scope

("obligatory reinsurance”) or it may allow the insurer to choose which

risks it wants to cede, with the reinsurer obligated to accept such risks ("facultative-obligatory

reinsurance ((fac oblig)).

(3) Proportional reinsurance: Under this contract, the

reinsurer receives a pro-rated share of the premiums of all policies sold by

the cedent, the corollary being that when claims are made, the reinsurer bears

a pro-rata portion of the losses. The

two pro-rata calculations need not be the same; that a function of agreement by

contract but, in proportional reinsurance, the reinsurer will also reimburse

the cedent for defined administrative costs such as processing, business

acquisition and writing costs. The

industry jargon for this is “ceding commission” and the payment of costs can be

front-loaded (ie paid up-front).

Technically, it’s a kind of agency arrangement best thought of as

out-sourcing.

(4) Non-proportional reinsurance: Non-proportional reinsurance,

also known as “threshold policies”, permit claims against the policy to be

invoked only if the cedent’s losses exceed a specified amount (which can be defined

in the relevant currency or as a percentage) which is referred to as the priority

or retention limit. Operating something

like excess in domestic insurance, it means the does not have a proportional

share in the premiums and losses of cedent and the priority or retention limit

may be based on a single type of risk or an entire business category; this is a

matter of contractual agreement.

(5) Excess-of-Loss (EoL) reinsurance: This is a

specialised variation of non-proportional coverage, again the reinsurer covering

only losses exceeding the cedent’s retained limit but EoLs are used almost

exclusively in large-scale, high-value contracts associated with the coverage

of catastrophic events. The contracts

can cover cedent either on a per occurrence basis or for all the cumulative

losses within a specified term.

(6) Risk-attaching reinsurance: Here, all claims established

during the define term of the reinsurance will be covered, regardless of

whether the losses occurred outside the coverage period whereas no coverage

will extend to claims which originate outside the coverage period, even if the

losses occurred while the reinsurance contract is in effect. These contracts are executed generally in

specific industries where circumstances differ from the commercial mainstream.

(7) Loss-occurring coverage: A kind of brute-force coverage

where the cedent can claim against all losses that occur during the term of the

reinsurance contract, the essential aspect being when the event causing the loss

have occurred, not when the claim has been booked.

Bismarck and the Reinsurance Treaty

Although in force barely three years between 1887-1890,

the Reinsurance Treaty, a secret protocol between the German and Russian Empires,

was an important landmark in European diplomatic history, partly because of the

part it played in the intricate structure of alliances and agreements

maintained by the German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck (1815–1898; Chancellor of

the German Empire 1871-1890) but mostly because of the significance of the

circumstances in which it lapsed and the events which followed.

A typically precise Bismarkian construct, the treaty required

both parties to remain neutral were the other to become involved in a war with

a third great power, but stipulated that term would not apply (1) if Germany

attacked France or (2) if Russia attacked Austria-Hungary. Under the treaty, Germany acknowledged Bulgaria

and Eastern Rumelia as part of the Russian sphere of influence and agreed to

support Russia in (essentially any) actions it might take against the Ottoman

Empire to secure or extend hegemony in the Black Sea, the Bosporus and the

Dardanelles, the straits leading to the Mediterranean. The treaty had its origins in the sundering in

1887 of the earlier tripartite German-Austro-Hungarian-Russian (Dreikaiserbund (League of the Three

Emperors)) which had had to lapse because Vienna and St Petersburg were both anxious

to extend their spheres of interests in the Balkans as the Ottoman Empire

declined and needed to keep options open.

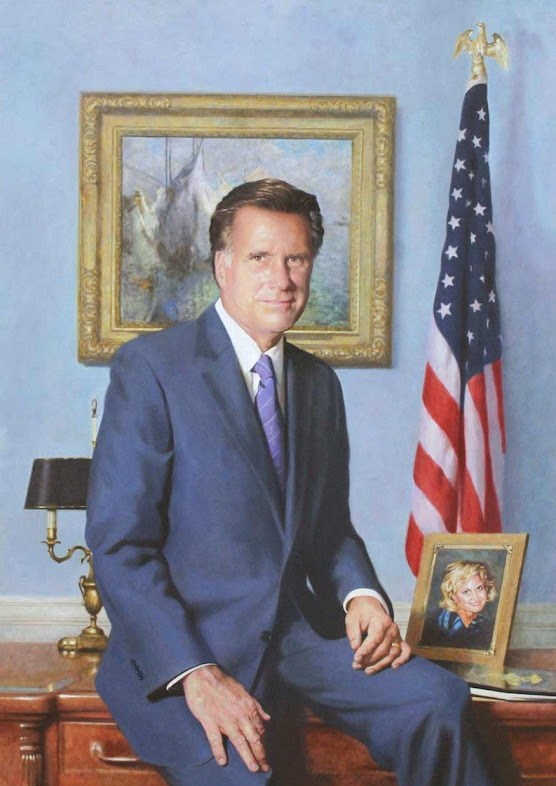

Otto von Bismark.Bismarck interlocking system of alliances was designed to

preserve peace in Europe and the spectre of a competition between Russia and

Austria–Hungary to carve up the Ottoman spoils in the Balkans, thus the

attraction of the reinsurance treaty to forestall the risk of an alliance between

St Petersburg and Paris. Ever since the

Franco-Prussian war, the cornerstone of Bismarck’s foreign policy had been the

diplomatic isolation of France, his nightmare being hostile states to the west

and east, a dynamic in Germany political thought which would last

generations. It certainly wasn’t true he

believed (as he was reputed to have said), that the Balkans weren’t worth the

death on one German soldier and that he never bothered reading the mailbag from

Constantinople, but he did think it infinitely preferable to manage what should

be low-intensity conflicts there than the threat of fighting a war on two

fronts against France and Russia. Thus

the Reinsurance Treaty which, strictly speaking, didn’t contradict the alliance

between the German and Austro-Hungarian empires, the neutrality clauses not

applying if Germany attacked France or Russia attacked Austria-Hungary.

However, Bismarck’s system was much dependent on

his skills and sense of the possible.

Once Kaiser Wilhelm II (1859–1941; German Emperor (Kaiser) and King of

Prussia 1888-1918) dismissed Bismarck in 1890, German foreign policy fell into

the hands of a sovereign who viewed the European map as a matter to be

discussed between kings and Bismarck's successor as Chancellor, Leo von Caprivi

(1831–1899; Chancellor of the German Empire 1890-1894) was inexperienced in such

matters. Indeed it was von Caprivi who,

showing a punctiliousness towards treaties one of his successors wouldn’t

choose to adopt, took seriously the contradictions with some existing

arrangements the Reinsurance Treaty at least implied and declined the Russian

request in 1890 for a renewal. From that

point were unleashed the forces which would see Russian and France drawn

together while Germany strengthened its ties to Austria-Hungry and the Ottomans

while simultaneously seeking to compete with Britain as a naval power, a threat

which would see Britain and France set aside centuries of enmity to conclude

anti-German arrangements. While the path

from the end of the Reinsurance Treaty to the outbreak of the First World War in

1914 wasn’t either inevitable or lineal, it’s not that crooked.

Reinsurance recommended: Lindsay Lohan in Esurance Sorta Mom advertisement for Esurance Insurance (an Allstate company).