Hedgehog (pronounced hej-hog or heg-hawg)

(1) An Old World, insect-eating mammal of the

genus Erinaceus, especially E. europaeus, and related genera, having a

protective covering of spines on the back (family Erinaceidae, order

Insectivora (insectivores)). They’re

noted for their tactic of rolling into a spiny ball when a threat is perceived.

(2) Any

other insectivore of the family Erinaceidae, such as the moon rat.

(3) In

US use (outside of strict zoological use), any of various other spiny animals,

especially the porcupine

(4) In

military use, a portable obstacle made of crossed logs in the shape of an

hourglass, usually laced with barbed wire or an obstructive device consisting

of steel bars, angle irons, etc, usually embedded in concrete, designed to

damage and impede the boats and tanks of a landing force on a beach (an Ellipsis

of the original Czech hedgehog (an antitank obstacle constructed from three

steel rails)).

(5) In

military (army or other ground forces) use, a defensive pattern using a system

of strong points (usually roughly equally distant from the defended area) where

there exists neither the personnel nor materiel to build a defensive perimeter.

(6) In

(informal) military use, a World War II (1939-1945) era, an anti-submarine, spigot

mortar-type of depth charge, which simultaneously fired a number of explosive charges

into the water to create a pattern of underwater explosions, the multiple

pressure waves creating a force multiplier effect.

(7) In

Australia & New Zealand, a type of chocolate cake (or slice), somewhat

similar to an American brownie.

(8) In

water way engineering & mining, a form of dredging machine.

(9) In

botany, certain flowering plants with parts resembling a member of family

Erinaceidae, notably the Medicago intertexta (Calvary clover, Calvary medick,

hedgehog medick), the pods of which are armed with short spines, the South

African Retzia capensis and the edible fungus Hydnum repandum.

(10) To

array something with spiky projections like the quills of a hedgehog.

(11) In

hair-dressing, a range of spike hair-styles.

(12) An

electrical transformer with open magnetic circuit, the ends of the iron wire

core being turned outward and presenting a bristling appearance.

(13) To

curl up into a defensive ball (often as hedgehogging).

(14) In

catering, a style used for cocktail party food, consisting of a half melon or

potato etc with individual cocktail sticks of cheese and pineapple stuck into

it.

(15) In

differential geometry, a type of plane curve.

(16) In

biochemistry & genetics, as hedgehog signalling pathway, a key regulator of

animal development present in many organisms from flies to humans.

(17) In

biochemistry, as sonic hedgehog, a morphogenic protein that controls cell

division of adult stem cells and has been implicated in the development of some

cancers (sometimes capitalized).

1400–1450:

From the late Middle English heyghoge,

replacing the Old English igl. The construct was hedge + hog, the first

element from the creature’s habit of frequenting hedges, the second a reference

to its pig-like snout. Hedge was from

the Middle English hegge, from the Old

English heċġ, from the Proto-West Germanic

haggju, from the Proto-Germanic hagjō, from the primitive Indo-European kagyóm (enclosure) and was cognate with the Dutch heg and the German Hecke. Hog was from the Middle

English hog, from the Old English hogg, & hocg (hog), which may be from the Old Norse hǫggva (to strike, chop, cut), from the Proto-Germanic

hawwaną (to hew, forge), from the

primitive Indo-European kewh- (to

beat, hew, forge). It was cognate with the

Old High German houwan, the Old Saxon

hauwan, the Old English hēawan (from which English gained “hew”).

Hog originally meant “a castrated male

pig” (thus the sense of “the cut one” which may be compared to hogget (castrated

male sheep)). The alternative etymology

traces a link from a Brythonic language, from the Proto-Celtic sukkos, from the primitive Indo-European

suH- and thus cognate with the Welsh hwch (sow) and the Cornish hogh (“pig”). In the UK, there are a number of synonyms for

mammals with spines, all of which evolved as historic regionalisms and those

which have endured include urchin (listed as archaic but still used in fiction),

furze-pig (West Country), fuzz-pig (West Country), hedgepig (South England),

hedgy-boar (Devon) and prickly-pig (Yorkshire).

Hedge-hog is the alternative form.

Hedgehog is a noun & adjective, hedgehogged & hedgehogging are

verbs and hedgehogless, hedgehoglike & hedgehoggy are adjectives; the noun

plural is hedgehogs.

A

conjecture by German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860), the hedgehog's

dilemma, is a metaphor about the people’s simultaneous long for and the dangers

posed by the quest for human intimacy and social interaction. Schopenhauer illustrated the problem by

describing a group of hedgehogs who in cold weather try to move close together

to share body-heat. However, because of

the danger they pose to each other by virtue of their sharp spines, they are

compelled to maintain a safe distance. As much as they wish to be close, they must

stay distance for reasons beyond their control.

Thus it is with humans who either known instinctively or learn from

bitter experience that it’s not possible to enjoy human intimacy without the risk

of mutual damage and it is this realization which induces caution with others

and stunted relationships. The most

extreme manifestation is self-imposed isolation.

Of

course most in modern societies interact with many others and Schopenhauer wasn’t

suggesting total social avoidance was in any way prevalent but that most

relationships tended to be perfunctory, proper and distant, mediated by “politeness

and good manners” part of which is literally “keeping one’s distance”; what is

now called one’s “personal space”. Even

among German philosophers with their (not always deserved) reputation for going

mad it was a particularly Germanic view which recalls the musing of Frederick

II (Frederick the Great, 1712–1786, Prussian king 1740-1786) that “The more I know of the nature of man, the

more I value the company of dogs”.

It appealed too to other Teutons.

From Vienna, Sigmund Freud (1856-1939) quoted Schopenhauer’s metaphor in

Massenpsychologie und Ich-Analyse (Group

Psychology and the Analysis of the Ego (1921)) and heard in the tale the echoes

of what so many of his patients had said while reclined on his office sofa. He’d certainly have recognized as his own

work the concept of “basic repression” explored by Berlin-born philosopher

Herbert Marcuse (1898–1979) in explaining the mechanisms by which people

maintained the “politeness and good manners” Schopenhauer suggested were

necessary. Marcuse’s contribution was

the idea of “surplus repression”, those restrictions imposed on human behaviour “necessitated by social domination”, a consequence of the social organization

of scarcity and resources in a way not “in accordance with individual needs”. Some Germans however found some additional

repression suited their character. Albrecht

Haushofer (1903–1945), an enigmatic fellow-traveller of the Nazis and for a

long time close to the definitely repressed Rudolf Hess (1894–1987; Nazi deputy

führer 1933-1941) wrote during the early days of the regime that “…I am fundamentally not suited for this new

German world… He, whose faith in human society approximately agrees with

Schopenhauer’s fine parable of the hedgehogs – is unsuitable for the rulers of

today.” That notwithstanding, his faith in the Nazis appeared to overcome his doubts because he remained, off and on, in their service until 1945 when, during the last days of the war, he was murdered by the regime.

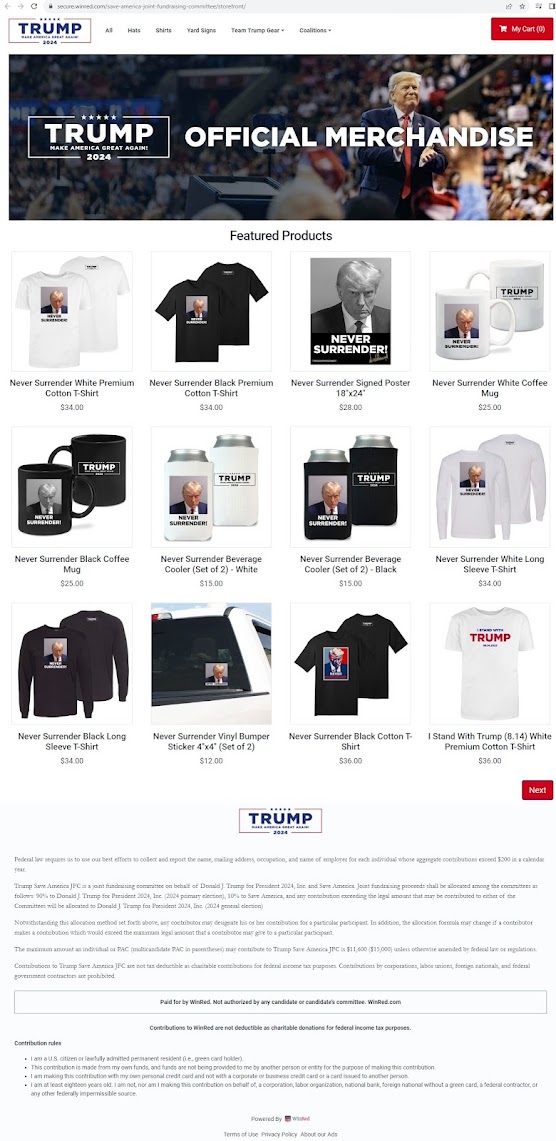

Variations of the hedgehog look.

There

little to suggest that German habitué of the British Library’s reading rooms, Karl

Marx (1818-1883), much dwelled upon hedgehogs, zoological or metaphorical but

those who wrote of his work did. In The Hedgehog and the Fox (a fine essay

on Tolstoy published in 1953), Sir Isaiah Berlin (1909-1997) quoted a fragment

from the Greek lyric poet Archilochus (circa 680–circa 645 BC): “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog

knows one big thing”. Hedgehogs,

wrote Berlin, were those “…who relate

everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or

articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel—a single,

universal, organizing principle in terms of which alone all that they are and

say has significance” while foxes “…pursue

many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only

in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to

no moral or esthetic principle”. The

hedgehog then is like the scientist convinced the one theory, if worked at for

long enough, will yield that elusive unified field theory and is “…the monist who relates everything to a

central, coherent, all-embracing system” while the fox is the pluralist

intrigued by “the infinite variety of

things often unrelated and even contradictory to each other”. Berlin approved of foxes because they seemed

to “look and compare” before finding some

“degree of truth” which might offer “a point of view” and thus “a starting-point for genuine investigation”. He labelled Plato, Lucretius, Pascal, Hegel,

Dostoevsky, Nietzsche and Proust as hedgehogs (to one degree or another) while Herodotus,

Aristotle, Montaigne, Erasmus, Moliere, Goethe, Pushkin, Balzac, Joyce were

foxes. To Berlin, Marx was a hedgehog

because he pursued a universal explanatory principle in his advocacy of a

materialist conception of history.

Berlin’s thesis was attracted much interest including from Marxists and

neo-Marxists and their priceless addition to English was the “quasi-hedgehog” to describe their view

being there were more shades to Marx than those of a hedgehog but lest than

those of the fox. Presumably the term

quasi-hedgehog was coined because a hybrid of a fox and hedgehog was either unthinkable,

unimaginable or indescribable.