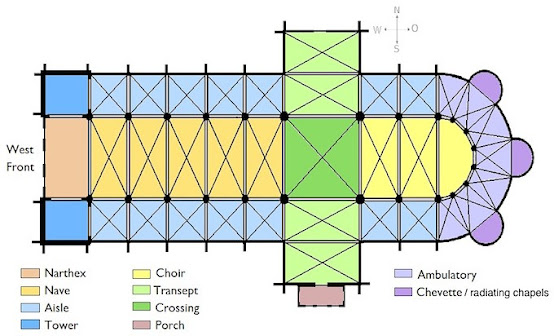

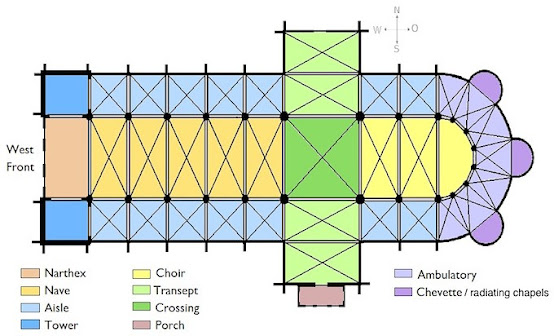

Narthex (pronounced nahr-theks)

(1) In church architecture, a portico (enclosed passage) at the west end of a basilica or church, usually at right

angles to the nave and located between the main entrance and the nave.

(2) In botany, a taxonomic genus within the family

Apiaceae (umbelliferous plants), now included in Ferula, Narthex asafoetida and

thus obsolete.

1665-1675:

From the Medieval Latin narthex, from the Medieval

Greek narthex (enclosed porch, enclosure (the earlier meaning was “box”), from the Ancient Greek νάρθηξ (narthēx) (giant fennel, scourge (and later

“casket” (the Modern Greek νάρθηκας (nárthikas)),

and, on the basis of the suffix, probably a pre-Greek word. The connection between the giant fennel plant

and boxes is that the fibre from the stems of the plant was used to make boxes. In Greek, the word was linked also to νάρδος

(nárdos) (nard plant, spikenard,

nardin, muskroot). The Modern Greek νάρθηκας (narthekas) long

ago relinquished the early senses and now means either the feature in church

architecture or the brace of a sprained

wrist or sling of a broken arm. The plant

was well known in Greek mythology. In the

Θεογονία (circa 730–700 BC) (Theogonía

(the genealogy or birth of the gods)), known in the West as The Theogony, an epic poem of a thousand-odd

lines by the (8th-7th century BC) poet Hesod, it was in hollow

fennel stalks that Prometheus conveyed fire from Heaven to Earth. In Armenia the name for a narthex is gavit.

The adjectival form was narthecal

and the plural either narthexes or narthices,

the English form preferable for most purposes.

Narthexs

were part of many early Christian and Byzantine basilicas and churches, located

traditionally to the west of the nave and functioned (1) as a lobby area and

(2) as the place where penitents

were required to remain. Although

the archaeological record suggests there may have been some early churches with

annexes or even small separate structures located nearby which fulfilled the

latter function, narthexes seem quickly to have been integrated. That means that structurally and

architecturally, a narthex was part of the building but theologically was not,

its purpose being to permit those not entitled to admission as part of the

congregation (mostly catechumens and penitents) nevertheless to hear the

service and (hopefully) be encouraged to pursue communion.

For

ceremonies other than services, the narthex was otherwise a functional space, the

church’s baptismal font often mounted there and in some traditions (both

Eastern & Western) worshipers would sometimes anoint themselves and their

children with a daub of holy water before stepping foot in the nave and some

branches of the Orthodox Church use the narthex for funeral ceremonies. There were also architectural variations in

the early churches which persisted in larger building and cathedrals, the

narthex divided in two, (1) an esonarthex (inner narthex) between the west wall

and the body of the church proper, separated from the nave and aisles by a wall,

trellis or some other means and (2) an external closed space, the exonarthex

(outer narthex), a court in front of the church façade with a perimeter defined

by on all sides by colonnades.

In the

Western Church, reforms removed the requirement to exclude from services those

who were not full members of the congregation which of course meant the narthex

was rendered technically redundant. However, the shape churches had assumed with a

narthex included had become part of the tradition of the Church so architects

continued to include the space, both as part of the nave structure and

something semi-separated. They attracted

a number of names, borrowed mostly from secular buildings including vestibule, porch,

foyer, hallway, antechamber, anteroom,

entrance, entry, entryway, gateway, hall, lobby, portal & portico, the

choice dictated sometimes by local tradition, sometimes by the nature of construction

and sometimes, it seems to have been entirely arbitrary. In the Eastern Orthodox Church, the esonarthex

and exonarthex retained distinct liturgical functions, some rituals terminating

in the exonarthex while services still exclusively penitential services are usually

chanted in the esonarthex. In dialectal

northern English, the casual term for the penitents forced to remain in the narthex

was “the narts”.

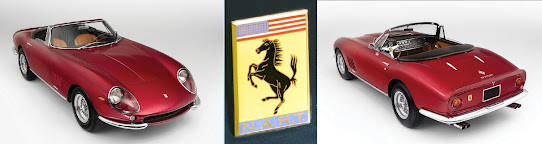

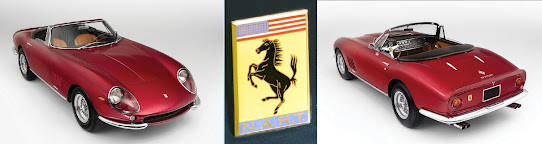

The

NART Ferrari spiders

1966 Ferrari 275 GTS

Although

Ferrari produced the 275 GTB (berlinetta (coupé)) (1964-1968) and 275 GTS (spider

(roadster)) (1964-1966) in unison with substantially the same mechanical

specification, the two had completely different coachwork, sharing not one external

panel. Styled by Pininfarina, the 275

GTS, elegant and well-proportioned, recalled the earlier 250 Cabriolets and buyers

appreciated the sophistication of the improved specification but Luigi Chinetti

(1901-1994), Ferrari's North American distributer, remembering the sensuous lines

of the 250 California Spider (1957-1960), asked the factory for a run of

spiders (roadsters) based on the 275 GTB.

1960 Ferrari 250 California Spider

Ferrari

commissioned its traditional coachbuilder, Carrozzeria Scaglietti, to produce

the series and in 1967, the first tranche of ten of a planned twenty-five was

completed and delivered to the United States.

The spiders were based on the newly-released 275 GTB/4 which included a

number of refinements to the original series, most notably the twin-cam heads,

the factory rating the 3.3 Litre (201 cubic inch) V12 at 300 horsepower, a lift

of 20 over the earlier single-cam engines.

Because Chinetti’s competition department was called the North American

Racing Team (NART), the ten roadsters have always been referred to as the “NART

Spiders” and although the factory never adopted the designation, Chinetti added

to the tail of each a small cloisonné badge with the team's logo. Interestingly, the factory also continued to

list the cars as 275 GTB/4s, even though the usual naming convention would have

been to designate them as 275 GTS/4s, a hint perhaps from Ferrari that it

really wasn’t their idea.

1967 Ferrari 275 GTB/4

The

addition of the badge, an unusual addition to anything from Scaglietti

workshops, was not unreasonable given the spiders were very much a

co-production, Chinetti receiving technical assistance and the precious benefit

of official status from the factory but it was made clear that financial

responsibility for the project lay exclusively with the US operation which

would be required to pay for each prior to delivery. On that basis things proceeded but, modified

from production 275 GTB/4’s with (then typically Italian) labour-intensive coach-building

techniques, the spiders were expensive and sales were slow, American buyers

more seduced by Ferrari's new and more luxuriously trimmed and cheaper 330 GTS; even then

air-conditioning was a persuasive inducement and the more spartan NARTs languished

for some months in Chinetti’s showroom waiting for someone with a longing for the

ways things used to be done. As a

consequence, it was only that first run of ten which was built but they’ve

since become highly prized by collectors, NART #10709 in August 2013 selling at

auction for US$27.5 million (including commission) at RM Sotheby's in Monterey,

California.

1969 Ferrari 275 GTB/4 NART Spider

Daytona 24 Hours, 1967: First-Ferrari 330 P3/4 (#23; Chris Amon & Lorenzo Bandini),

Second-Ferrari 330 P4 (#24; Mike Parkes & Ludovico Scarfiotti and

Third-Ferrari 412 P (#26; Pedro Rodriguez & Jean Guichet.

However,

despite the modest demand for the NART spiders, Ferrari must have been

convinced the concept was viable with full factory backing and when, in 1968,

the 275 GTB/4 was replaced with the 365 GTB/4 (1968-1973), a companion spider

was listed as an official model, again built by Carrozzeria Scaglietti. This model came to be known as the Daytona in

recognition of Ferrari’s 1-2-3 finish in the 1967 24 Hours of Daytona even

though the cars which contested the race were different models, the connection

being some photographs from the race which were used in promotional material when the

365 GTB/4 was released. It was the first

new model since the 1-2-3 finish and the name stuck, an attachment about which Ferrari seemed never much enthused although views seem to have

softened over the years and "Daytona" appears now even on the corporate website. The V12 was now 4.4 litres (268 cubic inches)

and generating some 340-355 horsepower (depending on market) although the

figure on which many fixated was the claimed top speed of 174 mph (280 km/h), the

need to out-pace the mark of 171 mph (275 km/h) set by the Lamborghini Miura P400 in 1966 said to

be one of the design objectives. Quite a

few verified Ferrari’s claim; few attempted it in the somewhat trickier to handle Miura although contemporary reports confirmed the factory's number. The Ferrari might actually have gone faster, given enough road. Luigi Chinetti (1901–1994), who drove the competition version of the Daytona in the 1971 Le Mans 24 hour classic (the last year before the 3.7 mile (6 km) Mulsanne straight was spoiled by the chicanes the FIA imposed) reported than on Mulsanne it never actually stopped accelerating. Remarkably, the Daytona finished fifth, even winning the mysterious Index of Thermal Efficiency. Whatever it was, Ferrari must have been content with the thing's terminal velocity but Lamborghini wanted bragging rights and the more powerful Miura P400 S debuted in 1969 with a claim of 180 mph (290 km/h) which Autosport magazine in 1970 almost matched, clocking 288.6 km/h (179.3 mph). That turned out to be the decade's high-water mark, the succeeding P400 SV more powerful still but a little slower because the aerodynamics were slightly compromised by the need to add a little width to accommodate some needed improvements and the use of fatter tyres which absorbed a surprising amount of energy. It would be many years before a production car went faster than the P400 S.

1972 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 (Daytona)

What

was however learned from 275 NART experience was that the customers had become sybarites

who wanted cars which looked like the austere roadsters of old but fitted with

the accruements of modernity, air conditioning, power steering and electric

windows. On that basis the Daytona entered

production and in what was by then a much more competitive market, the approach

was vindicated, the Daytona close to doubling the sales of its predecessor,

including 122 spiders. Intriguingly, within

a few years of the end of Daytona production ending, the realization hit that

there wouldn’t again be something like the 365 GTS/4, the days of the big,

front-engined V12s thought over and even if one returned, the feeling in the

1970s was that government regulations would be there would be no more roadsters

and interest in Daytona spiders began to spike. With only 122 produced, the math of the supply-demand

curve was predictable and prices of spiders soared above the berlinetta, the

factory having made more than ten times as many of them.

1971 Ferrari 365 GTS/4 (Daytona)

Thus stimulated

was the roofectomy business which had long been part of the coach-building trade

but few conversions were potentially as lucrative as a Daytona. Done properly, the results could be

satisfactory but, beyond the roof, there were a number of differences between

the two and not all were done properly.

However it’s done, a genuine Scaglietti spider is going to be worth some

multiple of a conversion in similar condition, which may now attract little premium

over a berlinetta, originality now more of a fetish than it was in the 1970s

and 1980s. In 2013, the New York Times

reported Ferrari, unhappy about what they regarded as fakes being traded, were

going to try to pressure the high-end auction houses not to host such sales but the industry persists and there are a

number of replica 275 NARTs although, not all were based on a twin-cam original,

industry sources suggesting a premium above a berlinetta of 20% at most. Other popular candidates for conversion

include the Mercedes-Benz 280 SE 3.5 Coupés (1968-1971; on which an exact

conversion is also very challenging), Maserati Ghiblis (1967-1973) and the early

Jaguar E-Types, technically a simpler job especially in years gone by when suitable cars were both cheaper and more numerous.

1976 Ferrari 365 GTB/4 NART by Michelotti

In a

footnote to the Daytona’s history, either not discouraged by his experience with

the 275 NART or impressed by the prices the ten were commanding, Luigi Chinetti

commissioned the construction of five 365 GTB/4 Daytona NART Spiders, the

design turned over to Giovanni Michelotti (1921–1980). In the spirit of 1950s minimalism, Michelotti’s

first design, shown at the 1974 Turin Motor Show featured cut-down doors and a

removable targa top but the second, built for the 1975 24 Hours of Le Mans, was

more a conventional race-car, its lines attuned to aerodynamic enhancement

although it never made the event because of a dispute with the notoriously

difficult stewards. Still interested in

the concept however, in 1976 Chinetti ordered three more NART Daytonas from

Michelotti, configured this time as road-cars with air conditioning and electric

windows, the target market the US. Unlike

the 275 NARTs, the three NART Daytonas really were used cars, production of the

originals having ceased in 1973. One of

them has been a fixture on the show and auction scene for a while, Michelotti using

it as a display piece and it spent two years as an exhibit at the Le Mans

Museum before bouncing around the premium auction circuit where it’s exchanged

between collectors at increasingly higher prices. The wedge shape certainly marks the design as a product of the age but so did the detailing: instead of a delicate cloisonné on the tail, NART was printed in big, bold, upper-case letters.