Kettle (pronounced ket-l)

(1) A container (historically and still usually made of

metal) used to boil liquids or cook foods; a specialized kind of pot with a

handle & spout and thus optimized for pouring (in some markets known variously

as teakettles, jugs, electric jugs etc).

(2) By extension, a large metal vessel designed to

withstand high temperatures, used in various industrial processes such as

refining, distilling & brewing (also sometimes referred to as boilers,

steamers, vats, vessels or cauldrons).

(3) In geology, as kettle hole, a steep, bowl-shaped

hollow in ground once covered by a glacier. Kettles are believed to form when a block of

ice left by a glacier becomes covered by sediments and later melts, leaving a

hollow. They are usually dozens of

meters deep and can be dozens of kilometers in diameter, often containing

surface water.

(4) In percussion, as kettledrum (or kettle-drum), a large

hemispherical brass percussion instrument (one of the timpani) with a drumhead

that can be tuned by adjusting its tension.

There was also the now obsolete use of kettledrum to mean “an informal

social party at which a light collation is offered, held in the afternoon or

early evening”.

(5) In crowd control, a system of UK origin using an

enclosed area into which demonstrators or protesters are herded for containment

by authorities (usually taking advantage of aspects of the natural or built environment).

(6) To surround and contain demonstrators or protesters

in a kettle.

(7) In weightlifting, as kettlebell, a weight consisting

of a cast iron ball with a single handle for gripping the weight during

exercise.

(8) In ornithology, a group of raptors riding a thermal,

especially when migrating.

(9) In the slang of railroads, a steam locomotive

Pre 900: From the Middle English ketel & chetel, from the

Old English cetel & ċietel (kettle, cauldron), and possibly

influenced by the Old Norse ketill, both

from the Proto-Germanic katilaz (kettle,

bucket, vessel), of uncertain origin although etymologists find most persuasive

the notion of it being a borrowing of the Late Latin catīllus (a small pot), a diminutive of the Classical Latin catinus (a large pot, a vessel for

cooking up or serving food”), from the Proto-Italic katino but acknowledge the word may be a Germanic form which became

confused with the Latin dring the early Medieval period.. It should thus be compared with the Old

English cete (cooking pot), the Old

High German chezzi (a kettle, dish,

bowl) and the Icelandic kati & ketla (a small boat). It was cognate with the West Frisian tsjettel (kettle), the Dutch ketel (kettle), the German Kessel (kettle), the Swedish kittel (cauldron) & kittel (kettle), the Gothic katils (kettle) and the Finnish kattila. There may also be some link with the Russian

котёл (kotjól) (boiler, cauldron). Probably few activities are a common to human

cultures as the boiling of water and as the British Empire spread, the word

kettle travelled with the colonial administrators, picked up variously by the Brunei Malay (kitil),

the Hindi केतली (ketlī), the Gujarati કીટલી (kīṭlī), the Irish citeal,

the Maltese kitla and the Zulu igedlela. Beyond the Empire, the Turks adopted it

unaltered (although it appeared also as ketil). Kettle is a noun

& verb, kettled is a verb & adjective and kettling is a verb; the noun

plural is plural kettles.

The boiling of water for all sorts of purposes is an

activity common to all human societies for thousands of years so the number of

sound-formations which referred to pots and urns used for this purpose would

have proliferated, thus the uncertainty about some of the development. The Latin catinus

has been linked by some with Ancient Greek forms such as kotylē (bowl, dish) but this remains uncertain and words for many types

of vessels were often loanwords. The fourteenth

century adoption in Middle English of an initial “k” is thought perhaps to indicate

the influence of the Old Norse cognate ketill

and the familiar modern form “tea-kettle” was used as early as 1705. In percussion, the kettledrum was described

as in the 1540s (based wholly on the shape) and in geology the kettlehole (often

clipped to “kettle) was first used in 1866 to refer to “a deep circular hollow

in a river bed or other eroded area, pothole>, hence “kettle moraine” dating

from 1883 and used to describe one characterized by such features.

Lindsay Lohan cooking pasta in London, October 2014. One hint this is London rather than Los Angeles is the electric kettle to her left, a standard item in a UK kitchen but less common in the US.

In most of the English-speaking world, kettle refers usually

to a vessel or appliance used to boil water, the exception being the US where the

device never caught on to the same extent and in Australia and New Zealand, it’s

common to refer to the electric versions as “jugs”. Americans do use kettles, but they’re not as widely

used as they are in Australia, New Zealand & the UK where their presence in

a kitchen is virtually de rigueur. One

reason is said to be that in the US coffee makers & instant hot water

dispensers were historically more common, as was the use of tea bags rather

than loose-leaves to make tea. Those

Americans who have a kettle actually usually call it a “kettle” although (and

there seems to be little specific regionalism associated with this) it may also

be called a “hot pot”, “tea kettle” or “water boiler”.

In idiomatic use, the phrase “a watched kettle never

boils” has the same meaning as when used with “watched pot” and is a commentary

on (1) one’s time management and (2) one’s perception of time under certain

circumstances. The phrase “pot calling

the kettle black” is understood only if it’s realized both receptacles used to

be heated over open flames and their metal thus became discolored and

ultimately blackened by the soot & smoke. It’s used to convey an accusation of hypocrisy,

implying that an accuser is of the same behavior or trait they are criticizing

in others. The now common sense of “a

different kettle of fish” is that of something different that to which it erroneously

being compared but the original “kettle of fish” dated from circa 1715 and referred

to “a complicated and bungled affair” and etymologists note it’s not actually

based on fish being cooked in a kettle (although there was a culinary implement

called a “fish kettle” for exactly that purpose but there’s no evidence it was

used prior to 1790) but is thought to refer to “kettle” as a variant of kittle & kiddle (weir or fence with nets set in rivers or along seacoasts

for catching fish), a use dating from the late twelfth century (it appears in

the Magna Charta (1215) as the Anglo-Latin kidellus),

from the Old French quidel, probably

from the Breton kidel (a net at the

mouth of a stream).

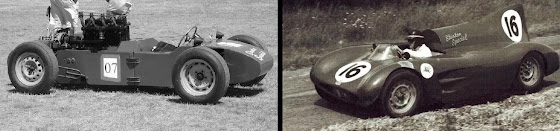

1974 Suzuki GT750 “Kettle”. The front twin disc setup was added in 1973 and was one of the first of its kind.

The Suzuki GT750 was produced between 1971-1977 and was an interesting example of the breed of large-capacity two-stroke motorcycles which provided much excitement and not a few fatalities but which fell victim to increasingly stringent emissions standards and the remarkable improvement in the performance, reliability and refinement of the multi-cylinder four-stroke machines. Something of a novelty was the GT750 was water-cooled, at the time rarely seen although that meant it missed out on one of Suzuki’s many imaginative acronyms: the RAC (ram air cooling) used on the smaller capacity models. RAC was a simple aluminum scoop which sat atop the cylinder head and was designed to optimize air-flow. It was the water-cooling of the GT750 which attracted nicknames but, a generation before the internet, the English language tended still to evolve with regional variations so in England it was “the Kettle”, in Australia “the Water Bottle” and in North America “the Water Buffalo”. Foreign markets also went their own way, the French favoring “la bouillotte” (the hot water bottle) and the West Germans “Wasserbüffel” (water buffalo). Suzuki called those sold in North America the "Le Mans" while RoW (rest of the world) models were simply the "GT750".

Detail of the unusual 4-3 system: The early version with the ECTS (left), the bifurcation apparatus for the central cylinder's header (centre) and the later version (1974-1977) without the ECTS (right). Motorcyclists have long had a fascination with exhaust systems.

The GT750 shared with the other three-cylinder Suzukis (GT380 & GT550) the novelty of an unusual 4-into-3 exhaust system (the center exhaust header was bifurcated), the early versions of which featured the additional complexity of what the factory called the Exhaust Coupler Tube System (ECTS; a connecting pipe joining the left & right-side headers) which was designed to improve low-speed torque. The 4-into-3 apparently existed for no reason other than to match the four-pipe appearance on the four stroke, four cylinder Hondas and Kawasakis, an emulation of the asymmetric ducting used on Kawasaki's dangerously charismatic two-strokes presumably dismissed as "to derivative".

Kettling is now familiar as a method of large-scale crowd control in which the authorities assemble large cordons of police officers which move to contain protesters within a small, contained space, one often chosen because it makes use of the natural or built environment. Once contained, demonstrators can selectively be detained, released or arrested. It’s effective but has been controversial because innocent bystanders can be caught in its net and there have been injuries and even deaths. Despite that, although courts have in some jurisdictions imposed some restrictions on the practice, as a general principle it remains lawful to use in the West. The idea is essentially the same as the military concept of “pocketing”, the object of which was, rather than to engage the enemy, instead to confine them to a define area in which the only route of escape was under the control of the opposing force. The Imperial Russian Army actually called this the котёл (kotyol or kotyel) which translated as cauldron or kettle, the idea being that (like a kettle), it was “hot” space with only a narrow aperture (like a spout) through which the pressure could be relieved.

David Low’s (1891-1963) cartoon (Daily Express, 31 July 1936) commenting on one of the many uncertain aspects of British foreign policy in the 1930s; Left to right: Thomas Inskip (1876–1947), John Simon (1873–1954), Philip Cunliffe-Lister (1884–1972), Duff Cooper (1890–1954), Samuel Hoare (1880–1959), Neville Chamberlain (1869–1940; UK prime-minister 1937-1940), Stanley Baldwin (1867–1947; UK prime-minister 1923-1924, 1924-1929 & 1935-1937) & Anthony Eden (1897-1977; UK prime-minister 1955-1957).

Low attached “trademarks” to some of those he drew. Baldwin was often depicted with a sticking plaster over his lips, an allusion to one of his more infamous statements to the House of Commons in which he said “…my lips are sealed”. Sir John Simon on this occasion had a kettle boiling on his head, a fair indication of his state of mind at the time.

About to explode: Low’s techniques have on occasion been borrowed and some cartoonist might one day be tempted to put a boiling kettle on the often hot-looking head of Barnaby Joyce (b 1967; thrice (between local difficulties) deputy prime minister of Australia 2016-2022). Malcolm Turnbull (b 1954; prime-minister of Australia 2015-2018), a student of etymology, was as fond as those at The Sun of alliteration and when writing his memoir (A Bigger Picture (2020)) he included a short chapter entitled "Barnaby and the bonk ban". As well as the events which lent the text it's title, the chapter was memorable for his inclusion of perhaps the most vivid thumbnail sketch of Barnaby Joyce yet penned:

"Barnaby is a complex, intense, furious personality. Red-faced, in full flight he gives the impression he's about to explode. He's highly intelligent, often good-humoured but also has a dark and almost menacing side - not unlike Abbott (Tony Abbott (b 1957; prime-minister of Australia 2013-2015)) - that seems to indicate he wrestles with inner troubles and torments."

Kettle

logic

The term “Kettle

logic” (originally in the French: la

logique du chaudron) was coined by French philosopher Jacques Derrida

(1930-2004), one of the major figures in the history of post-modernist thought,

remembered especially for his work on deconstructionism. Kettle logic is category of rhetoric in which

multiple arguments are deployed to defend a point, all with some element of

internal inconsistency, some actually contradictory. Derrida drew the title from the “kettle-story”

which appeared in two works by the founder of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud

(1856-1939): The Interpretation of Dreams

(1900) & Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious (1905). In his analysis of “Irma's dream”, Freud

recounted the three arguments offered by the man who returned in damaged

condition a kettle he’d borrowed.

(1) That the

kettle had been returned undamaged.

(2) That the

kettle was already damaged when borrowed.

(3) That the

kettle had never been borrowed.

The three

arguments are inconsistent or contradictory but only one need be found true for

the man not to be guilty of causing the damage.

Kettle logic was used by Freud to illustrate the way it’s not unusual

for contradictory opposites simultaneously to appear in dreams and be

experienced as “natural” in a way would obviously wouldn’t happen in a

conscious state. The idea is also analogous

with the “alternative plea” strategy used in legal proceedings.

In US law, “alternative

pleading” is the legal strategy in which multiple claims or defenses (that may

be mutually exclusive, inconsistent or contradictory) may be filed. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, at

the point of filing the rule is absolute and untested; a party may thus file a

claim or defense which defies the laws of physics or is in some other way technically

impossible. The four key aspects of alternative

pleading are:

(1) Cover All

Bases: Whatever possible basis might be available in a statement of claim or defence

should be invoked to ensure that if a reliance on one legal precept or theory

fails, others remain available. Just because

a particular claim or defense has been filed, there is no obligation on counsel

to pursue each.

(2) Multiple

Legal Fields: A party can plead different areas of law are at play, even if

they would be contradictory if considered together. A plaintiff might allege a defendant is

liable under both breach of contract and, alternatively, unjust enrichment if

no contract is found afoot.

(3) Flexibility: Alternative pleading interacts with the “discovery process” (ie going through each other’s filing cabinets and digital storage) in that it makes maximum flexibility in litigation, parties able to take advantage of previously unknown information. Thus, pleadings should be structured not only on the basis of “known knowns” but also “unknown unknowns”, “known unknowns” and even the mysterious “unknown knowns”. He may have been evil but for some things, we should be grateful to Donald Rumsfeld (1932–2021: US defense secretary 1975-1977 & 2001-2006).

(4) No Admission of Facts: By pleading in the alternative, a party does not admit that any of the factual allegations are true but are, in effect, asserting if one set of facts is found to be true, then one legal theory applies while if another set is found to be true, another applies. This is another aspect of flexibility which permits counsel fully to present a case without, at the initial stages of litigation, being forced to commit to a single version of the facts or a single legal theory.

In the US, alternative pleading (typically wordy (there was a time when in some places lawyers charged “per word” in documents), lawyers prefer “pleading in the alternative”) generally is permitted in criminal cases, it can manifest as a defendant simultaneously claiming (1) they did not commit alleged act, (2) at the time the committed the act they were afflicted by insanity they are, as a matter of law, not criminally responsible, (3) that at the time they committed the act they were intoxicated and thus the extent of their guilt is diminished or (4) the act committed way justified by some reason such as provocation or self defense. Lawyers however are careful in the way the tactic is used because judges and juries can be suspicious of defendants claiming the benefits of both an alibi and self defense.