Kitsch (pronounced kich)

(1) Something though tawdry in design or appearance; an

object created to appeal to popular sentiment or undiscriminating tastes,

especially if cheap (and thus thought a vulgarity).

(2) Art, decorative objects and other forms of

representation of dubious artistic or aesthetic value (many consider this

definition too wide).

1926: From the German kitsch

(literally “gaudy, trash”), from the dialectal kitschen (to coat; to smear) which in the nineteenth century was

used (as a German word) in English in art criticism describe a work as “something

thrown together”. Among “progressive” critics,

there was a revival in the 1930s to contrast anything thought conservative or

derivative with the avant garde. The

adjective kitchy was first noted in 1965 though it may earlier have been in

oral use; the noun kitchiness soon followed. Camp is sometimes used as a synonym

and the two can be interchangeable but the core point of camp is that it

attributes seriousness to the trivial and trivializes the serious. Technically, the comparative is kitscher and the

superlative kitschest but the more general kitschy is much more common. The alternative spelling kitch is simply a

mistake and was originally 1920s slang for “kitchen” the colloquial shortening dating

from 1919. Kitsch & kitchiness are nouns,

kitschify, kitschifying & kitschified are verbs and kitschy & kitchlike are adjectives; the noun plural is kitsch (especially collectively) or kitsches. Kitschesque is non-standard.

For something that lacks an exact definition, the concept of kitsch seems well-understood although not all would agree on what

objects are kitsch and what are not. Nor is there always a sense about it of a self-imposed exclusionary rule;

there are many who cherish objects they happily acknowledge are kitsch. As a general principle, kitsch is used to

describe art, objects or designs thought to be in poor taste or overly sentimental. Objects condemned as kitsch are often mass-produced,

clichéd, gaudy (the term “bling” might have been invented for the kitsch) or

cheap imitations of something. It can take some skill to adopt the approach but other items which can be part of the motif include rotary dial phones ("retro" can be a thing which transcends kitsch) and three ceramic ducks "flying" up the wall (although when lava lamps were in vogue, lava lamp buyers probably already thought them kitsch).

Lindsay Lohan: Prom Queen scene in Mean Girls (2004). If rendered in precious metal and studded with diamonds a tiara is not kitsch but something which is the same design but made with anodized plastic and acrylic rhinestones certainly is.

The Nazi regime devoted much attention to spectacle and representational architecture & art was a particular interest of Adolf Hitler (1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head of state 1934-1945). Hitler in his early adulthood had been a working artist, earning a modest living from his brush while living in Vienna in the years before World War I (1914-1918) and his landscapes and buildings were, if lifeless and uninspired, executed competently enough to attract buyers. He was rejected by the academy because he could never master a depiction of the human form, his faces especially lacking, something which has always intrigued psychoanalysts, professional and amateur. Still, while his mind was completely closed to any art of which he didn’t approve, he was genuinely knowledgeable about many schools of art and better than many he knew what was kitsch. However, the nature of the “Führer state” meant he had to see much of it because the personality cult built around him encouraged a deluge of Hitler themed pictures, statuettes, lampshades, bedspreads, cigarette lighters and dozens of other items. A misocapnic non-smoker, he ordered a crackdown on things like ashtrays but generally the flow of kitsch continued unabated until the demands of the wartime economy prevailed.

To the Berghof, his alpine headquarters on the Bavarian Obersalzberg near Berchtesgaden, Barvaria, there were constant deliveries of things likes cushions embroidered with swastikas in which would now be called designer colors and more than one of his contemporaries in their memoirs recorded that the gifts sometimes would be accompanied by suggestive photographs and offers of marriage. Truly that was “working towards the Führer”. At the aesthetic level he of course didn't approve but appreciated the gesture although they seem never to have appeared in photographs of the house’s principle rooms, banished to places like the many surrounding buildings including the conservatory of Hans Wichenfeld (the chalet on which the Berghof was based).

Hitler's study in the Berghof with only matched cushions (left) and the conservatory (centre & right) with some pillowshams (embroidered with swastikas and the initials A.H.).

In the US, Life magazine in October 1939 (a few weeks after the Nazis had invaded Poland) published a lush color feature focused on Hitler’s paintings and the Berghof, the piece a curious mix of what even then were called “human-interest stories”, political commentary and artistic & architectural criticism. One heading :“Paintings by Adolf Hitler: The Statesman Longs to Be an Artist and Helps Design His Mountain Home” illustrates the flavor but this was a time before the most awful aspects of Nazi rule were understood and Life’s editors were well-aware a significant proportion of its readership were well disposed towards Hitler’s regime. Still, there was some wry humor in the text, assessing the Berghof as possessing the qualities of a “…combination of modern and Bavarian chalet” styles, something “awkward but interesting” while the interiors, “…designed and decorated with Hitler’s active collaboration, are the comfortable kind of rooms a man likes, furnished in simple, semi-modern, sometimes dramatic style. The furnishings are in very good taste, fashioned of rich materials and fine woods by the best craftsmen in the Reich.” Life seemed to be most taken with the main stairway leading up from the ground floor which was judged “a striking bit of modern architecture.” Whether or not the editors were aware Hitler thought “modern architecture” suitable only for factories, warehouses and such isn’t clear. They also had fun with what hung on the walls, noting: “Like other Nazi leaders, Hitler likes pictures of nudes and ruins” but anyway concluded that “in a more settled Germany, Adolf Hitler might have done quite well as an interior decorator.” There was no comment on the Führer’s pillows and cushions.

Whatever Life’s views on him as interior decorator, decades later, his architect was prepared to note the dictator’s “beginner’s mistakes” as designer. In Erinnerungen (Memories or Reminiscences), published in English as Inside the Third Reich (1969)), Albert Speer (1905–1981; Nazi court architect 1934-1942; Nazi minister of armaments and war production 1942-1945) recalled:

“A huge picture window in the living room, famous for its size and the fact that it could be lowered, was Hitler s pride. It offered a view of the Untersberg, Berchtesgaden, and Salzburg. However, Hitler had been inspired to situate his garage underneath this window; when the wind was unfavorable, a strong smell of gasoline penetrated into the living room. All in all, this was a ground plan that would have been graded D by any professor at an institute of technology. On the other hand, these very clumsinesses gave the Berghof a strongly personal note. The place was still geared to the simple activities of a former weekend cottage, merely expanded to vast proportions.”

He commented also on the pillowshams: “The furniture was bogus old- German peasant style and gave the house a comfortable petit-bourgeois look. A brass canary cage, a cactus, and a rubber plant intensified this impression. There were swastikas on knickknacks and pillows embroidered by admiring women, combined with, say, a rising sun or a vow of "eternal loyalty." Hitler commented to me with some embarrassment: "I know these are not beautiful things, but many of them are presents. I shouldn't like to part with them."

The gush was also trans-Atlantic. William George Fitz-Gerald (circa 1870-1942) was a prolific Irish journalist who wrote under the pseudonym Ignatius Phayre and the English periodical Country Life published his account of a visit to the Berchtesgaden retreat on the invitation of his “personal friend” Adolf Hitler. The idea of Hitler having a "friend" (as the word conventionally is understood) is not plausible but that an invitation was extended might in the circumstances have been though is unexceptional. Although when younger, Fitz-Gerald’s writings had shown some liberal instincts, by the “difficult decade” of the 1930s, experience seems to have persuaded him the world's problems were caused by democracy and the solution was an authoritarian system, headed by what he called “the long looked for leader.” Clearly taken by his contributor’s stance, in introducing the story, Country Life’s editor called Hitler “one of the most extraordinary geniuses of the century” and noted “the Führer is fond of painting in water-colours and is a devotee of Mozart.”

Substantially,

the piece in Country Life also appeared in the journal Current History with the

title: Holiday

with Hitler: A Personal Friend Tells of a Personal Visit with Der Führer — with

a Minimum of Personal Bias”.

In hindsight it may seem a challenge for a journalist, two years on from

the regime’s well-publicized murders of probably hundreds of political opponents (and some unfortunate bystanders who would now be classed as “collateral damage”)

in the pre-emptive strike against the so-called “Röhm putsch”, to keep bias about the Nazis to a minimum although many

in his profession did exactly that, some notoriously. It’s doubtful Fitz-Gerald visited the Obersalzberg

when he claimed or that he ever met Hitler because his story is littered with minor technical errors and absurdities

such as Der Führer personally welcoming

him upon touching down at Berchtesgaden’s (non-existent) aerodrome or the loveliness

of the cherry orchid (not a species to survive in alpine regions). Historians have concluded the piece was assembled

with a mix of plagiarism and imagination, a combination increasingly familiar

since the internet encouraged its proliferation. Still, with the author assuring his readers

Hitler was really more like the English country gentlemen with which they were

familiar than the frightening and ranting “messianic” figure he was so often portrayed, it’s

doubtful the Germans ever considered complaining about the odd deviation from

the facts and just welcomed the favourable publicity.

As a "cut & paste" working journalist used to editing details so he could sell essentially the same piece to several different publications, he inserted and deleted as required, Current History’s subscribers spared the lengthy descriptions of the Berghof’s carpets, curtains and furniture enjoyed by Country Life’s readers who were also able to learn of the food severed at der Tabellenführer, (the leader's table) the Truite saumonée à la Monseigneur Selle (salmon trout Monseigneur style) and caneton à la presse (pressed duck) both praised although in all the many accounts of life of the court circle’s life on the Obersalzberg, there no mention of the vegetarian Hitler ever having such things on the menu.

Fitz-Gerald was though skilled at his craft and interpolated enough that was known to be true or at least plausible to paint a veneer of authenticity over the whole. Of the guests he reported: (1) Hitler’s long-time German-American acquaintance & benefactor (when speaking of Hitler, both better words than "friend") Ernst "Putzi" Hanfstaengl (1887–1975 and a one-time friend of Franklin Delano Roosevelt (FDR, 1882–1945, US president 1933-1945) was a fine piano player (which nobody ever denied), (2) that Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893–1946; Nazi foreign minister 1938-1945) was a wine connoisseur (he entered the wine business after marrying into the Henkell family’s Wiesbaden business although his mother-in-law remained mystified, remarking of his career in government it was: “curious my most stupid son-in-law should have turned out to be the most successful” and (3) that Dr Joseph Goebbels (1897-1975; Nazi propaganda minister 1933-1945) was an engaging dinner companion and a “droll raconteur” (it is true Goebbels’ cynicism and cruel wit could be amusing even to those appalled by his views, something like the way one didn’t have to agree with the press baron Lord Beaverbrook (Maxwell Aitken, 1879-1964) to enjoy his tart cleverness). Much of the credibility was however sustained by it being so difficult for most to “check the facts” and few would have been able to find out that in the spring of 1936 when Fitz-Gerald claimed to be enjoying the Führer’s hospitality, the quaint old Haus Wachenfeld was part of a vast building site, the place being transformed into the sprawling Berghof, the whole area unliveable and far from the idyllic scene portrayed.

Dutifully, Hitler acknowledged the many paintings which which were little more than regime propaganda although the only works for which he showed any real enthusiasm were those which truly he found beautiful. However, he knew there was a place for the kitsch… for others. In July 1939, while being shown around an exhibition staged in Munich called the “Day of German Art”, he complained to the curator that some German artists were not on display and after being told they were “in the cellar”, demanded to know why. The only one with sufficient strength of character to answer was Frau Gerhardine "Gerdy" Troost (1904–2003), the widow of the Nazi’s first court architect Paul Troost (1878–1934) and one of a handful of women with whom Hitler was prepared to discuss anything substantive. “Because it’s kitsch” she answered. Hitler sacked the curatorial committee and appointed his court photographer (Heinrich Hoffmann (1885–1957)) to supervise the exhibition and the depictions of happy, healthy peasants and heroic nude warriors returned. Hitler must have been satisfied with Herr Hoffman's selections because in November that year he conferred on him the honorific "professor", a title he would award about as freely as he would later create field marshals.

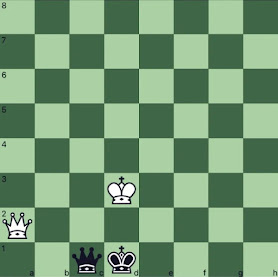

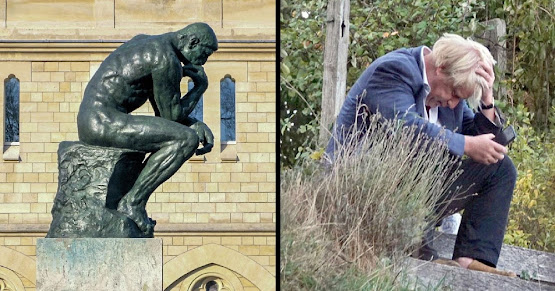

Kitsch: One knows it when one sees it.

What is kitsch will be obvious to some while others will

remain oblivious and the disagreements will happen not only at the

margins. Although there will be

sensitive souls appalled at the notion, it really is something wholly subjective

and the only useful guide is probably to borrow and adapt the threshold test for

obscenity coined by Justice Potter Stewart (1915–1985; associate justice of the

US Supreme Court 1958-1981) in Jacobellis v Ohio (1964):

I shall not today attempt further to define the kinds of material I understand to be embraced within that shorthand description and perhaps I could never succeed in intelligibly doing so. But I know it when I see it…

What makes something defined (or re-defined) as kitsch is thus a construct of factors including artistic merit (most obviously when lacking), the price tag and the social or political circumstances of the time. When Paul Émile showed Matinée de Septembre at the Paris Salon of 1912, it did not attract much comment, female nudes having for decades been a common sight in the nation’s galleries (although there had been a legislative crackdown on low-cost commercial products, presumably on the basis that while the “educated classes” could appreciate nudes in art, working class men ogled naked women merely for titillation). In other words, Parisian salon-goers had seen it all before and Matinée de Septembre, while judged competently executed, was in no way compelling or exceptional. The work may thus have been relegated to an occasional footnote in the history of art were it not for the reaction in Chicago when a reproduction appeared in the street-front window of a photography store. Reflecting the contrasting aspirations of those Europeans who first settled in the continent, in the US there has always been a tension between Puritanism and Libertarianism and one of the distinguishing characteristics of the USSC (US Supreme Court) is that it has, over centuries, sometimes imperfectly, managed usually to interpret the constitution in a way which straddles these competing imperatives with rulings cognizant of what prevailing public opinion will accept and while the judges weren’t required to rule on the matter of Matinée de Septembre’s appearance in a shop window, the brief furore was an example of one of the country’s many moral panics.

Although at first instance a jury found the work not obscene and thus fit for public view, local politicians quickly responded and found a way to ensure such things were restricted to art galleries and museums, places less frequented by those “not of the better classes”. The notoriety gained from becoming a succès de scandale (from the French and literally “success from scandal”) made it one of the best-known paintings in the US and, not being copyrighted, widely it was reproduced in prints, on accessories and parodied in what would now be called memes. The popularity however meant a re-assessment of the artistic merit and many critics dismissed it as “mere kitsch” although it was in 1957 donated to New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art where it has on occasion been hung as well as being loaned to overseas institutions. The Met placed it in storage in 2014 and while that’s not unusual, whether the decision was taken because of it’s the depiction of one so obviously youthful isn’t clear. The artist claimed his model was at the time aged 16 (thus some two years older than the star-cross’d lover in William Shakespeare’s (1564–1616) Romeo and Juliet (1597) and half a decade older than the girl who appeared on the cover of Blind Faith’s one-off eponymous album (1969)) but there is now heightened sensitivity to such depictions.

Kitsch also has a history also of becoming something else. As recently as the 1970s, tea-towels, placemats, oven mitts, tea-trays and plenty else in the West was available adorned with depictions of indigenous peoples, often as racist tropes or featuring the appropriation of culturally sensitive symbols. These are now regarded as kitsch only historically and have been re-classified as examples variously (depending on the content) of cultural insensitivity or blatant racism.

Kitsch at work: Lava Lamps and Random Number Generation

Some may have dismissed the Lava Lamp as "kitsch" but the movement of the blobs possesses properties which have proved useful in a way their inventor could never have anticipated. The US-based Cloudflare is a “nuts & bolts” internet company which provides various services including content delivery, DNS (Domain Name Service), domain registration and cybersecurity; in some aspects of the internet, Cloudflare’s services underpin as many as one in five websites so when Cloudflare has a problem, the world has a problem. For many reasons, the generation of truly random numbers is essential for encryption and other purposes but to create them continuously and at scale is a challenge. It’s a challenge even for home decorators who want a random pattern for their tiles, their difficulty being that however a large number of tiles in two or more colors are arranged, more often than not, at least one pattern will be perceived. That doesn’t mean the tiles are not in a random arrangement, just that people’s expectation of “randomness” is a shape with no discernible pattern whereas in something like a floor laid with tiles, in a random distribution of colors, it would be normal to see patterns; they too are a product of randomness in the same way there’s no reason why if tossing a coin ten times, it cannot all ten times fall as a head. What interior decorators want is not necessarily randomness but a depiction of randomness as it exists in the popular imagination.

For most purposes, computers can be good enough at generating random numbers but in the field of cryptography, they’re used to create encryption keys and the concern is that what one computer can construct, another computer might be able to deconstruct because both digital devices are working in ways which are in some ways identical. For this reason, using a machine alone has come to be regarded as a Pseudo-Random Number Generator (PRNG) simply because they are deterministic. A True Random Number Generator (TRNG) uses something genuinely random and unpredictable and this can be as simple as the tiny movements of the mouse in a user’s hand or elaborate as a system of lasers interacting with particles.

One of Cloudflare’s devices encapsulating unpredictability (and thus randomness) is an installation of 100 lava lamps, prominently displayed on a wall in their San Francisco office. Dubbed Cloudflare’s “Wall of Entropy”, it uses an idea proposed as long ago as 1996 which exploited the fluid movements in an array of lava lamps being truly random; as far as is known, it remains impossible to model (and thus predict) the flow. What Cloudflare does is every few milliseconds take a photograph of the lamps, the shifts in movement converted into numeric values. As well as the familiar electrical mechanism, the movement of the blobs is influenced by external random events such as temperature, vibration and light, the minute variations in each creating a multiplier effect which is translated into random numbers, 16,384 bits of entropy each time.

The arrangement of colors which avoids any two being together, in the horizontal or vertical, was a deliberate choice rather than randomness although, there's no reason why, had the selection truly been random, this wouldn't have been the result. Were there an infinite number of Walls of Entropy, every combination would exist including ones which avoid color paring and ones in which the colors are clustered to the extent of perfectly matching rows, colums or sides. What Cloudflare have done in San Francisco is make the lamps conform to the popular perception of randomness and that's fine because the colors have no (thus far observed) effect on the function. In art and for other purposes, what's truly random is sometimes modified so it conforms to the popular idea of randomness.