Velvet (pronounced vel-vit)

(1) A fabric fashioned from silk with a thick, soft pile

formed of loops of the warp thread either cut at the outer end or left uncut.

(2) In modern use, a fabric emulating in texture and

appearance the silk original and made from nylon, acetate, rayon etc, sometimes

having a cotton backing.

(3) Something likened to the fabric velvet, an allusion

to appearance, softness or texture,

(4) The soft, deciduous covering of a growing antler.

(5) In informal use (often as “in velvet” or “in the

velvet”), a very pleasant, luxurious, desirable situation.

(6) In slang, money gained through gambling; winnings (mostly

US, now less common).

(7) In financial trading, clear gain or profit,

especially when more than anticipated; a windfall profit.

(8) In mixology, as “Black Velvet”, a cocktail of champagne

& stout (also made with dark, heavy beers).

(9) A female chinchilla; a sow.

(10) An item of clothing made from velvet (in modern use

also of similar synthetics).

(11) In drug slang, the drug dextromethorphan.

(12) To cover something with velvet; to cover something

with something of a covering of a similar texture.

(13) In cooking, to coat raw meat in starch, then in oil,

preparatory to frying.

(14) To remove the velvet from a deer's antlers.

1275–1325: From the Middle English velvet, velwet, veluet, welwet, velvette, felwet veluet & veluwet, from the Old Occitan veluet, from the Old French veluotte, from the Medieval Latin villutittus or villūtus (literally shaggy cloth), from the classical Latin villus (nap of cloth, shaggy hair, tuft

of hair), from velu (hairy) and cognate

with French velours. The Latin villus

is though probably a dialectal variant of vellus

(fleece), from the primitive Indo-European wel-no-,

a suffixed form of uelh- (to strike). Velvet is a noun, verb & adjective,

velvetlike & velvety are adjectives, velveting & velveted are verbs

& adjective; the noun plural is velvets.

The noun velveteen was coined in 1776 to describe one of first

the imitation (made with cotton rather than silk) velvets commercially to be marketed

at scale; the suffix –een was a special use of the diminutive suffix (borrowed

from the Irish –in (used also –ine) which was used to form the diminutives of

nouns in Hiberno-English). In commercial

use, it referred to products which were imitations of something rather than

smaller. The adjective velvety emerged

in the early eighteenth century, later augmented by velvetiness. In idiomatic use, the “velvet glove” implies

someone or something is being treated with gentleness or caution. When used as “iron fist in a velvet glove”, it

suggests strength or determination (and the implication of threat) behind a

gentle appearance or demeanor. “Velvet”

in general is often applied wherever the need exists to covey the idea of “to

soften; to mitigate” and is the word used when a cat retracts its claws. The adjective “velvety” can be used of anything

smooth and the choice between it and forms like “buttery”, “silky”, “creamy” etc is just a matter of the image one wishes to summon. The particular instance “Velvet Revolution” (Sametová revoluce in Czech) refers to

the peaceful transition of power in what was then Czechoslovakia, occurring

from in late 1989 in the wake of the fall of Berlin Wall. Despite being partially in the Balkans, the

transition from communism to democracy was achieved almost wholly without

outbreaks of violence (in the Balkans it rare for much of note to happen

without violence).

Ten years after: Lindsay Lohan in black velvet, London, January 2013 (left) and in pink velour tracksuit, Dubai, January 2023 (right).

The fabrics velvet and velour can look similar but they

differ in composition. Velvet

historically was made with silk thread and was characterized by a dense pile, created

by the rendering of evenly distributed loops on the surface. There are now velvets made from cotton,

polyester or other blends and its construction lends it a smooth, plush texture

appearance, something often finished with a sheen or luster. A popular modern variation is “crushed velvet”,

achieved by twisting the fabric while wet which produces a crumpled and crushed

look although the effect can be realized also by pressing the pile of fabric in

a different direction. It’s unusual in

that object with most fabric is to avoid a “crumpled” look but crushed velvet

is admired because of the way it shimmers as the light plays upon the

variations in the texture. The crushing

process doesn’t alter the silky feel because of the dense pile and the fineness

of the fibers. Velour typically is made

from knit fabrics such as cotton or polyester and is best known for its stretchiness

which makes its suitable for many purposes including sportswear and upholstery. Except in some specialized types, the pile is

less dense than velvet (a consequence of the knitted construction) and while it

can be made with a slight shine, usually the appearance tends to be matte. Velour is used for casual clothing, tracksuits

& sweatshirts and it’s hard-wearing properties mean it’s often used for upholstery

and before the techniques emerged to permit vinyl to be close to

indistinguishable from leather, it was often used by car manufacturers as a more

luxurious to vinyl. The noun velour (historically

also as velure & velours) dates from 1706 and was from

the French velours (velvet), from the

Old French velor, an alteration of velos (velvet) from the same Latin

sources as “velvet”.

US and European visions of luxury: 1974 Cadillac Fleetwood Talisman in velour (top left), 1977 Chrysler New Yorker Brougham in leather (top right), 1978 Mercedes-Benz 450 SEL 6.9 in velour (bottom left) & 1979 Mercedes-Benz 450 SEL 6.9 in leather (bottom right). Whether in velour or leather, the European approach in the era was more restrained.

In car interiors, the golden age of velour began in the US

in the early 1970s and lasted almost two decades, the increasingly plush

interiors characterized by tufting and lurid colors. Chrysler in the era made a selling point of

their “rich, Corinthian leather” but the extravagant velour interiors were both

more distinctive and emblematic of the era, the material stretching sometimes

from floor to roof (the cars were often labeled “Broughams”). The dismissive phrase used of the 1970s was “the decade style forgot” and that

applied to clothes and interior decorating but the interior designs Detroit

used on their cars shouldn’t be forgotten and while the polyester-rich cabins (at

the time too, on the more expensive models one’s feet literally could sink into

the deep pile carpet) were never the fire-risk comedians claimed, many other criticisms

were justified. Cotton-based velour had

for decades been used by the manufacturers but the advent of mass-produced, polyester

velour came at a time when “authenticity” didn’t enjoy the lure of today and

the space age lent the attractiveness of modernity to plastics and faux wood,

faux leather and faux velvet were suddenly an acceptable way to “tart up” the

otherwise ordinary. At the top end of

the market, although the real things were still sometimes used, even in that

segment soft, pillowy, tufted velour was a popular choice.

1989 Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham D'Elegance in velour (left) and a "low-rider" in velour (right). The Cadillac is trimmed in a color which in slang came to be known as "bordello red". Because of changing tastes, manufacturers no longer build cars with interiors which resemble a caricature of a mid-priced brothel but the tradition has been maintained (and developed) by the "low-rider" community, a sub-culture with specific tastes.

At the time, the interiors were thought by buyers to

convey “money” and the designers took to velour because the nature of the

material allowed so many techniques cheaply to be deployed. Compared with achieving a similar look in

leather, the cost was low, the material cost (both velour and the passing

underneath or behind) close to marginal and the designers slapped on pleats, distinctive

(and deliberately obvious) stitching and extra stuffing, the stuff covering seats,

door panels, and headliners, augmented with details like tufting (recessed) buttons, grab-handles and chrome accent pieces (often anodized plastic). By the 1980s, velour had descended to the

lower-priced product lines and this was at a time when the upper end of the

market increasingly was turning to cars from European manufacturers, notably

Mercedes-Benz and BMW, both of which equipped almost all their flagships

destined for the US market with leather and real wood although the cloth was more common in Europe.

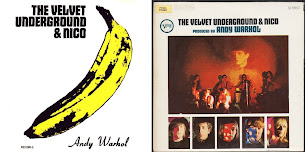

The (posthumously) influential US rock band The Velvet Underground gained their name from a book with that title, published in 1963, the year before their original formation although it wouldn’t be until 1965 the band settled on the name. The book was by journalist Michael Leigh (1901-1963) and it detailed the variety of “aberrant sexual practices” in the country and is notable as one of the first non-academic texts to explore what was classified as paraphilia (the sexual attraction to inanimate objects, now usually called Objectum Sexuality (OS) or objectum romanticism (OR) (both often clipped to "objectum")). Leigh took a journalistic approach to the topic which focused on what was done, by whom and the ways and means by which those with “aberrant sexual interests” achieved and maintained contact. The author little disguised his distaste for much about what he wrote. The rock band’s most notable output came in four albums (The Velvet Underground & Nico (1967), White Light/White Heat (1968), The Velvet Underground (1969) & Loaded (1970)) which enjoyed neither critical approval nor commercial success but by the late 1970s, in the wake of punk and the new wave, their work was acknowledged as seminal and their influence has been more enduring than many which were for most of the late twentieth century more highly regarded.