Simulacrum (pronounced sim-yuh-ley-kruhm)

(1) A slight, unreal, or superficial likeness or

semblance; a physical image or representation of a deity, person, or thing.

(2) An effigy, image, or representation; a thing which

has the appearance or form of another thing, but not its true qualities; a

thing which simulates another thing; an imitation, a semblance; a thing which

has a similarity to the appearance or form of another thing, but not its true

qualities

(3) Used loosely, any representational image of something (a nod to

the Latin source).

1590–1600: A learned borrowing of the Latin simulācrum (likeness, image) and a

dissimilation of simulaclom, the

construct being simulā(re) (to pretend, to imitate), + -crum (the instrumental suffix which was a

variant of -culum, from the primitive

Indo-European –tlom (a suffix forming

instrument nouns). The Latin simulāre was the present active

infinitive of simulō (to represent,

simulate) from similis (similar to;

alike), ultimately from the primitive Indo-European sem- (one; together). In

English, the idea was always of “something having the mere appearance of

another”, hence the conveyed notion of a “a specious imitation”, the

predominant sense early in the nineteenth century while later it would be

applied to works or art (most notably in portraiture) judged, “blatant flattery”. In English, simulacrum replaced the late

fourteenth century semulacre which

had come from the Old French simulacre. As well as the English simulacrum, the descendents from the

Latin simulācrum include the French simulacre,

the Spanish simulacro

and the Polish symulakrum. Simulacrum is a noun and simulacral is an adjective; the

noun plural is simulacrums or simulacra (a learned borrowing from Latin

simulācra). Although neither is listed,

by lexicographers, in the world of art criticism, simulacrally would be a

tempting adverb and simulacrumism an obvious noun. The comparative is more simulacral, the

suplerative most simulacral.

Simulacrum had an untroubled etymology didn’t cause a

problem until French post-structuralists found a way to add layers of

complication. The sociologist &

philosopher Jean Baudrillard (1929-2007) wrote a typically dense paper (The Precession of Simulacra (1981))

explaining simulacra were “…something that replaces reality with its representation… Simulation

is no longer that of a territory, a referential being, or a substance. It is

the generation by models of a real without origin or reality: a hyperreal....

It is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It

is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real.”

and his examples ranged from Disneyland to the Watergate scandal. Although dense, this one did stop short of the impenetrability he sometimes achieved and one can see his point but it seems only to state

the obvious; wicked types like Karl Marx (1818-1883) and Joseph Goebbels

(1897-1975; Nazi propaganda minister 1933-1945) said it in fewer words. To be fair, Baudrillard’s point was more

about the consequences of simulacra than the process of their creation and the

social, political and economic implication of states or (more to the point)

corporations attaining the means to “replace” reality with a constructed

representation were profound. The idea

has become more relevant (and certainly more discussed) in the post-fake news

world in which clear distinctions between that which is real and its imitations

have become blurred and there’s an understanding that through many channels of

distribution, increasingly, audiences are coming to assume "nothing is real". In the age of AI (artificial intelligence) generated images, voice and video content which is indistinguishable from "the real" it would seem unwise to assume anything "necessarily is real".

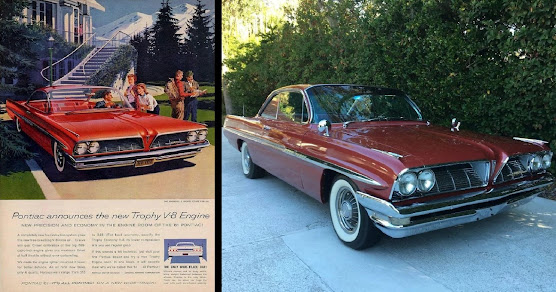

Mannerist but not quite surrealist: Advertising for the 1961 Pontiac Bonneville Sports Coupe (left) with images by Art Fitzpatrick (1919–2015) & Van Kaufman (1918-1995) and a (real) 1961 Pontiac Bonneville Sports Coupe (right) fitted with Pontiac's much admired 8-lug wheels, their exposed centres actually the brake drum to which the rim (in the true sense of the word) directly was bolted.

The work of Fitzpatrick & Kaufman is the best remembered of the 1960s advertising by the US auto industry and their finest creations were those for General Motors’ (GM) Pontiac Motor Division (PMD). The pair rendered memorable images but certainly took some artistic licence and created what were even then admired as simulacrums rather than taken too literally. While PMD’s “Year of the Wide-Track” (introduced in 1959) is remembered as a slogan (the original advertising copy read “Wide Track Wheels” but was soon clipped to “Wide Track” because it was snappier), it wasn’t just advertising shtick, the decision taken to increase the track of Pontiacs by 5 inches (127 mm) because the 1958 frames were carried-over for the much wider 1959 bodies, rushed into production because the sleek new Chryslers had rendered the old look frumpy and suddenly old-fashioned. That spliced0in five inches certainly enhanced the look but the engineering was sound, the wider stance did genuinely improve handling. Just to make sure people got the message about the “wide” in the “Wide Track” theme, the advertising artwork deliberately exaggerated the width of the cars they depicted and while it was the era of “longer, lower, wider” (and PMD certainly did their bit in that), things never got quite that wide. Had they been, the experience of driving would have felt something like steering an aircraft carrier's flight deck.

1908 Cadillac Model S: The standard 56 inch (1422 mm) track (left) and the 61 inch (1549 mm) "wide track" (right), the more "sure-footed" stance designed for rutted rural roads. The early automobiles used a narrower track than the traditional horse-drawn carriages and while this tended not to cause motorists difficulties in urban conditions (indeed, the narrower profile was often a great advantage when negotiating around the built environment), in rural areas where road maintenance between distant settlements was usually infrequent and sometimes non-existent, unless able (especially in winter) to play the wheels of one's vehicle in the well-worn tracks of a thousand or more before, progress often simply had to stop. Thus Cadillac's Model S, the additional width spliced into the structure designed exactly to match the ruts in the roads of the rural Southwest, cut by generations of horse-drawn wagons.

Pontiac made much of the “Year of the Wide Track” and it worked so well “wide track” would be an advertising hook for much of the 1960s although the idea wasn’t new, Cadillac in 1908 offering a wide track option for their Model S. While the four cylinder Cadillacs were coming to be offered with increasingly large and elaborate coachwork, to increase the appeal of the single cylinder, 98 cubic inch (1.6 litre) Model S for rural buyers, there was the option of a 61 inch (1549 mm) track, 5 inches (127 mm) wider than standard. Though a thoughtful gesture, times were changing and the 1908 Model S would prove the last single cylinder Cadillac, the corporation the next season standardizing the line around the Model Thirty which upon release would use the 226 cubic inch (3.7 litre) four-cylinder engine although in a harbinger of the 1950s and 1960s, it would be enlarged to 255 cubic inches (4.2 litre) for 1910, 286 cubic inches (4.7 litres) for 1911-1912 and finally 366 cubic inches (6.0 litres) for 1914. For 1915, there was another glimpse of Cadillac’s path in the twentieth century with the introduction of the Model 51, fitted with the company’s first V8 with a displacement of 314 cubic inches (5.1 litres). As the photographs suggest, nor was there anything new in the luxurious tufted leather upholstery Detroit in the 1970s came to adore, the style of seating used in the early (“brass era”), up-market automobiles taken straight from gentlemen’s clubs.

Fitzpatrick & Kaufman’s graphic art for the 1967 Pontiac Catalina Convertible advertising campaign. One irony in the pair being contracted by PMD is that for most of the 1960s, Pontiacs were distinguished by some of the industry’s more imaginative and dramatic styling ventures and needed the artists' simulacral tricks less than some other manufacturers (and the Chryslers of the era come to mind, the solid basic engineering below cloaked sometimes in truly bizarre or just dull bodywork).

This advertisement from 1961 hints also at something often not understood about what was later acknowledged as the golden era for both the US auto industry and their advertising agencies. Although the big V8 cars of the post-war years are now remembered mostly for the collectable, high-powered, high value survivors with large displacement and induction systems using sometimes two four-barrel or three two-barrel carburetors, such things were a tiny fraction of total production and most V8 engines were tuned for a compromise between power (actually, more to the point for most: torque) and economy, a modest single two barrel sitting atop most and after the brief but sharp recession of 1958, even the Lincoln Continental, aimed at the upper income demographic, was reconfigured thus in a bid to reduce the prodigious thirst of the 430 cubic inch (7.0 litre) MEL (Mercury-Edsel-Lincoln) V8. Happily for country and oil industry, the good times returned and by 1963 the big Lincolns were again guzzling gas four barrels at a time (the MEL in 1966 even enlarged to a 462 (7.6)) although there was the courtesy of the engineering trick of off-centering slightly the carburetor’s location so the primary two throats (the other two activated only under heavy throttle load) sat directly in the centre for optimal smoothness of operation. Despite today’s historical focus on the displacement, horsepower and burning rubber of the era, there was then much advertising copy about (claimed) fuel economy, though while then as now, YMMV (your mileage may vary), the advertising standards of the day didn’t demand such a disclaimer.

Portrait of Oliver Cromwell (1650), oil on canvas by Samuel Cooper (1609-1672).

Even if it’s something ephemeral, politicians are often

sensitive about representations of their image but concerns are heightened when

it’s a portrait which, often somewhere hung on public view, will long outlive

them. Although in the modern age the

proliferation and accessibility of the of the photographic record has meant

portraits no longer enjoy an exclusivity in the depiction of history, there’s

still something about a portrait which conveys, however misleadingly, a certain

authority. That’s not to suggest the

classic representational portraits have always been wholly authentic, a good

many of those of the good and great acknowledged to have been painted by

“sympathetic” artists known for their subtleties in rendering their subjects

variously more slender, youthful or hirsute as the raw material required. Probably few were like Oliver Cromwell

(1599–1658; Lord Protector of the Commonwealth 1653-1658) who told Samuel

Cooper to paint him “warts and all”.

The artist obliged.

Randolph Churchill (1932), oil on canvas by Philip de László (left) and Randolph Churchill’s official campaign photograph (1935, right).

There have been artists for whom a certain fork of the simulacrum

has provided a long a lucrative career.

Philip Alexius László de Lombos (1869–1937 and known professionally

as Philip de László) was a UK-based Hungarian painter who was renowned for his sympathetic

portraiture of royalty, the aristocracy and anyone else able to afford his fee

(which for a time-consuming large, full-length works could be as much as 3000

guineas). His reputation as a painter suffered

after his death because he was dismissed by some as a “shameless flatterer” but in more

recent years he’s been re-evaluated and there’s now much admiration for his

eye and technical prowess, indeed, some have noted he deserves to be

regarded more highly than many of those who sat for him. His portrait of Randolph Churchill

(1911-1968) (1932, left) has, rather waspishly, been described by some authors

as something of an idealized simulacrum and the reaction of the journalist Alan

Brien (1925-2008) was typical. He met

Churchill only in when his dissolute habits had inflicted their ravages and

remarked that the contrast was startling, “…as if Dorian Gray had changed places with his picture for

one day of the year.”

Although infamously obnoxious, on this occasion

Churchill responded with good humor, replying “Yes, it is hard to believe that was me,

isn’t it? I was a joli garçon (pretty boy) in those days.” That may have been true for as his official

photograph for the 1935 Wavertree by-election (where he stood as an “Independent

Conservative” on a platform of rearmament and opposition to Indian Home Rule)

suggests, the artist may have been true to his subject. Neither portrait now photograph seems to have

helped politically and his loss at Wavertree was one of several he would suffer

in his attempts to be elected to the House of Commons.

Portrait of Gina Rinehart (née Hancock, b 1954) by Western Aranda artist Vincent Namatjira (b 1983), National Gallery of Australia (NGA) (left) and photograph of Gina Rinehart (right).

While some simulacrums can flatter to deceive, others are simply unflattering. That was what Gina Rinehard (described habitually as “Australia’s richest woman”) felt about two (definitely unauthorized) portraits of which are on exhibition at the NGA. Accordingly, she asked they be removed from view and “permanently disposed of”, presumably with the same fiery finality with which bonfires consumed portraits of Theodore Roosevelt (TR, 1858–1919; US president 1901-1909) and Winston Churchill (1875-1965; UK prime-minister 1940-1945 & 1951-1955), both works despised by their subjects. Unfortunately for Ms Reinhart, her attempted to save the nation from having to look at what she clearly considered bad art created only what is in law known as the “Streisand effect”, named after an attempt in 2003 by the singer Barbra Streisand (b 1942) to suppress publication of a photograph showing her cliff-top residence in Malibu, taken originally to document erosion of the California coast. All that did was generate a sudden interest in the previously obscure photograph and ensure it went viral, overnight reaching an audience of millions as it spread around the web. Ms Reinhart’s attempt had a similar consequence: while relatively few had attended Mr Namatjira’s solo Australia in Colour exhibition at the NGA and publicity had been minimal, the interest generated by the story saw the “offending image” printed in newspapers, appear on television news bulletins (they’re still a thing with a big audience) and of course on many websites. The “Streisand effect” is regarded as an example “reverse psychology”, the attempt to conceal something making it seem sought by those who would otherwise not have been interested or bothered to look. People should be careful in what they wish for.

Side by side: Portraits of Barak Obama (2011) and Donald Trump (2018), both oil on canvas by Sarah A Boardman, on permanent display, Gallery of Presidents, Third Floor, Rotunda, State Capitol Building, Denver, Colorado.

In March 2025 it was reported Donald Trump (b 1946; US president 2017-2021 and since 2025) was not best pleased with a portrait of him hanging in Colorado’s State Capitol; he damned the work as “purposefully distorted” and demanded Governor Jared Polis (b 1975; governor (Democratic) of Colorado since 2019) immediately take it down. In a post on his Truth Social platform, Mr Trump said: “Nobody likes a bad picture or painting of themselves, but the one in Colorado, in the State Capitol, put up by the Governor, along with all the other Presidents, was purposefully distorted to a level that even I, perhaps, have never seen before. The artist also did President Obama and he looks wonderful, but the one on me is truly the worst. She must have lost her talent as she got older. In any event, I would much prefer not having a picture than having this one, but many people from Colorado have called and written to complain. In fact, they are actually angry about it! I am speaking on their behalf to the radical left Governor, Jared Polis, who is extremely weak on crime, in particular with respect to Tren de Aragua, which practically took over Aurora (Don’t worry, we saved it!), to take it down. Jared should be ashamed of himself!”

At the unveiling in 2019 it was well-received by the reverential Republicans assembled and if Fox News had an art critic (the Lord forbid), she would have approved but presumably that would now be withdrawn and denials issued it was ever conferred.

Intriguingly, it was one of Mr Trump’s political fellow-travellers (Kevin Grantham (b 1970; state senator (Republican, Colorado) 2011-2019) who had in 2018 stated a GoFundMe page to raise the funds needed to commission the work, the US$10,000 pledged, it is claimed, within “a few hours”. Ms Boardman’s painting must have received the approval of the Colorado Senate Republicans because it was them who in 2019 hosted what was described as the “non-partisan unveiling event” when first the work was displayed hanging next to one of Mr Trump’s first presidential predecessor (Barack Obama (b 1961; US president 2009-2017), another of Ms Boardman’s commissions. Whether or not it’s of relevance in the matter of now controversial portrait may be a matter for professional critics to ponder but on her website the artist notes she has “…always been passionate about painting portraits, being particularly intrigued by the depth and character found deeper in her subjects… believing the ultimate challenge is to capture the personality, character and soul of an individual in a two-dimensional format...” Her preferred models “…are carefully chosen for their enigmatic personality and uniqueness...” and she admits some of her favorite subjects those “whose faces show the tracks of real life.”

Variations on a theme of simulacra: Four AI (artificial intelligence) generated images of Lindsay Lohan by Stable Diffusion. The car depicted (centre right) is a Mercedes-Benz SL (R107, 1971-1989), identifiable as a post-1972 North American model because of the disfiguring bumper bar.

So a simulacrum is a likeness of something which is

recognizably of the subject (maybe with the odd hint) and not of necessity “good”

or “bad”; just not exactly realistic. Of

course with techniques of lighting or angles, even an unaltered photograph can similarly

mislead but the word is used usually of art or behavior such as “a simulacrum or pleasure” or “a ghastly

simulacrum of a smile”. In film and biography

of course, the simulacrum is almost

obligatory and the more controversial the subject, the more simulacral things

are likely to be: anyone reading AJP Taylor’s study (1972) of the life of Lord

Beaverbrook (Maxwell Aitken, 1879-1964) would be forgiven for wondering how

anyone could have said a bad word about the old chap. All that means there’s no useful

antonym of simulacrum because one

really isn’t needed (there's replica, duplicate etc but the sense is different) while the synonyms are many, the choice of which should be

dictated by the meaning one wishes to denote and they include: dissimilarity, unlikeness,

archetype, clone, counterfeit, effigy, ersatz, facsimile, forgery, image, impersonation,

impression, imprint, likeness, portrait, representation, similarity, simulation,

emulation, fake, faux & study. Simulacrum

remains a little unusual in that while technically it’s a neutral descriptor,

it’s almost always used with a sense of the negative or positive.