Deuterogamy (pronounced doo-tuh-rog-uh-mee or dyoo-

tuh-rog-uh-mee)

A

second marriage, (as distinct from

bigamy, as defined in law and canon law), historically after the death of the first husband or wife but now applied also in other circumstances.

1650–1660:

From the Ancient Greek deuterogamía (a second

marriage), the construct being deuteron, from the Ancient Greek δεύτερος

(deúteros) (second (of two)) +

-gamy (the suffix from the Ancient Greek γάμος (gámos) used to form nouns

describing forms of marriage (and in biology to form nouns describing forms of

fertilization). The related forms are

deuterocanonical, deuteromycete, deuteromycetes, deuteron, deuterogamist, deuteronomic and

deuteronomis.

The permitted second marriage

Deuterogamy is a lesser-known companion word of

bigamy and polygamy. Bigamy is the act

of marrying one person while in a stare of marriage with another; it can be

committed unknowingly (in rare cases even by both parties) but it committed

knowingly is a criminal offence in most jurisdictions. Polygamy

is the generic term for multiple marriages and encompasses bigamy, the word used mostly by anthropologists to describe both polygyny (having several wives) and polyandry (the predictably less common

practice of enjoying several husbands).

There’s also the synonym digamy

but it’s so easily confused with the almost homophonic bigamy it should be avoided and rendered obsolete (which it may already be).

Etymologically, deuterogamy describes merely the

act of a second marriage but in canon law it was the definitional term for a

permissible second marriage, one celebrated after the death of a first wife or

husband. Under canon law, marrying

another when one’s original partner remained alive, even if a divorce had been

granted by a civil court, was bigamy.

The only circumstances in which the church would countenance a deuteronomis

marriage when the previous partner remained alive was if a bishop was prepared

to issue a certificate of annulment which created not the legal fiction that the

marriage never existed but that it was ab initio (void at its inception) because the essential sacramental component was always missing

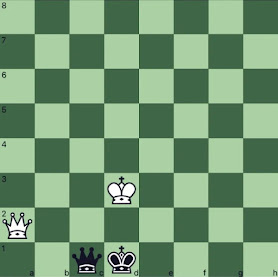

As an example, noted Roman Catholic, father of six and amateur

moral theologian Barnaby Joyce (b 1967; deputy prime-minister

of Australia thrice variously since 2016):

(1) Is an adulterer because he enjoyed intimacy with

a woman while married to another. He’s

guilty merely of single-adultery because the other woman with whom he cavorted was unmarried; had his mistress been married, double adultery would have been the offence. Surely worse.

(2) Cannot, under canon law, undertake a deuteronomis

marriage unless he can find grounds on which a bishop might be persuaded to annul

his first marriage.

All things considered, one might have thought

this difficult but in 2015, Pope Francis (b 1936; pope since 2013) issued two possibly revolutionary motu proprio (literally “on his own impulse”; essentially the law-making mechanism available

to absolute monarchs as the royal decree): Mitis iudex dominus Iesus (Reform to the Canons of the Code of

Canon that pertain to the marriage nullity cases) and Mitis et misericors Iesus (Reform of the canons of the Code of

Canons of Eastern Churches pertaining to cases regarding the nullity of marriage)

which changed canon law, simplifying the annulment process. It was a demonstration of what’s possible in

an absolute theocracy and must have induced a little envy in people like

prime-ministers dealing with bolshie cross-benchers or recalcitrant senators.

Better to help sinners consider their position, Cardinal

Francesco Coccopalmerio (b 1938; then president of the Pontifical

Council for Legislative Texts), issued a clarification, noting the Church “…does

not decree the annulment of a legally valid marriage, but rather declares the nullity

of a legally invalid marriage”. While a

piece of sophistry a bit different from what usually crosses the National Party

mind and not obviously a great deal of help, it might have been enough to give Mr Joyce hope.

"A second marriage is a triumph of hope over experience." Samuel Johnson (1709–1784).On Monday 17 January, it was announced Mr Joyce had proposed to his new partner and that she'd accepted. In a nice touch, he presented his fiancée a parti sapphire engagement ring. Parti sapphires are unique in the extraordinary way their several distinct colors simultaneously display in any light, unlike other polychromic stones which need light to fall in different ways for the range to show. The other distinction of the parti is that their value lies not in perfection but in their flaws; it's the inclusions in the parti which create the dazzling iridescence. Like Mr Joyce, the parti sapphire is loved and venerated for its flaws.

Redemption does seem much on Mr Joyce's mind. After the National Party caucus, having decided to allow hope to triumph over experience and (for the third time) elect him leader (and thus deputy prime-minister), he was gracious in victory, saying “I acknowledge my faults and I resigned as I should have and I did. I’ve spent three years on the backbench and, you know, I hope I come back a better person.” The self-identification as the prodigal son seems to draw a long theological bow and is anyway not relevant to the matters a bishop is compelled to consider when reviewing an application to annul a marriage. The reforms imposed by Francis are really about time and money, reducing how long it takes and how much it costs to secure an annulment; the legal basis on which one may be granted remains unchanged, Church teaching being not that the marriage in question failed, but that the sacramental component was always missing. Still, a wind of change is blowing through the Vatican and Mitis iudex dominus Iesus, like other recent reforms, did make clear these were matters for the local bishop, the man closest to his flock.

Putative (pronounced pyoo-tuh-tiv)

Commonly believed or deemed

to be the case; reputed; accepted by supposition rather than as a result of

proof.

1432: From the late Middle

English, from the Middle French putatif,

from the Late Latin putātīvus

(reputed) the construct being putāt(us), past participle of putāre (to think, consider, reckon

(originally “to clean, prune”)) + -īvus

(-ive). The ultimate root was the primitive

Indo-European pau- (to cut, strike, stamp),

the most familiar Latin variants being putātus

(thought) and putō (I think, I

consider, I reckon). The -īvus

suffix was from the primitive Indo-European -ihwós, an extended form of –wós;

it was cognate with the Ancient Greek -εῖος (-eîos)

(from which Latin picked up also -ēus)

and was added to the perfect passive participial stem of verbs, forming a

deverbal adjective meaning “doing” or “related to doing”. Putative is an adjective, putatively an

adverb.

Early use of the word was

almost exclusively in Church Latin as putative

marriage, one which, though legally invalid due to an impediment, was

contracted in good faith by at least one party.

Putative is almost always used in front of a noun, the modified noun

being that which is assumed or supposed to be. The putative cause of a disease

is whatever is generally thought to be the cause, even if unproven. As a point of usage, it’s not correct to say

"the cause was putative."

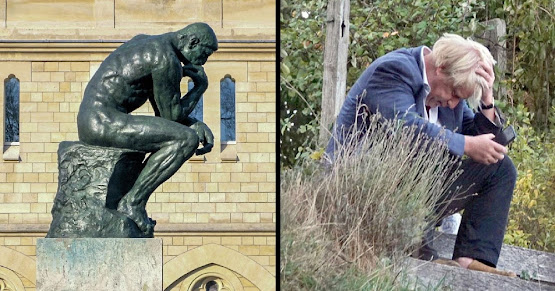

UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s marriage to Roman Catholic Carrie Symonds, mother of the two youngest of his seven children, was celebrated in London's Westminster Cathedral on 29 June 2021, the edifice

briefly closed for the occasion. Unannounced,

as Mr Johnson’s third putative marriage, it attracted particular interest

because it was a Roman Catholic ceremony.

Although probably most of the British public years ago lost any interest

in theology, still widely known is the church’s doctrinal insistence that

marriage is a permanent, lifelong union between a man and a woman, those who

divorce unable to enter a second marriage recognized by the Church.

The prime-minister’s union is however within

church rules. A baptized Catholic, what

he described as his school-boy conversion to Anglicanism was not something

recognized by canon law, Mr Johnson joining the Church of England by a process

the Vatican would view as not much more than him deciding one day he was

Anglican. Not good enough. For any soul to depart the faith, what canon

law requires is a “defection from the Catholic Church by a formal act”, a specifically

defined legal process, undertaken in dialogue with the Church hierarchy and

nothing like that was ever done. Conversion

cannot be effected simply by conduct or press-release and, although what was

done might have made Mr Johnson an Anglican in the eyes of Lambeth, to the Holy

See he was and remained one of them.

Marriage has a long history, the idea of a lifelong

partnership between one man and one woman drawn from of natural law and

something recognized and acknowledged by the Church by virtue of the conduct

and acquiescence of the parties even before the medieval church regularized the

practice in the Code of Canon Law. The code

contains also ecclesiastical laws governing how and when Catholics can enter

marriage, among which is the requirements to conform with “canonical form” including

the ceremony being performed in the parish church of the parties, the permission

of their bishop to marry outside of the Church and the need to seek special

dispensation, sometimes from Rome, to marry non-Christians.

The construction of the framework really began at

the fourth Lateran Council (1215) which banned informal or secret marriages, beginning

the codification of the forms and processes of formal marriage with rules

ensuring marriages would be widely known within the community so (1) any

impediment might be raised prior to or before the conclusion of the ceremony

and (2), once done, neither party could deny the union. This really was social engineering,

addressing the not uncommon event of a man inducing consent from a woman or

girl with assurance he regarded them as betrothed, only later, usually when he

learned she was with child, to renounce the “marriage”. All of this had a good scriptural basis, the

notion of “what therefore God hath joined

together, let not man put asunder” appearing both in Mark 10:9 and Matthew

19:6. Further to strengthen the

framework, after the Council of Trent (Concilium

Tridentinum, 1545-1563, nineteenth ecumenical council of the Catholic

Church, Trent (Trento), Italy), the

marriage sacrament came under jurisdiction of the Church, ceremonies performed

and records maintained by priests.

Unless a marriage conformed to canonical form, it couldn’t be a valid

marriage and, in the eyes of canon lawyers, never happened. That was the legal abstraction. On the ground, parish priests and presumptive

fathers-in-law, knowing what had happened, dealt with miscreant

“husbands”.

Thus the prime minister is a baptized Catholic

subject to the demands of canonical form and one whose previous marriages

lacked canonical form. Any Church

tribunal would be compelled to hold the two unions invalid; they didn’t exist

so he could marry Ms Symonds in a Catholic ceremony in a Catholic Church as his first valid marriage. Helpfully, nor are

sins of the father visited upon the children, the law recognizing the children

born of putative marriages later declared null or invalid to be as legitimate

as those born of valid marriages. The

origin of this lies in the Medieval habit of kings seeking (and gaining,

sometimes on grounds more tenuous than those applying to Mr Johnson) an annulment. Then it was the delicate business of handling

the sunder without messing with long-settled issues of succession.

There are other quirks in Canon law. While the Church does hold only a marriage

between two baptized Christians can be a sacrament, it also recognizes that any

marriage which conforms to its essential properties is valid, regardless of

whether it involves those of other faiths or indeed atheists. The exception is Catholics, on whom is

imposed the more onerous demands of canonical form.