Gullwing & Gull-wing (pronounced guhl-wing)

(1) In

aviation, an airplane wing that slants briefly upward from the fuselage and

then extends horizontally outward (ie a short upward-sloping inner section and

a longer horizontal outer section).

(2) Of

doors, a door hinged at the top and opening upward (applied usually to cars but

can be used in aviation, aerospace and architecture).

(3) Anything

having or resembling (extended and partially extended) wings of a gull (and many

other birds).

(4) In

electronic hardware, a type of board connector for a small outline integrated

circuit (SOIC).

(5) In

historic admiralty jargon, a synonym of goose wing (a sail position).

Gull is

from the Middle English gulle, from

the Brythonic, from the Proto-Celtic wēlannā

(seagull) and was cognate with the Cornish guilan,

the Welsh gwylan, the Breton gouelan and the Old Irish faílenn.

The noun Gull was used (in a cook-book!) to describe the shore bird in

the 1400s, probably from the Brythonic Celtic; it was related to the Welsh gwylan (gull), the Cornish guilan, the Breton goelann; all from Old Celtic voilenno-.

Gull replaced the Old English mæw.

The

verb form meaning “to dupe, cheat, mislead by deception" dates from the

1540s, an adaptation by analogy from the earlier (1520) meaning "to

swallow", ultimately from the sense of "throat, gullet" from the

early 1400s. The meaning was the idea of

someone so gullible to “swallow whatever they’re told”. As a cant term for "dupe, sucker,

credulous person", it’s noted from the 1590s and is of uncertain origin

but may be from the verb meaning "to dupe or cheat". Another possibility is a link to the late

fourteenth century Middle English gull

& goll (newly hatched bird" which

may have been influenced by the Old Norse golr

(yellow), the link being the hue of the bird’s down.

Wing

was from the late twelfth century Middle English winge & wenge (forelimb

fitted for flight of a bird or bat), applied also to the part of certain

insects which resembled a wing in form or function, from the Old Norse vængr (wing of a bird, aisle etc) from the

Proto-Germanic wēinga & wēingan-. It was cognate with the Danish vinge (“wing”), the Icelandic vængur (wing), the West Frisian wjuk (wing) and the Swedish vinge (“wing”), of unknown origin but

possibly from the Proto-Germanic we-ingjaz

( a suffixed form of the primitive Indo-European root we- (blow), source of the Old English wawan (to blow). It replaced

the native Middle English fither,

from the Old English fiþre & feðra (plural (and related to the modern

feather)) from the Proto-Germanic fiþriją,

which merged with fether, from the

Old English feþer, from the

Proto-Germanic feþrō). The meaning "either of two divisions of

a political party, army etc dates from circa 1400; the use in the architectures

was first recorded in 1790 and applied figuratively almost immediately. The slang sense of earn (one's) wings is

1940s, from the wing-shaped badges awarded to air cadets on graduation. To be

under (someone's) wing "protected by (someone)" is recorded from the early

thirteenth century; the phrase “on a wing and a prayer” is title of a 1943 song

about landing a damaged aircraft.

A Gull in flight (left), inverted gull-wing on 1944 Voight Corsair (centre) & gull-wing on 1971 Piaggio P.136 (Royal Gull) (right).

In aviation, the design actually pre-dates powered flight (1903) by half a millennium, appearing in the speculative drawings of flying machines by Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) and others, an inevitable consequence of being influenced by the flapping wings of birds. There were experiments, circa 1911, to apply the gull-wing principle to some of the early monoplanes in a quest to combine greater surface area with enhanced strength but it wasn’t until the 1920s it began widely to be used, firstly in gliders for some aerodynamic advantage and later, powered-aircraft. In powered aircraft, the gull-wing offered little aerodynamically but had structural advantages in that it allowed designers more easily to ensure (1) increasingly larger propellers would have sufficient clearance, (2) undercarriage length could be reduced (and consequently strengthened) and (3) wing-spans could slightly be reduced, a thing of great significance when operations began on aircraft carriers, the gull-wing being especially suited to the folding-wing model. Depending on the advantage(s) sought, designers used either a classic gull-wing or the inverted gull-wing. The correct form is for all purposes except when applied to the the (1954-1957) Mercedes-Benz 300 SL coupé is the hyphenated gull-wing; only the 1950s Mercedes-Benz are called Gullwings.

Cars with gull-wing doors had been built before Mercedes-Benz

started making them at (small) scale and the principle was known in both aviation and marine architecture.

One was the 1945 Jamin-Bouffort JB, the creation of French aeronautical

engineer Victor-Albert Bouffort (1912-1995) who had a long history of clever,

practical (and sometimes unappreciated) designs. The Jamin-Bouffort JB

was a relatively small three-wheeler built using some of the techniques of construction used in

light aircraft, the gull-wing doors the most obvious novelty. Anticipating the 1950s boom in micro-cars,

there was potential but with European industry recovering from the war, most

effort was directed to resuming production of pre-war vehicles using surviving tooling

and there was little interest in pursuing anything which required development

time. Monsieur Bouffort would go on to

design other concepts ahead of their time, some of his ideas adopted by others

decades after his prototypes appeared.

In 1939, Jean

Bugatti drew up plans for the Type 64, a vehicle with gull-wing doors, his

sketches an example of the great interest being shown by European manufacturers in aerodynamics, then called usually streamlining.

Although two Type 64s were completed in 1939, neither used the gull-wing doors and it would be another eighty-odd years before Bugatti’s design was realised

when collector & president of the American Bugatti Club, Peter Mullin (b

1941), arranged the fabrication of the coachwork, based on the original

drawings. Built in exactly the same way

craftsmen would have accomplished the task in 1939, the body was mounted on

the surviving Type 64 chassis (64002), united for the first time with what Jean

Bugatti called papillon (butterfly)

doors which all (except the French) now call gull-wings.

Mercedes-Benz and the gull-wing.

By 1951, although the Wirtschaftswunder (the post-war German “economic miracle”) still lay ahead, structural changes (the most important being the retreat by the occupying forces in the western zones from the punitive model initially adopted and the subsequent creation in 1948 of the stable deutschmark), had already generated an economy of unexpected strength and Mercedes-Benz was ready to make a serious return to the circuits. Because the rules then governing Formula One didn’t suit what it was at the time practical to achieve, the first foray was into sports car racing, the target the ambitious goal of winning the Le Mans 24 hour race, despite a tight budget which precluded the development of new engines or transmissions and dictated the use of as much already-in-production as possible.

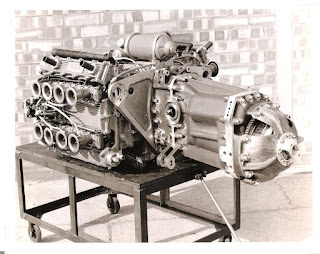

It was the use of a production car engine designed not for ultimate power but smoothness, reliability and a wide torque band which ultimately dictated the use of the gull-wing doors. The engine was the 3.0 litre (183 cubic inch) M186 straight-six used in the big 300 limousines and its two door derivatives, of advanced design by the standards of the time but also big, tall and heavy, attributes not helpful to race-car designers who prefer components which are compact, light and able to be mounted low in a frame. A new engine not being possible, the factory instead created a variation, the M194, which used the triple-carburetor induction of the 300S coupés in an improved cylinder head, the innovation being the iron-block now lying at a 50o angle, thereby solving the problem of height by allowing it to be installed while canted to the side, permitting a lower bonnet line. Using the existing gearbox, it was still a heavy engine-transmission combination, especially in relation to its modest power-output and such was the interest in lightness that, initially, the conventional wet-sump was retained so the additional weight of the more desirable dry-sump plumbing wouldn’t be added. It was only later in the development-cycle that dry-sump lubrication was added.

The

calculations made suggested that with the power available, the W194 would be

competitive only if lightness and aerodynamics were optimized. Although the relationship between low-drag

and down-force were still not well-understood, despite the scientific

brain-drain to the US and USSR (forced and otherwise) in the aftermath of the

war, the Germans still had a considerable knowledge-base in aerodynamics and this

was utilized to design a small, slippery shape into which the now slanted

straight-six would be slotted. There

being neither the time nor the money to build the car as a monocoque, the

engineers knew the frame had to be light.

A conventional chassis was out of the question because of the weight and

they knew from the pre-war experience of the SSKL how expensive and difficult

it was to reduce mass while retaining strength. The solution was a space-frame, made from tubular

aluminum it was light, weighing only between 50-70 kg (110-155 lb) in it’s

various incarnations yet impressively stiff and the design offered the team to

opportunity to use either closed or open bodies as race regulations required.

However,

as with many forms of extreme engineering, there were compromises, the most

obvious of which being that the strength and torsional rigidity was in part

achieved by mounting the side tubes so high that the use of conventionally

opening doors was precluded. In a race

car, that was of no concern and access to the cockpit in the early W194s was

granted by what were essentially top-hinged windows which meant ingress and

egress was not elegant and barely even possible for those of a certain girth

but again, this was though hardly to matter in a race car. In this form, the first prototypes were built,

without even the truck-like access step low on the flanks which had been in the

original plans.

Actually,

it turned out having gull-wing windows instead of gull-wing doors did

matter. Although the rules of motorsport’s

pettifogging regulatory body, the Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile (the FIA; the International

Automobile Federation) were silent on the types and direction of opening doors and, in the pre-war era they had tolerated some essentially fake doors, their

scrutineers still raised objections during inspection for the 1952 Mille Miglia. The inspectors were forced to relent when unable to

point to any rule actually being broken but it was clear they’d be out for

revenge and the factory modified the frame to permit doors extending down the

flanks, thereby assuming the final shape which would come to define the

gull-wing door. Relocating some of the

aluminum tubing to preserve strength added a few kilograms but forestalled any

retrospective FIA nit-picking. To this

day, the FIA's legions of bureaucrats seem not to realise why they’ve for so long been

regarded as impediments to competition and innovation.

First tested on the Nürburgring and Hockenheimring in late 1951, the W194, now dubbed 300 SL for promotional purposes, was in March 1952 presented to the press on the Stuttgart to Heilbronn autobahn. In those happy days, there was nothing strange about demonstrating race cars on public highways. The SL stood for Super Leicht (super light), reflecting the priority the engineers had pursued. Ten W194s were built for the 1952 season and success was immediate, second in the Mille Miglia; a trademark 1-2-3 result in the annual sports car race in Bern and, the crowning achievement, a 1-2 finish in the twenty-four hour classic at Le Mans. Neither usually the most powerful nor the fastest car in the races it contested, the 300 SL nevertheless so often prevailed because of a combination of virtues. Despite the heavy drive-train, it was light enough not to impose undue stress on tyres, brakes or mechanical components, the limousine engine was tough and durable and the outstanding aerodynamics returned surprising good fuel economy; in endurance racing, reliability and economy compensate for a lot of absent horsepower.

As a footnote (one to be noted only by the subset of word nerds who delight in the details of nomenclature), for decades, it was said by many (even normally reliable sources) that SL stood for Sports Leicht (sports light) and the history of the Mercedes-Benz alphabet soup was such that it could have gone either way (the SSKL (1929) was the Super Sports Kurz (short) Leicht (light)) and from the 1950s on, for the SL, even the factory variously used Sports Leicht and Super Leicht. It was only in 2017 it published a 1952 paper (unearthed from the corporate archive) confirming the correct abbreviation is Super Leicht. Sports Leicht Rennsport (Sport Light Racing) seems to be used for the the SLRs because they were built as pure race cars, the W198 and later SLs being road cars but there are references also to Super Leicht Rennsport. By implication, that would suggest the original 300SL (the 1951 W194) should have been a Sport Leicht because it was built only for competition but given the relevant document dates from 1952, it must have been a reference to the W194 which is thus also a Sport Leicht. Further to muddy the waters, in 1957 the factory prepared two lightweight cars based on the new 300 SL Roadster (1957-1963) for use in US road racing and these were (at the time) designated 300 SLS (Sports Leicht Sport), the occasional reference (in translation) as "Sports Light Special" not supported by any evidence. The best quirk of the SLS tale however is the machine which inspired the model was a one-off race-car built by Californian coachbuilder ("body-man" in the vernacular of the West Coast hot rod community) Chuck Porter (1915-1982). Porter's SLS was built on the space-fame of a wrecked 300 SL gullwing (purchased for a reputed US$500) and followed the lines of the 300 SLR roadsters as closely as the W198 frame (taller than that of the W196S) allowed. Although it was never an "official" designation, Porter referred to his creation as SL-S, the appended "S" standing for "scrap".

Unlike their neighbours in Stuttgart, Porsche have never had any doubt what they meant by "SL". After the end of World War II (1939-1945), it took some time for Herr Professor Ferdinand Porsche (1875–1951) to extricate himself from the clutches of the allied authorities which had arrested him as a war criminal but once free, he moved to the town of Gmünd in north-west Austria where he embarked on a project to build his own cars, the first being a small roadster using many components from the Volkswagen (Type 1; Beetle) with which he was familiar. However, upon consideration of the realities of even small-scale series production and the market potential of various body styles, it was decided to create a rear-engined, closed coupé and in just under three months, Porsche’s small team designed what came to be known as the “Gmünd Coupé”, the first leaving the modest works in June 1948. By 1950 over 50 had been built (including a half-dozen-odd cabriolets), all with hand-formed aluminum bodies and the layout and shape remains identifiable the in rear-engined (and the mid-engined Boxer and Cayman) Porsches produced in 2025.

When in 1950 Porsche relocated his operation to Zuffenhausen, production resumed with bodies of steel rather than aluminum but eleven of the Gmünd chassis were shipped north and used by the factory for their competition programme; they were converted to Sport Leicht (Sports Light) specification and named 356 SL (internally the 356/2 3000 series), fitted with 1086 cm3 (66 cubic inch), air-cooled, flat four engines (rated at 46 horsepower), enlarged fuel tanks, louvered quarter-window covers, fender skirts (spats), streamlined belly fairings and an aluminium body. The factory entered three 356 SLs in the 1951 Le Mans 24 hour endurance classic and while two crashed, one won the 751-1100 cm3 class (46-67 cubic inch).

One final adventure for the year yielded a perhaps unexpected success. In November 1952, the factory entered two coupés and two roadsters in the third Carrera Panamericana Mexico, a race of 3100 kilometres (1925 miles) over five days and eight stages, their engines now bored out to 3.1 litres (189 cubic inches) increasing power from 175 bhp (130kw) to 180 (135). The cars finished 1-2-3 although the third was disqualified for a rule violation and the winning car endured the intrusion at speed of a vulture through the windscreen. Unlike the 300 SL, the unlucky bird didn’t survive. There was however one final outing for the W194. In 1955 it won the Rally Stella Alpina, the last time the event would be run in competitive form, one of many cancelled in the wake of the disaster at Le Mans that year in which 84 died and almost two-hundred injured. Coincidently, that accident involved the W194’s successor, the 300 SLR.

The 300

SL was re-engineered for the 1953 season, the bodywork now made from magnesium,

lighter even than aluminum, the design of which had seen the car return to the

wind-tunnel after which it gained a revised front section which not only

reduced drag but also improved cooling by optimizing airflow to the radiator

and engine compartment. Power rose

too. Again drawing from wartime

experience with the DB60x V12 aero-engine used in many German warplanes, direct

fuel-injection was introduced which boosted output from 180 bhp (135 kw) to 215

bhp (158 kW). Nor were the underpinnings

neglected, the rear suspension design improved (somewhat) with the addition of the

low-pivot single-joint swing axle (which would later appear on some production

300 SLs) while the transmission was flanged on the rear axle, not quite a transaxle

but much improving the weight distribution. The wheelbase was shortened by 100 millimetres

(4 inches) and 16-inch wheels were adopted.

Even disk brakes were considered but the factory judged them years from

being ready and it wouldn’t be until 1961 that they appeared on a

Mercedes-Benz, more than half a decade after others had proved the technology

on road and track. There was however one

exception to that, a disc brake had been installed between propeller shaft and

differential on the high-speed truck built in 1954 to carry the Grand

Prix cars between the factory and circuits in Europe.

The

revised 300 SL however was never raced, the factory’s attention now turning to

the Formula One campaign which, with the W196, would so successfully be

conducted in 1954-1955, an off-shoot of which would be the W194’s replacement,

the W196S sports car which would be based on the Grand Prix machine and dubbed,

a bit opportunistically, the 300 SLR (Sport

Leicht Rennen (Sport Light-Racing)).

Such was the impression made by the futuristic W194 that it would

inspire production of the road-going 300 SL Gullwing (W198), 1400 of which were

built during 1954-1957 (including 29 with aluminium bodies).

Although the public found them glamorous, the

engineers at Mercedes-Benz had never been enamoured by the 300 SL’s gull-wing

doors, regarding them a necessary compromise imposed by the high side-structure

of the space-frame which supported the body.

Never intended for use on road-cars, it was the guarantee of the US

importer of Mercedes-Benz to underwrite the sale of a thousand gull-wing coupés

that saw the 300 SL Gullwing enter production in 1954. The sales predictions proved accurate and of

the 1400 built, some 80% were delivered to North American buyers. The W198 300SL was the model which became

entrenched in the public imagination as “the Gullwing” and it’s the only

instance where the word doesn’t need to be hyphenated. Glamorous those doors may have been, they did

impose compromises. The side windows

didn’t roll down, ventilation was marginal and air-conditioning didn’t exist;

in a hot climate, one really had to want to drive a Gullwing. There was also the safety issue, some drivers

taking the precaution of carrying a hammer in case, in a roll-over, the

inability to open the doors made the windscreen the only means of escape and

roll-overs were perhaps more likely in a Gullwing than many other machines, the nature of the swing axles sometimes inducing unwanted behavior in what was

one of the fastest cars on the road although, in fairness, on the tyres available in the 1950s that was less of an issue than it would become on later,

stickier rubber.

In the US in 1956, a "fully optioned" Gullwing would have been invoiced at US$8894.00 and apart from the car itself, some of those options would proved a good investment, items like the knock-off wheels adding by the 2020s at least tens of thousands to the selling price and even the fitted luggage attracts a premium. The options affecting the mechanical specification (notably the camshaft and choice of final drive ratio) had a significant influence on the character of the car, the former raising the rated horsepower from 220 to 240 and in its more powerful form the top speed would have been 140-155 mph (225-250 km/h) depending on the gearing. Those serious about speed could opt for the "package" of the aluminum body with "full competition equipment" including the Rudge wheels and upgraded engine & suspension, supplied with two complete axles in a choice of gear ratios. That package listed at US$9300.00 which in retrospective was another reasonable investment given the aluminum Gullwing from Rudi Klein's "junkyard collection" sold at auction in October 2024 for US$9,355,000 (an that for a vehicle needing restoration). Still, all things are relative and average annual income in the US in 1956 was about US$3600 and while it was possible to buy what would now be called a "house & land package" for around US$8000, the typical house sold for more than twice that. The 300 SL would still have been a sound investment because although one would have incurred insurance, maintenance, running and storage costs over the decades, a well maintained, original, 1956 aluminum Gullwing would now sell for well in excess of US$12 million while US$9600 placed in the S&P 500 index would by 2024 be worth some US$9.4 million (assuming all dividends were re-invested). There have been better investments than aluminum Gullwings but not many.

The 300 SLR (W196S) was a sports car, nine of which were built to contest the 1955 World Sportscar Championship. Essentially the W196 Formula One car with the straight-eight engine enlarged from 2.5 to 3.0 litres (152 to 183 cubic inches), the roadster is most famous for the run in the 1955 Mille Miglia in Italy which was won over a distance of 992 miles (1597 km) with an average speed of almost 100 mph (160 km/h); nothing like that has since been achieved. There's infamy too attached to the 300 SLR; one being involved in the catastrophic crash and fire at Le Mans in 1955.

Two of the 300 SLRs were built with coupé bodies, complete with gull-wing doors. Intended to be used in the 1955 Carrera Panamericana Mexico, they were rendered instantly redundant when both race and the Mercedes-Benz racing programme was cancelled after the Le Mans disaster. The head of the programme, Rudolf Uhlenhaut (1906-1989), added an external muffler to one of the coupés, registered it for road use (such things were once possible when the planet was a happier place) and used it for a while as his company car. It was then the fastest road-car in the world, an English journalist recording a top speed of 183 mph (295 km/h) on a quiet stretch of autobahn but Herr Uhlenhaut paid a price for the only partially effective muffler, needing hearing aids later in life. Two were built (rot (red) & blau (blue), the names based on their interior trim) and for decades they remained either in the factory museum or making an occasional ceremonial appearance at race meetings. However, in a surprise announcement, in June 2022 it was revealed rot had been sold in a private auction in Stuttgart for a world-record US$142 million, the most expensive car ever sold. The buyer's identity was not released but it's believed rot is destined for a collection in the Middle East. It's rumoured also the same buyer has offered US$100 million should an authentic 1929 Mercedes-Benz SSKL ever be uncovered.

1970 Mercedes-Benz C-111 (1968-1970 (Wankel versions)).Although the C-111 would have a second career in

the late 1970s in a series of 5-cylinder diesel and V8 petrol engined cars used

to set long-distance endurance records, its best remembered in its original

incarnation as the lurid-colored (safety-orange according to the

factory) three and four-rotor Wankel-engined gullwing coupés, sixteen of which

were built. The original was a pure

test-bed for the Wankel engine in which so many manufacturers once had so much

hope. The first built looked like a

failed high-school project but the second and third versions were both finished

to production-car standards with typically high-quality German workmanship. Although from the school of functional

brutalism rather than the lovely things they might have been had styling been

out-sourced to the Italians, the gull-winged wedges attracted much attention

and soon cheques were enclosed in letters mailed to Stuttgart asking for one. The cheques were returned; apparently there

had never been plans for production even had the Wankel experiment proved a

success. The C-111 was fast, the

four-rotor version said to reach 300 km/h (188 mph), faster than any production

vehicle then available.

The C112 was an experimental mid-engined concept car built in

1991. Designed to be essentially a

road-going version of the Sauber-built C11 Group C prototype race car developed

for the 1990 World Sports-Prototype Championship, it was powered by the 6.0

litre (366 cubic-inch) M120 V12 used in the R129 SL and C140/W140 S-Class

variously between 1991-2001. The C112

does appear to have been what the factory always claimed it was: purely a test-bed for technologies such as the electronically-controlled

spring & damper units (which would later be included on some models as ABC

(active body control)), traction control, rear wheel steering, tyre-pressure

monitoring and distance-sensing radar. As an indication it wasn't any sort of prototype intended for production, it offered no luggage space but, like the C111 twenty years earlier,

it’s said hundreds of orders were received. It was 1991 however and with the world in the depths of

a severe recession, not even that would have been enough for a flirtation with thoughts of

a production model. After the C112,

thoughts of a gull-wing were put on ice for another two decades, the SLR-McLaren

(2003-2009) using what were technically “butterfly” door, hinged from the

A-pillars.

The factory’s most recent outing of the gull-wing door, the SLS, which used the naturally aspirated 6.2 litre (379 cubic inch) M159 DOHC V8, was produced between (2010-2014), a roadster version also available. To allay any doubt, it was announced at the time of release that SLS stands for Super Leicht Sport (Super Light Sport) although such things are relative, the SLS a hefty 1600-odd kg (3,500 lb) although, in fairness, the original Gullwing wasn’t that much lighter and the SLS does pack a lot more gear, including windows which can be opened and air-conditioning. In the way of modern marketing, many special versions were made available during the SLS’s relatively short life, even an all-wheel-drive electric version with a motor for each wheel. Such is the lure of the gull-wing motif for Mercedes-Benz, it’s unlikely the SLS will be the last and a high-priced revival is expected to become a feature of the marketing cycle every couple of decades but we're unlikely to see any more V8s or V12s unless perhaps as a swan-song, AMG indicating recently they expect their 4.0 litre (244 cubic inch) V8 to remain in production for another ten years, Greta Thunberg (b 2003) and her henchmen the humorless EU bureaucrats permitting.

Lindsay Lohan at the Nicholas Kirkwood (b 1980; shoe designer) catwalk show with a prop vehicle (one of the gull-wing DMC DeLoreans modified closely to resemble the one used in the popular film Back to the Future (1985)), London Fashion Week, 2015.

Such was the allure of the 300 SL’s gull-wing doors that in the shadow they’ve cast for seventy-odd years, literally dozens of cars have appeared with the features, some of questionable aesthetic quality, some well-executed and while most were one-offs or produced only in small runs, there’s been the occasional (usually brief) success and of late some Teslas have been so equipped and with the novelty of them being the back doors, the front units conventionally hinged. Tesla calls them “falcon wings” because the design was influenced by the bird. However, the biomimicry was (for obvious reasons) not an attempt to gain the aerodynamic advantages of the falcon’s wing shape which affords exceptional maneuverability in flight but simply an adoption of the specific bone structure. Unlike the fixed structure of the classic gull-wing door, the Tesla’s falcon-wing is fitted with an additional central joint which permits them to be opened in cramped spaces, aiding passenger ingress and egress. Some Tesla engineers have however admitted the attraction of them as way to generate publicity and (hopefully) attract sales may have been considered during the design process.

Bricklin SV-1 (1974-1975, left) and DMC DeLorean (1981-1983, right).

Two of the best known of the doomed gull-wing cars were the Bricklin SV1 and the DeLorean, both the creations of individuals with interesting histories. Malcolm Bricklin’s (b 1939) first flirtation with the automotive business was his introduction into the US market of the Subarus, built by the Japanese conglomerate Fuji Heavy Industries. Having successfully imported the company’s scooters for some years, the model Mr Bricklin in 1968 chose was the 360, a tiny, egg-shaped device which had been sold in Japan for a decade, the rationale underlying his selection being it was so small and light it was exempt from just about any regulations. Although really unsuited to US motoring conditions it was (at US$1300) several hundred dollars cheaper than a Volkswagen Beetle and had a fuel consumption around a third that delivered by even the less-thirsty US-built cars so it found a niche and some ten-thousand were sold before that gap in the market was saturated. Ever imaginative, Mr Bricklin then took his hundreds of unsold 360s and re-purposed them essentially as large dodgem-cars, renting unused shopping-mall car-parks as ad-hoc race tracks and offering “laps” for as little as $US1.00. He advertised “no speed limits” to attract the youth market but given the little machines took a reported 56 seconds for the 0-60 mph (0-100 km/h) run, reaching any state's legal limit in a car-park would have been a challenge. Mr Bricklin achieved further success with Subaru’s more conventional (in a front wheel drive (FWD) context) 1000 and the corporation would later buy out his US interests for was thought to be a most lucrative transaction for both parties.

His eponymous gull-winged creation was the SV-1 which, although nominally positioned as a “sports car” was marketed also as a “safety-vehicle” (hence the SV). It certainly contained all of the safety features of the time and in that vein was offered mostly in lurid “high visibility” colors although the prototypes for an up-market “Chairman” version were displayed in more restrained black or white. It was ahead of its time in one way, being fitted with neither ash-trays nor cigarette lighters, Mr Bricklin not approving of smoking and regarding the distractions of lighting-up while at the wheel a safety hazard. Whether in stable conditions the car could have succeeded is speculative but the timing was extraordinarily unlucky. The V8-powered car arrived on the market in 1974 shortly after the first oil shock saw a spike in the price of gasoline and in the midst of the recession and stagflation which followed in the wake. Between its introduction and demise, the costs of the SV1 more than doubled and there were disruptions to the production process because supply problems (or unpaid bills, depending on who was asked) meant the AMC engine had to be replaced with a Ford power-plant. By the time production ended, only some 3000 had been built, but, not discouraged, Mr Bricklin would go on to import Fiat sports cars and the infamous Yugo before being involved with a variety of co-ventures with Chinese partners.

John DeLorean (1925–2005) was a genuinely gifted engineer who emerged as one of the charismatic characters responsible for some of the memorable machines General Motors (GM) produced during its golden age of the 1950s & 1960s. Under Mr DeLorean’s leadership, Pontiac in 1964 released the GTO which is considered (though contested by some) the first “muscle car” and the one responsible for the whole genre which would flourish for a crazy half-dozen years and in 1969 the Grand Prix which defined a whole market segment. Apparently, the Grand Prix, produced at a low cost and sold at a high price was one of the most profitable lines of the era. Given this, Mr DeLorean expected a smooth path to the top of GM but for a variety of reasons there were internal tensions and in 1973 he resigned to pursue his dream of making his own car. It took years however to reach fruition because the 1970s were troubled times and like the Bricklin SV1, the DeLorean Motor Company’s (DMC) gull-winged DeLorean was released into a world less welcoming than had been anticipated. By 1981, the world was again in recession and the complicated web of financing arrangements and agreements with the UK government to subsidize production could have worked if the design was good, demand was strong and the product was well-built, none of which was true.

As the inventory of unsold cars grew, so did the debt and desperate for cash, Mr DeLorean was persuaded (apparently without great difficulty) to become involved in the cocaine trafficking business which certainly offered fast money but his co-conspirator turned out to be an FBI informant who was a career criminal seeking a reduced sentence (on a unrelated matter) by providing the bureau with “a big scalp”. At trial in 1984, Mr DeLorean was acquitted on all charges under the rule of "entrapment" but by then DMC was long bankrupt. In the years since, the car has found a cult following, something due more to its part in the Back to the Future films than any dynamic qualities it possessed. It was competent as a road car despite the rear-engine configuration and the use of an uninspiring power-plant but, apart from the stainless-steel bodywork and of course the doors, it had little to commend it although over the years there have been a number of (ultimately aborted) revivals and plans remain afoot for an electric gull-wing machine using the name to be released in 2025.