Kink (pronounced kingk)

(1) A

twist or curl, as in a thread, rope, wire, or hair, caused by its doubling or

bending upon itself.

(2) An

expression describing muscular stiffness or soreness, as in the neck or back.

(3) A

flaw or imperfection likely to hinder the successful operation of something, as

a machine or plan (differs from a bug in that kinks or their consequences tend

immediately to be obvious.

(4) A

mental twist; notion; whim or crotchet (and in a pejorative sense an

unreasonable notion; a crotchet; a whim; a caprice).

(5) In

slang, a flaw or idiosyncrasy of personality; a quirk.

(6) In

slang, bizarre or unconventional sexual preferences or behavior; a sexual

deviation (Defined as paraphilia; the parameters of paraphilic disorders (essentially

that which is non-normophilic) are (to some extent) defined in the American

Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and

Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) but the public perception of

kinkiness varies greatly between and within cultures).

(7) In

slang, a person characterized by such preferences or behavior (a kinkster).

(8) To

form, or cause to form, a kink or kinks, as a rope or hairstyle or a physical

construction like a road; to be formed into a kink or twist.

(9)

Loudly to laugh; to gasp for breath as in a severe fit of coughing (now rare

except in Scotland).

(10) In

mathematics, a positive 1-soliton solution to the sine-Gordon equation.

(11) In

the jargon of US railroad maintenance as “sun kink”, a buckle in railroad track

caused by extremely hot weather, which could cause a derailment.

(12) In

fandom slang as “kinkmeme” (or kink meme), an online space in which requests

for fan fiction (generally involving a specific kink) are posted and fulfilled

anonymously (a subset thus of the anon meme).

(13) In

slang, as “kinkshame” (or kink-shame or kink shame), to mock, shame, or condemn

someone (a kinker) for their sexual preferences or interests and fetishes.

1670–1680:

From the Middle English kink (knot-like

contraction or short twist in a rope, thread, hair, etc (originally a nautical

term), from the Dutch kink (a twist

or curl in a rope), from the Proto-Germanic kenk-

& keng- (to bend, turn), from the

primitive Indo-European geng- (to turn, wind, braid, weave) and related to the

Middle Low German kinke (spiral

screw, coil), the Old Norse kikna (to

nod; to bend backwards, to sink at the knee as if under a burden”) and the , the

Icelandic kengur (a bend or

bight; a metal crook). It’s thought

related to the modern kick although a LCA (last common ancestor) has never been

identified. The intransitive verb

emerged in the 1690s and the transitive by the early nineteenth century. The adjective kinky (at that stage of

physical objects such as ropes or hair full of kinks, twisted, curly) seems

first to have been used in 1844. Words

with a similar meaning (depending on context) include crimp, wrinkle, flaw,

hitch, imperfection, quirk, coil, corkscrew, crinkle, curl, curve,

entanglement, frizz, knot, loop, tangle, cramp, crick, pain &, pang The sense familiar in Scottish dialect use (a

convulsive fit of coughing or laughter; a sonorous in-draft of breath; a whoop;

a gasp of breath caused by laughing, coughing, or crying) was from the From Middle

English kinken & kynken, from the Old English cincian (attested in cincung), from the Proto-West Germanic kinkōn, from the Proto-Germanic kinkōną (to laugh), from the primitive Indo-European

gang- (to mock, jeer, deride), and related to the Old English canc (jeering, scorn, derision). It was cognate with the Dutch kinken (to kink, to cough). One curious adaptation was the (nineteenth

century) use of kinker to describe circus performers, presumably on the basis

of their antics (kinky in the sense of a twisted rope). Kink is a noun & verb, kinkily is an

adverb, kinkiness & kinkster are nouns, kinked is a verb & adjective,

kinky and kinkier & kinkiest are adjectives; the noun plural is kinks.

Kink

appears to have entered English in the 1670 from the interaction of English

& Dutch seafarers, the first use of the word being nautical, French & Swedish

gaining it in a similar manner. The figurative

sense of “an odd notion, a mental twist, a whim, a capricious act” was first

noted in US English in 1803 in the writings of Thomas Jefferson (1743–1826; US

president 1801-1809). It was one of the

many terms applied to those thought “sexually abnormal”, the first use noted in

1965 (although the adjective kinky had been so applied as early as 1959) and

the use as a synonym for “a sexual perversion, fetish, paraphilia” is thought

by most etymologists to have become established by the early 1970s. The slang, “kinkshame” means “to mock, shame,

or condemn someone (a kinker) for their sexual preferences or interests and

fetishes”. Dictionaries tend to list

this only as a verb (ie that directed at another) but it would seem also a noun

(a feeling of kinkshame), such as that suffered by Umberto Nicola Tommaso

Giovanni Maria di Savoia (1904–1983; the last King of Italy (May-June 1946)

who, while heir to the throne (and styled Prince of Piedmont), Benito Mussolini’s

(1883-1945; Duce (leader) & prime-minister of Italy 1922-1943) secret

police discovered the prince was a sincere and committed Roman Catholic but one

unable to resist his “satanic homosexual

urges” and his biographer agreed, noting he was “forever rushing between chapel and brothel, confessional and steam bath”

often spending hours “praying for divine

forgiveness.” He would seem to have

been suffering kinkshame.

Lindsay Lohan with kinked hair.

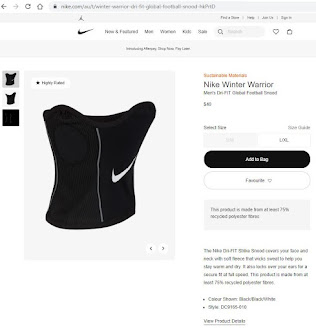

Car & Driver "Fastest American Car" comparison test, April 1976.Although

the word kinky had by then for some time been in use to describe sexual

proclivities beyond the conventional, in April 1976, when the US magazine Car & Driver chose to describe a

pickup truck as “kinky” it was using the word in the sense of “quirky” or “different” and certainly not in a pejorative way. While testing the Chevrolet C-10 stepside in

an attempt to find the fastest American built “car”, the editors noted that

although the phenomenon hadn’t yet travelled south of the Mason-Dixon Line. “…kinky pickups are one of the more recent

West Coast fascinations”. A few years

earlier, it would have been absurd to include a pickup in a top-speed contest but

the universe had shifted and ownership of the fast machines of the pre-1972 muscle

car era had been rendered unviable by the insurance industry before being

banned by the legislators; by earlier standards, high-performance was no longer

high. Some demand for speed however

remained and General Motors found a loophole: the Environmental Protection Agency

(EPA) didn't impose power-sapping exhaust emission controls on anything with a gross

vehicle weight rating above 6000 pounds (2722 kg). Thus emerged Chevrolet’s combination of the heavy-duty

version of the pickup chassis (F44) with the big-block, 454 cubic inch (7.4 litre) V8,

a detuned edition of the engine which half-a-decade earlier had been offered with the

highest horsepower rating Detroit had ever advertised. Power and brutish enjoyment was ensured but the

aerodynamic qualities of the pickup were such it could manage only third place

in Car & Driver’s comparison, its 110 (177 km/h) mph terminal velocity shaded by the

Pontiac Trans Am (118/190) and the Chevrolet Corvette (125/201) which won although both were slow compared with what recently had been possible.

The pickup did however outrun Ford’s Mustang Mach 1 which certainly

looked the part but on the road prove anaemic, 106 mph (171 km/h) as fast as it could

be persuaded to go. In second place was

what turned out to be the surprise package, the anonymous-looking Dodge Dart which,

although an old design, was powered by a version of the Chrysler LA small-block

V8, one of the best of the era and clean enough to eschew the crippling

catalysts most engines by then required.

Its 122 mph (196 km/h) capability made it the fastest American sedan.

The kinky pickup however

was a harbinger for where went California, so followed the other forty-nine. The idea of the kinky pickup had actually

begun in 1964 when Chrysler quietly slipped onto the market a high-performance version of the the Dodge D-100, a

handful of which were built with a 413 (6.7 litre) cubic inch V8 but with

little more fanfare, the 426 cubic inch (7.0 litre) Street Wedge was next year added to

the option list which, rated at 365 horsepower, was more than twice as powerful

than the competition. Ahead of its time,

the big-power in the engines D-100 were withdrawn in 1966 but it was the first muscle

truck and the spiritual ancestor of the C-10 which a decade later was faster

than the hottest Mustang, damning with faint praise though that may be. The trend continued and Dodge early in the

twenty-first century even sold pickups with an 8.3 litre (505 cubic inch) V10. The market has since shown little sign of

losing its desire for fast pickups and the new generation of electric vehicles

are likely to be faster still.

The adjective "kinky" evolved from the noun but a linguistic quirk in the use of "kink" in the gay community is that etymologically it was technically a back-formation from "kinky". In the LGBTQQIAAOP

movement, there is some debate whether displays of “kink” should be part of “pride”

events such as public parade. One faction

thinks group rights trumps all else and there can be no acceptance of any

restrictions whereas others think the PR cost too high. One implication of some representation of this

or that kink being included in pride parades is that presumably, once accepted as

a part of public displays, it ceases to be kinky and becomes just another place

on the spectrum of normality. Kinky

stuff surely should be what goes on only behind closed doors; if in public it can even be hinted at, it can't truly be a kink because a kink must be something seriously twisted.

1962

BMW 1500 (Neue Klasse, left), the incomparable BMW E9 (1968-1975, centre) and

the 2023 BMW 760i (G70, right).

In

automotive design, the “Hoffmeister kink” is a description of the forward bend

in the C-pillar (D-pillar on SUVs) and it’s associated almost exclusively with BMW (Bayerische

Motoren Werke) vehicles built since the early 1960s. The kink is named after Wilhelm Hofmeister

(1912–1978; BMW design chief 1955-1970) who used the shape on the BMW Neue

Klasse (The “New Class”, the first of which was the 1500 and in various

forms was in production 1962-1975) although the BMW 3200 CS (1962-1965) which

was styled by Giuseppe "Nuccio" Bertone (1914–1997) also used the

lines and design work of both began in 1960.

However, the name “Hoffmeister kink” stuck not because it originated

with Herr Hoffmeister but because BMW has for decades stuck with it so it’s now

perhaps even more of an identifiable motif than their double-kidney grill which

is now less recognizable than once it was.

Herr Hoffmeister deserves to be remembered because the work of his

successors has been notably less impressive and none has matched his E9 coupe

(1968-1975) although it gained as much infamy for its propensity to rust as

admiration for its elegance.

Some of

the pre-Hoffmeister kinks: 1949 Buick

Super Sedanette (left), 1951 Kaiser Deluxe (centre) and 1958 Lancia Flaminia

Sport Zagato (right).