Hypergolic (pronounced hahy-per-gaw-lik or hahy-per-gol-ik)

(1) In chemistry, a process in which one substance ignites spontaneously upon contact with a complementary substance (oxidizer). Word applies especially to bipropellant (made of two components) rocket-fuel.

(2) Of or relating to hypergols.

1945: A backronym derived from the German hypergol, a construct of scientific use: hyp(er) + erg + ol + -ic. Hyper is from the Ancient Greek ὑπέρ (hupér) (over; extreme); erg from the Ancient Greek ἔργον (érgon) (work), ol both from from the chemical suffix ol from alcohol & the Latin oleum (oil) and ic, the adjectival suffix, variations of which are widely used in European languages (the Middle English ik, the Old French ique, the Latin icus, all thought derived from the primitive Indo-European ikos; oldest known forms are the Ancient Greek ικός (ikós), the Sanskrit श (śa) & क (ka) and the Old Church Slavonic -ъкъ (-ŭkŭ)). The hypergole terminology was coined by Dr Wolfgang Nöggerath (1908-1973) of the Technical University of Brunswick, Germany. Few are as linguistically imaginative as scientists who plunder languages at will to produce the best or most memorable words to describe their creations. Hypergolic is a noun & adjective; the noun plural is hypergolics.

The

Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet

During

the 1930s, almost all research into rocket propellants was undertaken in

Germany, the military being interested in missiles with which to deliver

warheads against long-range targets and, even then, some scientists were

imagining space flight, usually with a manned visit to the moon in mind. The experimental fuels were classed as:

Monergols: Single

ingredient fuels.

Hypergols: Fuel which

ignites upon constituents being combined.

Non-hypergols: Multi-constituent

fuel requiring external ignition.

Lithergols: Solid /

liquid hybrids.

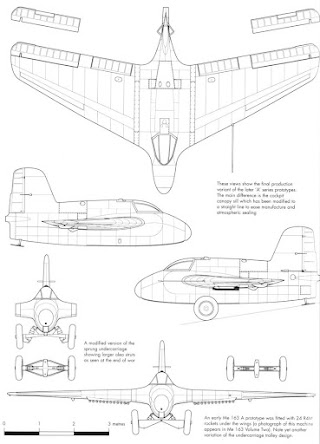

It was only military necessity that forced the Luftwaffe (the German air force) to commit to combat the only rocket-powered fighter ever deployed. The Messerschmitt Me-163 Komet was powered by a rocket which burned a methanol hydrazine mix with hydrogen- peroxide as an oxidizer. It offered a uniquely fast rate of climb and a speed in combat more than 100 mph (160 km/h) faster than allied fighters but was hard to handle and the fuel was both highly volatile and prone to spontaneous combustion in flight or on the ground. In air engagements, the speed which was so advantageous in reaching a target made it difficult for a pilot to maintain contact, the long bursts of fire need usually to bring down the big bombers rarely sustained. Most authorities estimate some 370 Me-163s were built but only 60-80 achieved operational status and they shot down only nine allied aircraft. The Komet effectiveness was limited by its high fuel consumption which limited flight duration (the time available in the combat zone less than eight minutes) but the Luftwaffe's records confirm that on some days, such was the accident rate, not even half the little craft even reached operational height. Not only was it a difficult machine to handle but, late in the war, resources were so strained that training was limited and few of the Komet's pilots had more than a few hours experience in the craft before deployment. To make matters worse, although in powered flight its speed make it close to invulnerable to attack, once the fuel was burned, to return to base it had to glide down to the runway and of those lost to allied fighters, most were shot-down during landing or on the ground.

It was another example of the impressive wartime technology developed by German scientists and engineers which failed to realise the possibilities offered. Had the resources expended on the Komet instead been devoted to improving the Wasserfall (waterfall) rocket, Allied air losses might have been significantly greater. The Wasserfall was a surface-to-air missile explicitly designed to counter high altitude bombers and used a two-stage system: (1) a solid-fueled booster rocket for launch after which (2) a liquid-fueled rocket would propel the missile to its target. A glimpse of the future, it was guided by a radar system that tracked the target & transmitted guidance commands and was designed to be integrated with other ground-based anti-aircraft defenses such as flak batteries. Ultimately unsuccessful because the time and resources needed for development were never available, like the V1 (an early cruise missile) and V2 (the first operational ballistic missile), the hardware, personnel and data which fell into Allied hands at the end of the war essentially saved decades of peace-time work in projects including surface to air & air to air missiles, the space programme (notably the moon landing) and the the development of the big ICBMs (intercontinental ballistic missiles). Historically, the Komet remains a one-off, no rocket-powered fighters since manufactured. In action only between 1944-1945, tactically, it was a failure, losses far exceeding kills, but it influenced the next generation of military airframes being developed for supersonic flight.