War (pronounced wawr)

(1) A

conflict carried on by force of arms, as between nations or between parties

within a nation; warfare, as by land, sea, or air; in the singular, a specific

conflict (eg Second Punic War).

(2) A

state or period of armed hostility or active military operations.

(3) A

contest carried on by force of arms, as in a series of battles or campaigns.

(4) By

extension, a descriptor for various forms of non-armed conflict (war on

poverty, trade war, war on drugs, war on cancer, war of words etc).

(5) A

type of card game played with a 52 card pack.

(6) A

battle (archaic).

(7) To

conduct a conflict.

(8) In

law, the standard abbreviation for warrant (and in England, the county Warwickshire.

Pre 1150:

The noun was from the Middle English werre,

from the late Old English were, were &

wyrre (large-scale military conflict)

(which displaced the native Old English ġewinn),

from the Old Northern French were

& werre (variant of Old French guerre (difficulty, dispute; hostility;

fight, combat, war)), from the Medieval Latin werra, from the Frankish werru

(confusion; quarrel), from the Old Norse verriworse

and was cognate with the Old High German werra

(confusion, strife, quarrel), the German verwirren

(to confuse), the Old Saxon werran (to

confuse, perplex), the Dutch war (confusion, disarray) and the West Frisian war

(defense, self-defense, struggle (also confusion). Root was the primitive Indo-European wers- (to mix up, confuse, beat, perplex)

and the Cognates are thought to suggest the original sense was "to bring

into a state of confusion”. The verb was

from the Middle English, from the late Old English verb transitive werrien (to make war upon) and was derivative

of the noun. The alternative English

form warre was still in use as late

as the seventeenth century.

Developments

in other European languages including the Old French guerrer and the Old North French werreier. The Spanish,

Portuguese, and Italian guerra also

are from the Germanic; why those speaking Romanic tongues turned to the Germanic

for a word meaning "war" word is speculative but it may have been to

avoid the Latin bellum (from which is derived bellicose) because its form

tended to merge with bello- (beautiful). Interestingly and belying the reputation

later gained, there was no common Germanic word for "war" at the dawn

of historical times. Old English had

many poetic words for "war" (wig,

guð, heaðo, hild, all common in personal names), but the usual one to

translate Latin bellum was gewin (struggle,

strife (and related to “win”).

Lindsay

Lohan making the pages of Foreign Policy

(FP), July 2007. Despite the title, FP’s

content is sometimes discursive and popular culture figures can appear.

Foreign Policy (FP) was in 1970 founded by Harvard’s

Professor Samuel Huntington (1927-2008) and was always intended to be a

clearing house for lively, punchy articles in the field of international

relations yet not constrained by formal, academic traditions, exemplified by a magazine

like Foreign Affairs, published by the

US think-tank the Council on Foreign

Relations. Professor Huntington is

best remembered for his “Clash of

Civilizations” (CoC, 1993) theory which, noting one of threads in world history

of the last 1300-odd years, argued the defining conflict of the future would

between Western civilization and the multi-national Islamic world, the old

order of wars between nation-states rendered obsolete by changes in technology

and geopolitics. The unusual period at

the end of the Cold War (1946-1991) was a time of TLAs (three-letter acronym),

the era remembered also for US political scientist Francis Fukuyama’s coining

of the “End of History” (EoH, 1992) the thesis being that with Western liberal

democracy prevailing over the Soviet communist model, the end-point of humanity’s

search of the ideal political and economic systems had been reached and it was

that Western liberal democracy which would be the universal form, history in

that sense, thus ended. Unfortunately, since

the EoH was declared, wars, if no longer declared, have continued to be waged.

War-time

appeared first in the late fourteenth century; the territorial conflicts

against Native Americans added several forms including warpath (1775), war-whoop

(1761), war-dance (1757), war-song (1757) & war-paint (1826) the last of

which came often to be applied to war-mongering (qv) politicians (as in "putting on their war-paint"), a profession

which does seem to attract blood-thirsty non-combatants. War crimes, although widely discussed for

generations, were first discussed in the sense of being a particular set of

acts which might give rise to specific offences which could be codified in International Law: A Treatise (1906) by

LFL Oppenheim (1858–1919). The war chest

dates from 1901 although even then it’s use was certainly almost always figurative;

in the distant past there presumably had in treasuries been chests of treasure

to pay for armies. War games, long an

essential part of military planning, came to English from the German Kriegspiel, the Prussians most advanced

in such matters because the innovative structure of their general staff system.

In

English, war is most productive as a modifier, adjective etc and examples

include: Types of war: Cold War, holy war, just war, civil war, war of

succession, war of attrition, war on terror etc; Actual wars: World War

I, Punic Wars, First Gulf War, Korean War, Hundred Years' War, Thirty Years'

War, Six-day War etc; Campaigns against various social problems: War on

Poverty, War on Drugs, War on cancer; The culture wars: War on Christmas,

war on free speech; In commerce: Price wars, Cola Wars, turf war; In

crime: turf war (also used in conventional commerce), gang war, Castellammarese

War; In technology: Bus wars, operating system wars, browser wars; Various:

pre-war, post-war, inter-war, man-o'-war, war cabinet, warhead, warhorse, warlord,

war between the sexes, war bond, war reparations, war room.

Film set

for the War Room in Dr Strangelove (1964).

Pre-war and post-war need obviously

to be used in context; “pre-war” which in the inter-war years almost always meant

pre-1914, came after the end of WWII to mean pre-1939 (even in US historiography). “Post-war” tracked a similar path and now

probably means the years immediately after WWII, the era generally thought to

have ended (at the latest) in 1973 when the first oil shock ended the long

boom. Given the propensity over the centuries

for wars between (tribes, cities, kings, states etc) to flare up from time to

time, there have been many inter-war periods but the adjective inter-war didn’t

come into wide use until the 1940s when it was used exclusively to describe the

period (1918-1939) between the world wars.

The phrase “world war”, although tied to the big, multi-theatre

conflicts of the twentieth century, had been used speculatively as early as

1898, then in the context of the US returning the Philippines (then a colonial

possession) to Spain, trigging European war into which she might be drawn. “Word War” (referring to the 1914-1918

conflict which is regarded as being “world-wide” since 1917 when the US entered

as a belligerent) was used almost as soon as the war started but “Great War”

continued to be the preferred form until 1939 when used of “world war” spiked;

World War II came into use even before Russian, US & Japanese involvement

in 1941. For as long as there have been

the war-like there’s presumably been the anti-war faction but the adjectival anti-war

(also antiwar) came into general use only in 1812, an invention of American

English, in reference to opposition to the War of 1812, the use extending by

1821 to describe a position of political pacifism which opposed all war. War-monger (and warmonger) seems first to

have appeared in Edmund Spenser’s (circa 1552-1599) Faerie Queene (1590) although it’s possible it may have prior

currency. The warhead was from 1989, used

by engineers to describe the "explosive part of a torpedo", the use

later transferred during the 1940s to missiles.

The warhorse, attested from the 1650s, was a "powerful horse ridden

into war", one selected for strength and spirit and the figurative sense

of "seasoned veteran" of anything dates from 1837. The (quasi-offensive though vaguely admiring) reference to women perceived as tough was noted in 1921.

Man-o'-war (also as man-of-war) was an old form meaning "fighting man, soldier" while the meaning "armed ship, vessel

equipped for warfare" was from the late fifteenth century and was one of

the primary warships of early-modern navies, the sea creature known as the

Portuguese man-of-war (1707) so called for its sail-like crest. The more common form was “man o' war”. The Cold War may have started as early as

1946 but certainly existed from some time in 1947-1948; it was a form of "non-hostile

belligerency” (although the death–toll in proxy-wars fought for decades on its

margins was considerable); it seems

first to have appeared in print in October 1945 in a piece by George Orwell

(1903—1950). The companion phrase “hot

war” is actually just a synonym for “war” and makes sense only if used in

conjunction with “cold war”. The cold

war was memorably defined by Lord Cherwell (Professor Frederick Lindemann,

1886–1957) as “two sides for years

counting their missiles”.

On June 6, 2025,

Friedrich Merz (b 1955, German chancellor since 2025) visited the White

House. He mentioned the war! Donald Trump (b 1946; US president 2017-2021 and since 2025) would have been pleased by that

because his aides would repeatedly have told him: “Don’t mention the war!”

The

chancellor’s reference was to “D-Day”, the Allied amphibious invasion of France

on 6 June, 1944 and coincidently, the chancellor was born 11 November 1955, 37

years to the day after the signing of the armistice which ended World War I (1914-1918);

the eleventh of November is now marked as “Remembrance Day” in the Commonwealth

and “Veterans Day” in the US. The D-Day

invasion was the Allies biggest single combined operation of World War II

(1939-1945) and remains the largest triphibious invasion in the history of

warfare. The portmanteau adjective triphibious

was a blend of tri-(three) + (am)phibious

and referred to the combined use of air, naval and ground forces. The tri- prefix was from the Latin tri- (three) and the Ancient Greek τρι-

(tri-) (three) while amphibious was

from the Ancient Greek ἀμφίβιος

(amphíbios), the construct being ἀμφί (amphí) (in this context “about, concerning”) + βίος (bíos) (life). Military historians like triphibious but not

all etymologists approve.

A civil war

(battles among fellow citizens or within a community (as opposed to between

tribes, cities, nations etc)) is civil in the sense of "occurring among fellow citizens"

and the term dates from the fourteenth century batayle ciuile (civil battle), the exact phrase “civil war”

attested from late fifteenth century in the Latin bella civicus. In Ancient

Rome, the rather nasty squabbles between the Optimates and the Senate Elites were

known as bellum civile but should in

English be understood as “governance war” because what was being described was

a factional power-struggle for the control of Rome rather than a “civil war” as

it is now understood. The instances of

what would now be called civil war pre-date antiquity but the early references

typically were in reference to ancient Rome where the conflicts were, if not

more frequent, certainly better documented.

A word for the type of conflict in the Old English was ingewinn and in Ancient Greek it had

been polemos epidemios.

The struggle in England

between the parliament and Charles I (1600-1649) has always and correctly been

known as the English Civil War (1642-1651) whereas there are scholars who

insist the US Civil War (1861-1865) should rightly be called the “War of

Secession”, the “war between the States" or the “Federal-Confederate

War”. None of the alternatives ever

managed great traction and “US Civil War” has long been the accepted form

although, when memories were still raw, if there was ever a disagreement, the

parties seem inevitability to have settled on “the War”. The phrases pre-war and post-war are never

applied the US Civil War, the equivalents being the Latin forms ante-bellum (literally “before the war”)

and post-bellum (literally “after the

war”). The word “civil” of course is

used in other ways and there has rarely be much that in another sense is “civil”

about civil wars so when fought in what is thought to be in accordance with the

“rules of war”, phrases like “chivalrous war” or “clean war” tend to be used

although however fought, wars are a ghastly business are there are simply

degrees of awfulness.

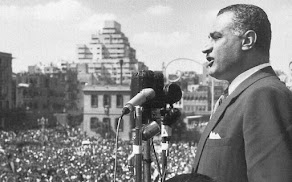

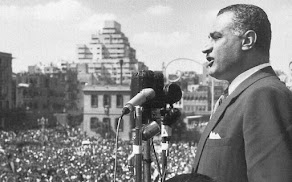

Colonel

Nasser, president of Egypt, Republic Square, Cairo, 22 February 1958.

During the

centuries when rules were rare, wars were not but there was little discussion

about whether or not a war was happening.

There would be debates about the wisdom of going to war or the strategy adopted

but whether or not it was a war was obvious to all. That changed after the Second World War when

the charter of the United Nations was agreed to attempt to ensure force would

never again be used as a means of resolving disputes between nations. That's obviously not been a success but the

implications of the charter have certainly affected the language of conflict,

much now hanging on whether an event is war or something else which merely

looks like war. An early example of the linguistic

lengths to which those waging war (a thing of which they would have boasted) would

go, in the post-charter world, to deny they were at war happened after British,

French and Israeli forces in 1956 invaded Egypt in response to Colonel Gamal

Nasser's (1918–1970; president of Egypt 1954-1970) nationalization of

foreign-owned Suez Canal Company. The

invasion was a military success but it soon became apparent that Israel, France

and Britain were, by any standards, waging an aggressive war and had conspired,

ineptly, to make it appear something else.

The United States threatened sanctions against Britain & France and

the invading forces withdrew. There's

always been the suspicion that in the wake of this split in the Western

Alliance, the USSR seized the opportunity to intervene in Hungary which was

threatening to become a renegade province.

Suez

Canal, 1956.

In the House of Commons (Hansard: 1 November 1956 (vol 558

cc1631-7441631)), the prime minister (Anthony Eden, 1897–1977, UK

prime-minister 1955-1957) was asked to justify how what appeared to be both an

invasion and an act of aggressive war could be in conformity with the Charter

of the United Nations. Just to jog the

prime-minister's memory of the charter, the words he delivered at the UN's

foundation conference in San Francisco in 1945 were read out: “At intervals in history mankind has sought

by the creation of international machinery to solve disputes between nations by

agreement and not by force.” In

reply, Mr Eden assured the house there had been "...no declaration of war by us.", a situation he noted prevailed

for the whole of the Korean War and while there was in Egypt clearly "...a state of armed conflict...", just as

in Korea, "...there was no

declaration of war. It was never admitted that there was a state

of war, and Korea was never a war in any technical or legal sense, nor are we

at war with Egypt now."

Quite

how the comparison with Korea, a police action under the auspices of the UN and authorized by the Security Council (the USSR was boycotting the place at the

time) was relevant escaped many of the prime-minister's critics. The UK had issued an ultimatum to Egypt regarding

the canal which contained conditions as to time and other things; the time

expired and the conditions were not accepted.

It was then clear in international law that in those circumstances the

country which delivers the ultimatum is not entitled to carry on hostilities

without a declaration of war so the question was what legal justification was

there for an invasion? The distinction

between a “state of war" and a

"state of armed conflict",

whatever its relevance to certain technical matters, seemed not to matter in

the fundamental question of the lawfulness of the invasion under international

law. Mr Eden continued to provide many answers

but none to that question.

The aversion

to declaring war continues to this day, the United States, hardly militarily

inactive during the last eight-odd decades, last declared war in 1942 (against Italy, Hungary, Bulgaria & Romania, the latter three apparently at the insistence of the state department which identified certain legal technicalities). There seems no an aversion even to the word, the UK not having had a secretary of state (minister)

for war since 1964 and the US becoming (nominally) pacifist even earlier, the last

secretary of war serving in 1947; the more UN-friendly “defense” the preferred

word on both sides of the Atlantic. In

the Kremlin, Mr Putin (b 1952; prime-minister or president of Russia since

1999) seems also have come not to like the word. While apparently sanguine at organizing “states

of armed conflict”, he’s as reluctant as Mr Eden to hear his “special military

operations” described as “invasions” or “wars” and in a recent legal flourish,

arranged the passage of a law which made “mentioning the war” unlawful.

Not mentioning the war (special military operation): Mr Putin.

The bill

which the Duma (lower house of parliament) & Federation Council (upper

house) passed, and the president rapidly signed into law, provided for fines or imprisonment for up to fifteen years in the Gulag for intentionally spreading “fake

news” or “discrediting the armed forces”, something which includes labelling the

“special military operation” in Ukraine as a “war” or “invasion”. Presumably, given the circumstances, the

action could be described as a “state of armed conflict” and even Mr Putin

seems to have stopped calling it a “peacekeeping operation”; he may have

thought the irony too subtle for the audience.

Those who post or publish anything on the matter will be choosing their

words with great care so as not to mention the war.

However, although Mr Putin may not like using the word “war”,

there’s much to suggest he’s a devotee of the to the most famous (he coined a few)

aphorism of Prussian general & military theorist Carl von Clausewitz

(1780–1831): “War is the continuation of policy with other means.” The view has many adherents and while some

acknowledge its cynical potency with a weary regret, for others it has been a

world view to pursue with relish. In the prison

diary assembled from the huge volume of fragments he had smuggled out of Spandau

prison while serving the twenty year sentence he was lucky to receive for war

crimes & crimes against humanity (Spandauer

Tagebücher (Spandau, the Secret Diaries), pp 451 William Collins Inc,

1976), Albert Speer (1905–1981; Nazi court architect 1934-1942; Nazi minister

of armaments and war production 1942-1945) recounted one of Adolf Hitler’s

(1889-1945; Führer (leader) and German head of government 1933-1945 & head

of state 1934-1945) not infrequent monologues and the enthusiastic concurrence

by the sycophantic Joachim von Ribbentrop (1893–1946; Nazi foreign minister

1938-1945):

"In

the summer of 1939, On the terrace of the Berghof [Hitler’s alpine retreat],

Hitler was pacing back and forth with one of his military

adjutants. The other guests respectfully

withdrew to the glassed-in veranda. But

in the midst of an animated lecture he was giving to the adjutant, Hitler

called to us to join him on the terrace. “They should have listened to Moltke

and struck at once” he said, resuming the thread of his thought, “as soon as France

recovered her strength after the defeat in 1871. Or else in 1898 and 1899. America was at war with Spain, the French were

fighting the English at Fashoda and were at odds with them over the Sudan, and

England was having her problems with the Boers in South Africa, so that she

would soon have to send her army in there. And what a constellation there was in 1905

also, when Russia was beaten by Japan. The

rear in the East no threat, France and England on good terms, it is true, but

without Russia no match for the Reich militarily. It’s an old principle: He who

seizes the initiative in war has won more than a battle. And after all, there was a war on!” Seeing our stunned expressions,

Hitler threw in almost irritably: “There is always a war on. The Kaiser [Wilhelm II

(1859–1941; German Emperor & King of Prussia 1888-1918)] hesitated too

long."

Such

epigrams usually transported Ribbentrop into a state of high excitement. At these moments it was easy to see that he

alone among us thought

he was tracking down, along with Hitler, the innermost secrets of political

action. This time, too, he expressed his

agreement with Hitler with that characteristic compound of subservience and the

hauteur of an experienced traveller whose knowledge of foreign ways still

made an impression on

Hitler. Ribbentrop’s guilt, that is, did

not consist in his having made a policy of war on his own. Rather, he was to blame for using his authority as a

supposed cosmopolite to corroborate Hider’s provincial ideas. The war itself

was first and last Hitler’s idea and work. “That is exactly what neither the Kaiser nor

the Kaiser’s politicians ever really understood,” Ribbentrop was loudly

explaining to everyone. “There’s always

a war on. The difference is only whether the guns are firing or not. There’s war in peacetime too. Anyone who has

not realized that cannot make foreign policy.”

Hider

threw his foreign minister a look of something close to gratitude. “Yes, Ribbentrop,” he said, “yes!" He was visibly moved by having someone in this

group who really

understood him. “When the time comes that I am no longer here, people must keep

that in mind. Absolutely.” And then, as though carried away by his

insight into the nature of

the historical process, he went on: “Whoever succeeds me must be sure to have

an opening for a new war. We never want

a static situation where that sort of thing hangs in doubt In

future peace treaties we

must therefore always leave open a few questions that will provide a pretext. Think of Rome and Carthage, for instance. A

new war was always built right into every peace treaty. That's

Rome for you! That's statesmanship.”

Pleased

with himself, Hitler twisted from side to side, looking challengingly around

the attentive, respectful circle. He was

obviously enjoying the vision of himself beside the statesmen of ancient Rome. When he occasionally compared Ribbentrop with

Bismarck—a comparison I myself sometimes heard him make—he was implying that he

himself soared high above the level of bourgeois nationalistic policy. He saw himself in the dimensions of world

history. And so did we. We went to the

veranda. Abruptly, as was his way, he began talking about something altogether

banal."