Sabot (pronounced sab-oh or sa-boh (French)

(1) A

shoe made of a single block of wood hollowed out, worn especially by farmers

and workers in the Netherlands, France, Belgium etc.

(2) A

shoe with a thick wooden sole and sides and a top of coarse leather.

(3) In

military ordinance, a wooden or metal disk formerly attached to a projectile in

a muzzle-loading cannon.

(4) In

firearm design, a lightweight sleeve in which a sub-caliber round is enclosed

in order to make it fit the rifling of a firearm; after firing the sabot drops

away.

(5) In

nautical use, a small sailing boat with a shortened bow (Australia).

1600–1610: From the French sabot, from the Old French çabot, a blend of savate (old shoe), of uncertain origin and influenced by bot (boot). The mysterious French savate (old shoe), despite much research by etymologists, remains of unknown origin. It may be from the Tatar чабата (çabata) (overshoes), ultimately either from the Ottoman Turkish چاپوت (çaput or çapıt) (patchwork, tatters), or from the Ottoman Turkish چاپمق (çapmak) (to slap on), or of Iranian origin, cognate with the modern Persian چپت (čapat) (a kind of traditional leather shoe). It was akin to the Old Provençal sabata, the Italian ciabatta (old shoe), the Spanish zapato, the Norman chavette and the Portuguese sapato. The plural is sabots.

Young women in clogs, smoking cigarettes.

Sabot is the ultimate source of sabotage & saboteur. English picked up sabotage from the French saboter (deliberately to damage, wreck or botch), used originally to refer to the tactic used in industrial disputes by workers wearing the wooden shoes called sabots who disrupted production in various ways. The persistent myth is that the origin of the term lies in the practice of workers throwing the wooden sabots into factory machinery to interrupt production but the tale appears apocryphal, one account even suggesting sabot-clad workers were simply considered less productive than others who had switched to leather shoes, roughly equating the term sabotage with inefficiency.

Vintage Dutch sabots.

The words saboter and saboteur appear first to have appeared in French dictionaries in 1808 (Dictionnaire du Bas-Langage ou manières de parler usitées parmi le peuple of d'Hautel) suggesting there must have been some use of the words in printed materials some time prior to then. The literal definition provided was “to make noise with sabots” and “bungle, jostle, hustle, haste” but with no suggestion of the shoes being used in the “spanner in the works” sense suggested by the myth. Sabotage would not appear in dictionaries for some decades, noted first in the Dictionnaire de la langue française of Émile Littré (1801-1881) published between 1873-1874 and curiously, it’s defined as referencing that specialty of cobbling “the making of sabots; sabot maker”. It wouldn’t be until 1897 that the use to describe malicious damage in pursuit of industrial or political aims was recorded, anarcho-syndicalist Émile Pouget (1860-1931) publishing Action de saboter un travail (Sabotaging or bungling at work) in Le Père Peinard, which he helpfully expanded in 1911 in the user manual Le Sabotage. In neither work however was there mention of using sabots as a means of damaging or halting machinery, the sense was always of things done by those wearing sabots, the word a synecdoche for the industrial proletariat. Contemporary English-language sources confirm this. In its January 1907 edition, The Liberty Review noted sabotage was a means of “scamping work… a device… adopted by certain French workpeople as a substitute for striking. The workman, in other words, purposes to remain on and to do his work badly, so as to annoy his employer's customers and cause loss to his employer”.

Clog promotion, H&M catalog 2011.

(1) To hinder or obstruct with thick or sticky matter;

choke up.

(2) To crowd excessively, especially so that movement is

impeded; overfill.

(3) To encumber; hamper; hinder.

(4) To become clogged, encumbered, or choked up.

(5) A shoe or sandal with a thick sole of wood, cork,

rubber, or the like; a similar but lighter shoe worn in the clog dance.

(6) A heavy block, as of wood, fastened to a person or

beast to impede movement.

(7) As clog dance, a type of dance which specifically

demands the wearing of clogs.

(8) In British dialectal use, a thick piece of wood (now

rare).

(9) In the slang of association football (soccer), to

foul an opponent (now rare).

(10) A heavy block, especially of wood, fastened to the

leg of a person or animal to impede motion.

(11) To use a mobile phone to take a photograph of

(someone) and upload it without their knowledge or consent, the construct being

c(amera) + log, a briefly used term from the early days of camera-equipped

phones on the which never caught on.

1300s: Of unknown origin, most likely from the Middle English clogge (weight attached to the leg of an animal to impede movement) or from a North Germanic form such as klugu & klogo (knotty tree log) from the Old Norse, the Dutch klomp or the Norwegian klugu (knotty log of wood). The word was also used in Middle English to describe big pieces of jewelry and large testicles. The meaning "anything that impedes action" is from the 1520s, via the notion of "block or mass constituting an encumbrance” although it became nuanced, by 1755 builders were distinguishing between things clogged with whatever naturally belonged then and becoming “choked up with extraneous matter”, a distinction doubtlessly of great significance to plumbers. The sense of the "wooden-soled shoe" is attested from the late fourteenth century, used as overshoes until the introduction of rubber soles circa 1840. Related forms include the adjective cloggy, the noun clogginess, the verbs clogged & clog·ging and the adverb cloggily. A frequently used adjectival derivative is anticlogging, often as a modifier of agent and, unsurprisingly, the verb unclog, first noted circa 1600, is also common.

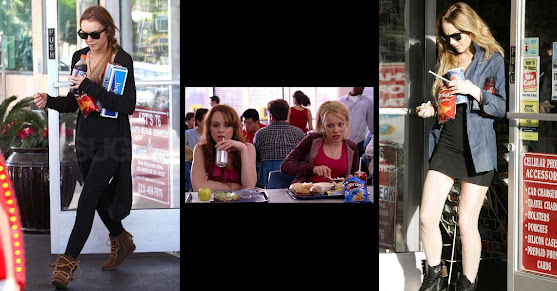

Lindsay Lohan in Gucci Black Patent Leather Hysteria Platform Clogs with wooden soles, Los Angeles, 2009. The car is a 2009 (fifth generation) Maserati Quattroporte leased by her father.

Clogs were originally made entirely of wood (hence the name), the more familiar modern form with leather uppers covering the front being noted first in the late sixteenth century but may have been worn earlier. Long popular with men working in kitchens (always with a rubber covering on the sole), the first revival as a fashion item occurred circa 1970, primarily for women and clog-dancing, a form "which required the wearing of clogs" is attested from 1863. There are now a variety of variations on the clog sole including the Tengu geta, having a single tooth in the centre and the Albarcas which features extensions something like a three-legged stool. None look very comfortable but their users appear content.

Lindsay Lohan's promotion for the collaboration between German fashion house MCM & Crocs, introducing the "pragmatic" Mega Crush Clog. Not that there was ever much doubt but now we know clogs can be "pragmatic".