Homage (pronounced hom-ij,

om-ij or oh-mahzh)

(1) Respect or reverence paid or rendered.

(2) In feudal era custom & law, the formal public

acknowledgment by which a feudal tenant or vassal declared himself to be the

man or vassal of his lord, owing him fealty and service; something done in

acknowledgment of vassalage (archaic).

(3) The relation thus established of a vassal to his lord

(archaic).

(4) Something done or given in acknowledgment or

consideration of the worth of another.

(5) To render homage to (archaic except in artistic or

historic use).

(6) An artistic work imitating another in a flattering

style.

(7) A (sometimes controversial) way of describing an

imitation, clone or replica of something.

(8) A demonstration of respect, such as towards an

individual after their retirement or death (often in the form of (an obviously retrospective)

exhibition).

1250–1300: From the Middle English hommage, omage & umage

(the existence of “homage” is contested), from the Old French homage & hommage, from the Medieval Latin homināticum (homage, the service of a vassal or 'man'), the

construct being (h)ome (man), from the from Latin hominem, accusative of homō (a man (and in Medieval Latin “a

vassal”)) + -āticum (the noun-forming

suffix) (-age). The

suffix -age was from the Middle English -age,

from the Old French -age, from the

Latin -āticum. Cognates include the French -age, the Italian -aggio, the Portuguese -agem,

the Spanish -aje & Romanian -aj.

It was used to form nouns (1) with the sense of collection or

appurtenance, (2) indicating a process, action, or a result, (3) of a state or

relationship, (4) indicating a place, (5) indicating a charge, toll, or fee,

(6) indicating a rate & (7) of a unit of measure. The verb homage was derived

from the noun in the late sixteenth century (the agent noun homager noted from the turn of the

fifteenth). In Scots

the spelling was homage and in Irish, ómós and

the old synonym manred has been

obsolete since the fourteenth century. The

predominately US pronunciation with a silent

h happened because of a conflation with the nearly synonymous doublet hommage, pronounced thus. Homage is a noun & verb, homager is a noun, homaged & homaging are verbs and homageable is an adjective; the noun plural is homages. Despite the esistance of homager, the noun homagee seems never to have been acknowledged as a standard form.

By convention, the modern use of the form is usually as “pay

homage to” but because of the variations in pronunciations (the h silent and

not), homage is sometimes preceded by the article “a” and sometimes by “an” and

under various influences in popular culture, the French pronunciation has in

some circles become fashionable. The

term “lip homage” is much the same as “lip service”: something expressed with “mere

words”. In Middle English, the meanings

variously were (1) an oath of loyalty to a liege performed by their vassal; a

pledge of allegiance, (2) money given to a liege by a vassal or the privilege

of collecting such money, (3) a demonstration of respect or honor towards an

individual (including prayer), (4) the totality of a feudal lord's subjects

when collected and (5) membership of an organized religion or belief system. In feudal times, an homage was said to be an “act of

fealty”. The Middle English noun fealty dates from the twelfth century

and was from feaute, from the Old

French feauté, from fealte (loyalty, fidelity; homage sworn

by a vassal to his overlord; faithfulness), from the Latin fidelitatem (nominative fidelitas)

(faithfulness, fidelity), from fidelis

(loyal, faithful), from the primitive Indo-European root bheidh- (to trust, confide, persuade). In feudal law, to attorn was to “transfer homage or allegiance to another lord”. The verb attorn

(to turn over to another) was from the Middle English attournen, from the Old French atorner

(to turn, turn to, assign, attribute, dispose; designate), the construct being a- (to) + tourner (to turn), from the Latin tornare (to turn on a lathe) from tornus (lathe), from the Greek tornos

(lathe, tool for drawing circles), from the primitive Indo-European root tere- (to rub, turn). Attornment was a part English real property

law but was not directly comparable with the operation of those laws which in matters

of slavery assigned property rights over human beings which technically were no

different than those over a horse. Attornment

recognized there was in the feudal system some degree of reciprocity in rights & obligations and it was held to be unreasonable a tenant

should become subject to a new lord without their own approval. At law, what evolved was the doctrine of

attornment which held alienation could not be imposed without the consent of

the tenant. Given the nature of feudal

relations it was an imperfect protection but a considerable advance and attornment

was also extended to all cases of lessees for life or for years. The arrangement regarding the historic feudal

relationships lasted until the early eighteenth century but attornment persists

in modern property law as a mechanism which acts to preserve the essential

elements of commercial tenancies in the event of the leased property changing

hands. It provides for what would now be

called “transparency” in transactions and ensures all relevant information is

disclosed, thereby ensuring the integrity of the due diligence process.

The historical concepts of homage and tribute are

sometimes confused. Homage was a formal ritual

performed by a vassal to pledge loyalty and submission to a lord or monarch. There were variations but the classic model

was one in which the vassal would kneel before the lord, place his hands

between the lord's hands, and swear an oath of loyalty and service. That was not merely symbolic for it signified

the vassal's acknowledgment of the lord's authority and their willingness to

serve and protect the lord in exchange for a right to live on (and from) the land.

The relationship was that creature of

feudalism; something both personal and contractual. Tributes were actual payments made by one

ruler or state to another as a sign of submission, acknowledgment of

superiority, or in exchange for protection or peace. Tribute could be paid in gold, other mediums

of exchange or in the form of goods or

services. Tribute was something imposed

on a subordinate entity by a dominant power, either as a consequence of defeat

in war or as a way of avoiding being attacked (ie a kind of protection racket). The meaning of homage in feudal property law was

quite specific but synonyms (depending on context) now include deference,

tribute, allegiance, reverence, loyalty, obeisance, duty, adoration, fealty,

faithfulness, service, fidelity, worship, adulation, honor, esteem, praise,

genuflection, respect, awe, fidelity, loyalty & devotion. However, those using homage for anything

essentially imitative might find out other synonyms include fake (and more generously faux, tribute, reproduction, pastiche, clone or replica).

One

implication of the acceptance of both pronunciations (the “H” silent and not)

is that both “a homage” and “an homage” are acceptable in written form although

in oral use the later must use the silent “H”.

In US use “an homage” is common with no suggestion of deliberately

“formal” use or artistic association although elsewhere in the English-speaking

world that does seem the case, movie critics everywhere usually careful to

write “an homage” though the style guides seem all to be permissive and caution

only that use should be consistent. There

are in English other words where the choice between “a” & “an” is dictated

by pronunciation and

frequently they’re those where the status of the initial “h” is contested. Although there are still prescriptive pedants,

informally at least there seems to be a general acceptance “H-optional” words do

exists and use is a thing of dialect, register or even personal preference. They wiser style guides also suggest avoiding

the “H war” which is the battle over whether the letter “H” should be

pronounced aitch or haitch, the former long classed a “U

word” as part of “correct” RP (received pronunciation) while the latter was

thought “a bit common”. Historically, the evolution wasn’t quite that

linear but in some places (notably Australia where “haichers” were associated

with (1) Irish ancestry and (2) being a product of the Roman Catholic education

system) the class-identifier sometimes assumed a political dimension. The modern principle is to accept however

individuals choose to “H” and treat it as part of the rich diversity of life.

Other “optional

H” words include “herb” (especially in US use), “historic” (which can be tricky

because the structure of some sentences bests suits “a historic” while in

others “an historic” sounds “natural” and that’s a better guide (at least in

oral use) that any “rule”) and “hotel” (although “an hotel” seems used only in

poetry or as a deliberate archaism). The

most common mistake is probably with “heir” (pronounced air, that correct use rather cruelly applied by the Duchess of

Windsor (Wallis Simpson); 1896–1986) who was known to complain her husband (the

former King Edward VIII (1894–1972) “wasn’t “heir conditioned”). The guiding principle remains to use “a”

before words starting with a consonant sound, and “an” before those starting

with a vowel sound, a “rule” applied regardless of spelling although in scientific,

literary and poetic use there have been exceptions. Although “a hypothesis” is now the standard

form, “an hypothesis” does appear in older texts and it does better suits some

sentences. In poetry both “an harangue”

and “an harbinger” were used because metrically things flowed better but euphony

in poetry is a special case and in general oral and written use the conventional

forms are better. For historic reasons

some outliers do endure such as “an hymn” or “an harlot”, the latter because it’s

set in the linguistic stone of the King

James Version of the Bible (KJV, 1611) but not even the popular use by contemporary

critics of “an horrible” this and

that when writing of William Shakespeare’s (1564–1616) more torrid scenes has

been enough for that to remain respectable.

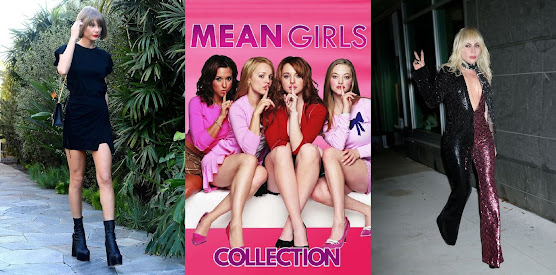

Sample from Ariana Grande’s (b 1993) Thank U, Next (2018).

Singer Ariana Grande’s (b 1993) song Thank U, Next

(2018) was one of the year’s big successes and the video included

well-constructed references to a number of early-century pop culture products

including Legally Blonde (2001) and Mean Girls (2004). Within popular culture, there seems to be a

greater tolerance of works which are in some way an homage, the term “sampling” presumably

chosen to imply what was being done was (1) taking only a small fragment of

someone else’s work and (2) for all purposes within long established doctrine

of “fair use”. Interestingly, instead of

regarding sampling as fair use, US courts initially were quite severe and in

many early cases treated the matter as one of infringement of copyright,

apparently because while a attributed paragraph here and there in a paper of

dozens or hundreds of pages could reasonably seen as “fair use”, a recurring

snatch of even a few seconds in a song only three minutes long was not. Of late, US appeal courts seem to have been

more accommodating of sampling and have taken the view the legal doctrine of de minimis which has been used when

assessing literary or academic works should apply also to sampling but the

mechanics of calculating “fair use” need to be considered in the context of the

product. The Latin phrase de minimis (pertaining to minimal things)

was from the expressions de minimis non

curat praetor (the praetor does not concern himself with trifles) or de minimis non curat lex (the law does

not concern itself with trifles) and was an exclusionary principle by which a

court could refuse to hear or dismiss matters to trivial to bother the justice

system. One Queen of Sweden preferred

the more poetic Latin adage, aquila non

capit muscās (the eagle does not catch flies). As a legal doctrine, it actually predates its

fifteenth century formalization in the textbooks and there are records in civil,

Islamic and ecclesiastical courts of Judges throwing out cases because the

matters involved were of such little matter.

In many jurisdictions, governments now set a certain financial limit for

the matters to be considered, below which they are either excluded or referred

to a tribunal established for such purposes.

One suspects artists, architects, film directors and such

are inclined to call their work an homage (or probably the French hommage (pronounced omm-arge)) as a kind

of pre-emptive strike against accusations of plagiarism or a lack of

originality. Car manufacturers are apt

to do it too, examples in recent decades including the BMW Mini, Volkswagen

Beetle, Dodge Challenger and Chevrolet Camaro, all of which shamelessly

followed the lines of the original versions from generations earlier. The public response to these retro-efforts

was usually positive although if clumsily executed (Jaguar S-Type) derision

soon follows. Sometimes, it’s just a

piece which is homaged. On the Mercedes-Benz

CL (C215 1998-2006), the homage was to the roofline of the W111 & W112

coupés (1961-1971), especially the memorable sweep of the rear glass although

all of that was itself an homage to the 1955 Chryslers. It was a shame the C215 didn’t pick up more

of the W111’s motifs, the retrospective bits easily the best.

1969 Chevrolet Camaro Z/28 (left) and 2023 Chevrolet

Camaro.

The original Chevrolet Camaro (1966-1969)

was a response to the original Ford Mustang (1964) which had given the "pony-car" segment both its name and instant popularity. It was a profitable place to be and while the Camaro's lines were different while adhering to the concept, Chevrolet for 1970 abandoned the look for something almost Italianesque, just as Chrysler picked-up and perfected the cues for the Dodge Challenger & Plymouth, both of which debuted with a splash but didn't last even to the end of 1974 (even Richard Nixon (1913-1994; US president 1969-1974 lasting a little longer), early victims of what would prove a difficult decade. Chevrolet however picked them up again in 2010 but their homage to 1966 was

perhaps a little too heavy-handed, dramatic though the "chop-top" effect was. Still, the result doubtlessly was better that what would have been delivered had the designers come up with anything original and that's not a problem restricted cars. One wishes architects would more often pay homage to mid-century modernism or art deco but the issue seems to be all the awards architects give each other are only for originality, thus the assembly line of the ugly but distinctive.

1970 Dodge Challenger (left) and 2023 Dodge

Challenger (right).

The original

Challenger (and its corporate companions the Plymouth Barracuda & Cuda) was

an homage to the 1966 Camaro and so well executed that Chrysler’s pair are

thought by many to be the best looking pony cars of the muscle car era. In 2008 when the look was reprised, it was thought a most a accomplished effort and better received than would be the

new Camaro two season later. Chevrolet

must have been miffed Dodge was so praised for paying homage to what in 1969

had been borrowed from their 1966 range.

1979 Volkswagen Beetle Cabriolet by Karmann (left) and 2015

Volkswagen Beetle Cabriolet (right).

First produced in 1938, Volkswagen clung to the rear-engine / air-cooled

formula so long it almost threatened the company’s survival and while the

public showed little enthusiasm for a return to the mechanical configuration (the

Porsche 911 crew are a separate species which, if they had their way, would still

not have to bother with cooling fluid), the shape of the Beetle did appeal and

over two generations between 1997-2019, the company sold what was initially

called the “New Beetle”. Despite the

pre-war lines imposing significant packaging inefficiencies, it was popular

enough to endure for almost two decades although the mid-life re-styling never quite succeeded in increasing the appeal to male drivers; to this day the New Beetle remains a quintessential "girl's car".

1966 Austin Mini-Cooper 1275 S (left) and 2001 BMW Mini

(right).

Students of the history of

design insist the BMW Mini was not so much an homage to the British Motor

Corporation’s (BMC) original Mini (1959) but actually to some of the conceptual

sketches which emerged from the design office between 1957-1958 but were judged

too radical for production. That was true but there are enough hints and clues in the production models for

nobody to miss the point.

1965 Jaguar 3.8 S-Type (left) and 1999 Jaguar S-Type.

Released in 1963, the Jaguar S-Type was an

updated Mark 2 with the advantage of more luggage space and markedly improved

ride and handling made possible by the grafting on of the independent

rear-suspension from the E-Type (XKE) and Mark X (later 420G).

The improvements were appreciated but the market never warmed to the

discontinuity between the revised frontal styling and the elongated rear end,

the latter working better when a Mark X look was adopted in front and released as

the 420. Still, although never matching

the appeal of the classic Mark 2 with its competition heritage, it has a period

charm and has a following in the Jaguar collector market. According to contemporary accounts, the homage

launched in 1999 was a good car but it seemed a curious decision to use as a

model a vehicle which has always been criticized for its appearance although

compared with the ungainly retro, the original S-Type (1963-1968) started to

look quite good, the new one the answer to a question something like "What would a Jaguar look like if built by Hyundai?". As an assignment in design school that would have been a good question and the students could have pinned their answers to the wall as a warning to themselves but it wasn't one the factory should ever have posed. Quietly, the new S-Type was dropped

in 2007 after several seasons of indifferent sales.

1956 Chrysler 300B (left), 1970 Mercedes-Benz 280 SE Coupé (centre) and 2005 Mercedes-Benz SL65 (right).

The 1955-1956 Chryslers live in the shadow cast by the big fins which sprouted on the 1957 cars but they possess a restraint and elegance of line which was lost as a collective macropterous madness overtook (most of) the industry. Mercedes-Benz in 1961 paid due homage when the 220 SE Coupé (W111; 1961-1971) was released and returned to the roofline with the C215 (1998-2006). The big coupé was the closest the factory came to styling success in recent years (although the frontal treatment was unfortunate) but one must be sympathetic to the designers because so much is now dictated by aerodynamics. Still, until they too went mad, the BMW design office seemed to handle big coupés better.

In the collector market, there are many low-volume models

which have become highly prized. Some

were produced only in low numbers because of a lack of demand, some because the

manufacturer needed to make only so many for homologation purposes and some

because production was deliberately limited.

Such machines can sell for high prices, sometimes millions so, especially

where such vehicles are based on more mundane models produced in greater

numbers, many are tempted to “make their own”, a task which car range from the

remarkably simple to the actually impossible.

Those creating such things often produce something admirable (and

technically often superior to the original) and despite what some say, there’s

really no objection to the pursuit provided there is disclosure because

otherwise it’s a form of fraud. When

such machines are created, those doing the creating seldom say fake or faux and

variously prefer tribute, clone, recreation, homage or replica and those words in

this context come with their own nuanced meanings, replica for example not meaning exactly

what it does in geometry or database administration.

A 1962 Ferrari 250 GTO in silver (US$70 million) and a fine replica by Tempero of a 1963 model in rosso corsa (racing red) (US$1.2 million). Even the Ferrari cognoscenti concede the craftsmanship in a Termero replica is of a higher standard than the original.

As an extreme example of the homage was inspired by the Ferrari

250 GTO, of which it’s usually accepted 36 were built although there were

actually 41 (2 x (1961) prototypes; 32 x (1962–63) Series I 250 GTO; 3 x

(1962–1963) “330 GTO”; 1 x (1963) 250 GTO with LM Berlinetta-style body & 3

x (1964) Series II 250 GTO). The 36 in

the hands of collectors command extraordinary prices, chassis 4153GT in June

2018 realizing US$70 million in a private sale whereas an immaculately crafted

replica of a 1962 version by Tempero (New Zealand), said to be better built

than any original GTO (although that is damning with faint praise, those who

restore pre-modern Ferraris wryly noting that while the drive-trains were built

with exquisite care, the assembly of the coachwork could be shoddy indeed) was

listed for sale at US$1.3 million. Even

less exalted machinery (though actually more rare still) like the 1971 Plymouth

Hemi Cuda convertible also illustrate the difference for there are now

considerably more clones / replicas / recreations etc than ever there were

originals and the price difference is typically a factor of ten or more. On 13 November 2023, the market will be

tested when a Ferrari 250 GTO (chassis 3765LM) will be auctioned in New York, RM

Sotheby’s, suggesting a price exceeding $US60 million. A number which greatly exceeds or fails by much to

make that mark will be treated a comment on the state of the world economy.