Futurism (pronounced fyoo-chuh-riz-uhm)

(1) A movement

in avant-garde art, developed originally by a group of Italian artists in 1909 in

which forms (derived often from the then novel cubism) were used to represent

rapid movement and dynamic motion (sometimes

with initial capital letter)

(2) A

style of art, literature, music, etc and a theory of art and life in which

violence, power, speed, mechanization or machines, and hostility to the past or

to traditional forms of expression were advocated or portrayed (often with initial

capital letter).

(3) As futurology,

a quasi-discipline practiced by (often self-described) futurologists who

attempt to predict future events, movements, technologies etc.

(4) In

the theology of Judaism, the Jewish expectation of the messiah in the future

rather than recognizing him in the presence of Christ.

(5) In

the theology of Christianity, eschatological interpretations associating some

Biblical prophecies with future events yet to be fulfilled, including the

Second Coming.

1909: From

the Italian futurismo (literally "futurism" and dating from circa 1909), the construct being futur(e) + -ism. Future was from the Middle English future & futur, from the Old French futur,

(that which is to come; the time ahead) from the Latin futūrus, (going to be; yet to be) which (as a noun) was the irregular

suppletive future participle of esse (to

be) from the primitive Indo-European bheue

(to be, exist; grow). It was cognate

with the Old English bēo (I become, I

will be, I am) and displaced the native Old English tōweard and the Middle English afterhede (future (literally

“afterhood”) in the given sense. The

technical use in grammar (of tense) dates from the 1520s. The –ism suffix was from the Ancient Greek

ισμός (ismós) & -isma noun suffixes, often directly,

sometimes through the Latin –ismus

& isma (from where English picked

up ize) and sometimes through the French –isme

or the German –ismus, all

ultimately from the Ancient Greek (where it tended more specifically to express

a finished act or thing done). It

appeared in loanwords from Greek, where it was used to form abstract nouns of

action, state, condition or doctrine from verbs and on this model, was used as

a productive suffix in the formation of nouns denoting action or practice,

state or condition, principles, doctrines, a usage or characteristic, devotion

or adherence (criticism; barbarism; Darwinism; despotism; plagiarism; realism;

witticism etc). Futurism,

futurology, & futurology are nouns, futurist is a noun & adjective and futuristic

is an adjective; the noun plural is futurisms.

As a descriptor of the movement in art and literature, futurism (as the Italian futurismo) was adopted in 1909 by the Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876-1944) and the first reference to futurist (a practitioner in the field of futurism) dates from 1911 although the word had been used as early as 1842 in Protestant theology in the sense of “one who holds that nearly the whole of the Book of Revelations refers principally to events yet to come”. The secular world did being to use futurist to describe "one who has (positive) feelings about the future" in 1846 but for the remainder of the century, use was apparently rare. The (now probably extinct) noun futurity was from the early seventeenth century. The noun futurology was introduced by Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) in his book Science, Liberty and Peace (1946) and has (for better or worse), created a minor industry of (often self-described) futurologists. In theology, the adjective futuristic came into use in 1856 with reference to prophecy but use soon faded. In concert with futurism, by 1915 it referred in art to “avant-garde; ultra-modern” while by 1921 it was separated from the exclusive attachment to art and meant also “pertaining to the future, predicted to be in the future”, the use in this context spiking rapidly after World War II (1939-1945) when technological developments in fields such as ballistics, jet aircraft, space exploration, electronics, nuclear physics etc stimulated interest in such progress.

Futures, a financial instrument used in the trade of currencies and commodities appeared first in 1880; they allow (1) speculators to bet on price movements and (2) producers and sellers to hedge against price movements and in both cases profits (and losses) can be booked against movement up or down. Futures trading can be lucrative but is also risky, those who win gaining from those who lose and those in the markets are usually professionals. The story behind crooked Hillary Clinton's extraordinary profits in cattle futures (not a field in which she’d previously (or has subsequently) displayed interest or expertise) while “serving” as First Lady of Arkansas ((1979–1981 & 1983–1992) remains murky but it can certainly be said that for an apparently “amateur” dabbling in a market played usually by experienced professionals, she was remarkably successful and while perhaps there was some luck involved, her trading record was such it’s a wonder she didn’t take it up as a career. While many analysts have, based on what documents are available, commented on crooked Hillary’s somewhat improbable (and apparently sometime “irregular”) foray into cattle futures, there was never an “official governmental investigation” by an independent authority and no thus adverse findings have ever been published.

Given what would

unfold over during the twentieth century, it’s probably difficult to appreciate

quite how optimistic was the Western world in the years leading up to the World

War I (1914-1918). Such had been the rapidity of the

discovery of novelties and of progress in so many fields that expectations of

the future were high and, beginning in Italy, futurism was a movement devoted

to displaying the energy, dynamism and power of machines and the vitality and

change they were bringing to society. It’s

also often forgotten that when the first futurist exhibition was staged in

Paris in 1912, the critical establishment was unimpressed, the elaborate imagery

with its opulence of color offending their sense of refinement, now so attuned

to the sparseness of the cubists.

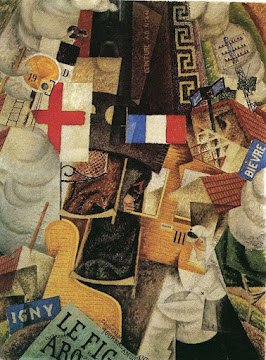

Futurism had debuted with some impact, the Paris newspaper Le Figaro in 1909 publishing the manifesto by Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Marinetti which dismissed all that was old and celebrated change, originality, and innovation in culture and society, something which should be depicted in art, music and literature. Marinetti exalted in the speed, power of new technologies which were disrupting society, automobiles, aeroplanes and other clattering machines. Whether he found beauty in the machines or the violence and conflict they delivered was something he left his readers to decide and there were those seduced by both but his stated goal was the repudiation of traditional values and the destruction of cultural institutions such as museums and libraries. Whether this was intended as a revolutionary roadmap or just a provocation to inspire anger and controversy is something historians have debated. Assessment of Marinetti as a poet has always been colored by his reputation as a proto-fascist and some treat as "fake mysticism" his claim his "visions" of the future and the path to follow to get there came to him in the moment of a violent car crash.

As a technique, the futurist artists borrowed much from the cubists, deploying the same fragmented and intersecting plane surfaces and outlines to render a number of simultaneous, overlaid views of an object but whereas the cubists tended to still life, portraiture and other, usually static, studies of the human form, the futurists worshiped movement, their overlays a device to depict rhythmic spatial repetitions of an object’s outlines during movement. People did appear in futurist works but usually they weren’t the focal point, instead appearing only in relation to some speeding or noisy machine. Some of the most prolific of the futurist artists were killed in World War I and as a political movement it didn’t survive the conflict, the industrial war dulling the public appetite for the cult of the machine. However, the influence of the compositional techniques continued in the 1920s and contributed to art deco which, in more elegant form, would integrate the new world of machines and mass-production into motifs still in use today.

The Modern Boy (1928-1939) was, as the name implies, a British magazine targeted at males aged 12-18 and the content reflected the state of mind in the society of the inter-war years, the 1930s a curious decade of progress, regression, hope and despair. Although what filled much of the pages (guns, military conquest and other exploits, fast cars and motorcycles, stuff the British were doing in other peoples’ countries) would today see the editors cancelled or visited by one of the many organs of the British state concerned with the suppression of such things), it was what readers (presumably with the acquiescence of their parents) wanted. Best remembered of the authors whose works appeared in The Modern Boy was Captain W.E. Johns (1893–1968), a World War I RFC (Royal Flying Corps) pilot who created the fictional air-adventurer Biggles. The first Biggles tale appeared in 1928 in Popular Flying magazine (released also as Popular Aviation and still in publication as Flying) and his stories are still sometimes re-printed (although with the blatant racism edited out). The first Biggles story had a very modern-sounding title: The White Fokker. The Modern Boy was a successful weekly which in 1988 was re-launched as Modern Boy, the reason for the change not known although dropping superfluous words (and much else) was a feature of modernism. In October 1939, a few weeks after the outbreak of World War II, publication ceased, Modern Boy like many titles a victim of restrictions by the Board of Trade on the supply of paper for civilian use.

If the characteristics of futurism in art were identifiable (though not always admired), in architecture, it can be hard to tell where modernism ends and futurism begins. Aesthetics aside, the core purpose of modernism was of course its utilitarian value and that did tend to dictate the austerity, straight lines and crisp geometry that evolved into mid-century minimalism so modernism, in its pure form, should probably be thought of as a style without an ulterior motive. Futurist architecture however carried the agenda which in its earliest days borrowed from the futurist artists in that it was an assault on the past but later moved on and in the twenty-first century, the futurist architects seem now to be interested above all in the possibilities offered by advances in structural engineering, functionality sacrificed if need be just to demonstrate that something new can be done. That's doubtless of great interest at awards dinners where architects give prizes to each other for this and that but has produced an international consensus that it's better to draw something new than something elegant. The critique is that while modernism once offered “less is more”, with neo-futurist architecture it's now “less is bore”. Art deco and mid-century modernism have aged well and it will be interesting to see how history judges the neo-futurists.